Vernacular Inclusion to Sustainable Urbanisation

Cette étude examine comment des solutions de conception résilientes et adaptatives, solidement ancrées dans les systèmes de connaissances vernaculaires, peuvent être adaptées aux établissements formels à travers l'Afrique. Le continent incarne des systèmes qui soutiennent les communautés depuis des siècles, englobant la santé, l'éducation, la religion, la culture, les transports et la gouvernance. Ces groupes, qui sont souvent exclus du processus de développement urbain traditionnel, s'adaptent socialement et géographiquement aux contraintes économiques, culturelles et environnementales. Cette recherche utilise des études de cas provenant des États de Lagos, d'Osun et de Kaduna au Nigeria pour redéfinir les quartiers informels comme des écosystèmes créatifs et ingénieux plutôt que comme des échecs urbains. Elle soutient que pour créer des paradigmes de conception inclusifs, adaptés au climat et culturellement pertinents, les urbanistes et les architectes africains doivent s'inspirer de ce type d'habitats. Cette idéologie s'inscrit dans un mouvement plus large visant à soutenir les solutions urbaines africaines et à décoloniser la pensée spatiale.

This study examines how resilient, responsive design solutions with a strong foundation in vernacular knowledge systems can be adapted into formal settlements across Africa. The continent embodies systems that have sustained communities for centuries, encompassing health, education, religion, culture, transportation, and governance. These groups, which are frequently left out of the mainstream urban development process, adjust socially and geographically to economic, cultural, and environmental constraints. This research uses case studies from Lagos, Osun, and Kaduna States in Nigeria to redefine informal settlements as creative and resourceful ecosystems rather than as urban failures. It makes the case that in order to create inclusive, climate-responsive, and culturally relevant design paradigms, African landscape planners and architects need to learn from this type of settlement. This philosophy is in line with a larger movement to support African-led urban solutions and decolonize spatial thinking.

Introduction

The African continent is seeing significant urbanisation (UN-Habitat, 2022). Much of this growth occurs in informal settlements, which are often unplanned, underserved, and misunderstood. Yet, these settlements contain a wealth of indigenous knowledge, vernacular traditions, and adaptable spatial tactics (Myers, 2021).

organisational

Informal settlements are quite adaptive and resilient forms of human settlements, suggesting they are products of a vernacular approach to design. They are not guided by architectural trends or planning codes but are rather borne out of necessity, tradition, and environmental resilience (AlSayyad, 2004).

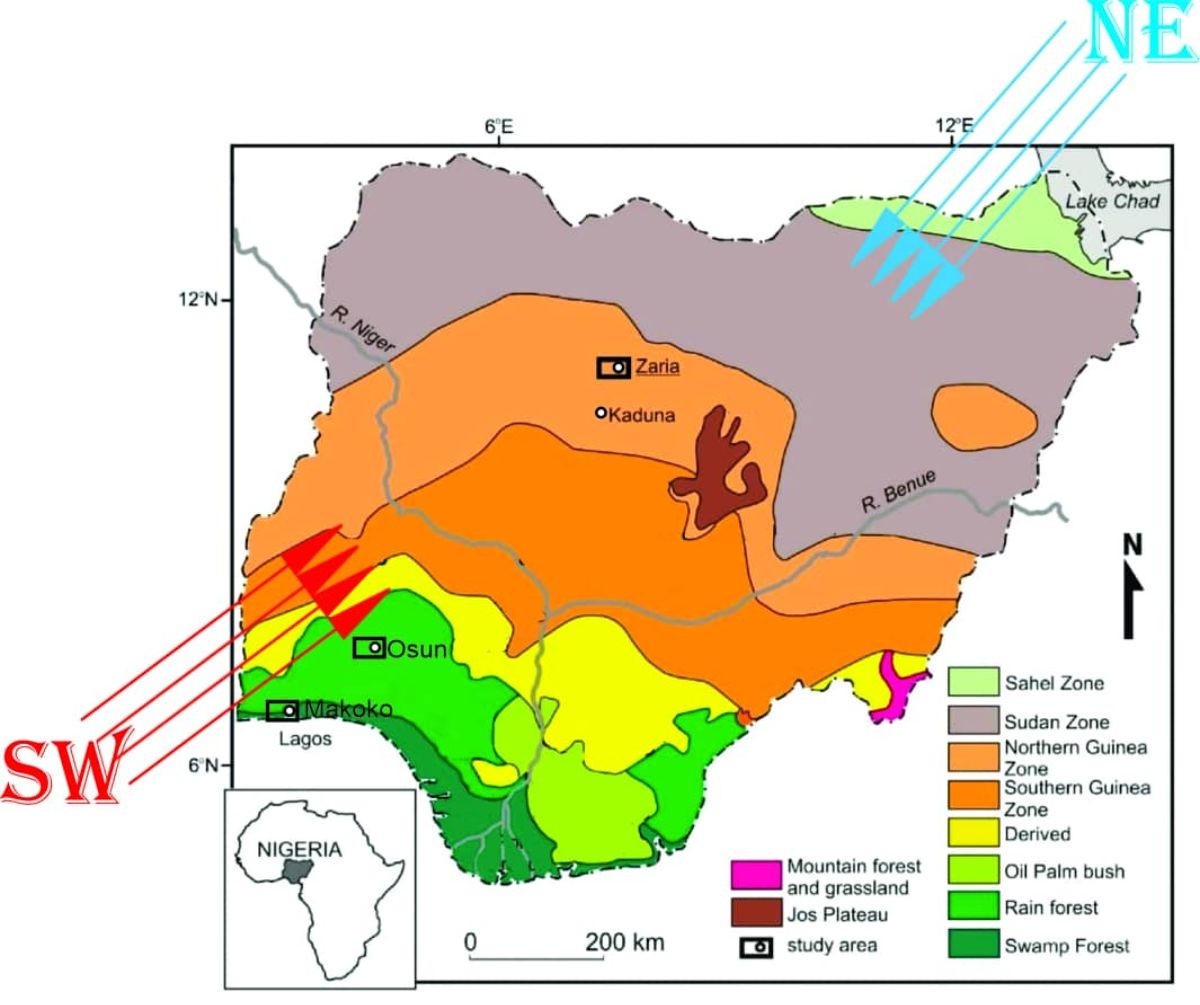

Nigeria has both the rainy and dry seasons, driven by monsoon winds. The north easterly winds blow sand from the Sahara Desert, laden with Harmattan dust, while the south westerly winds bring water from the Atlantic Ocean causing the rainy season. The coastal region features mangrove forests, freshwater swamps and beaches. It spans Lagos, Delta, Rivers, Cross River, Bayelsa States, etc. They experience high rainfall and humidity (Areola, 1982). The rain forest region consists of tropical thick wood forest and crops such as cocoa, oil palm, bamboo, Iroko, mahogany, palm trees, etc. It covers states like Ondo, Osun, Edo, and Ogun. They experience high rainfall, and the soil is fertile and supports biodiversity (Ayoade, 1983). The Savannah, otherwise known as grasslands, is divided into three zones. Namely, Guinea, Sudan, and Sahel (Fig. I). The Guinea savannah is covered with trees, although the trees become sparse northwards. The Sahel is a semi-arid region. (Kurowska, 2022). For this research, the focus is limited to the swamp forest, rainforest, and the savannah landscape environments where the three case studies and settlements are located.

Aim & Objectives

This study aims to investigate certain Nigerian vernacular landscapes for an adaptation into responsive design principles, which can be beneficial to contemporary architectural urban practice.

The objectives are to:

1. Assess the resilience and spatial organization of Makoko as an informal settlement.

2. Examine the cultural impact of the Osun Sacred Grove on the environment.

3. Highlight climate-responsive strategies in the Zaria savannah vernacular architecture.

4. Derive lessons complimentary to contemporary responsive design frameworks.

Scope of Study

This study covers how vernacular knowledge systems and informal settlements help to shape sustainable and responsive landscapes. It will be limited to 3 case studies, namely Makoko (Lagos) in the swampy rain forest, Osun grove in the tropical rain forest, and Kaduna State which is within the Savannah Landscape. The focus of this research is to highlight lessons that can inform contemporary urban sustainability models.

Literature review

Vernacular knowledge, resilience, and responsive design

The study of vernacular architecture and landscape practices as adaptive systems makes use of local materials that are climate responsive. They exist in a social organisational context with strong cultural meaning (Oliver, 2006). Fathy (2010) suggests that vernacular relies on locally based strategies for thermal comfort, material efficiency, and social cohesion. These are qualities that are also desirable in a contemporary and sustainable design.

Vernacular systems should be considered beyond artefacts; rather, they are containers of active local knowledge systems in which materials, forms, and community practices adapt to the environmental constraints (Oliver, 2006).

Resilience theory is a conceptual bridge that connects vernacular practice and structured sustainability thinking. The idea of resilience can be used to align the management objectives and procedures for landscape change from the perspective of systems theory. Resilience is defined here as a system's ability to withstand shocks while maintaining essentially the same function, structure, feedback, and hence identity. To put it another way, resilience is the capacity to handle disruptions or change without compromising the fundamental properties of the system (Tobias 2012). Resilience studies focus on the ability to adapt, social-ecological feedback, and the ability of systems to sustain functionality while absorbing shocks (Folke, 2006; Walker et al., 2004). These characteristics or strengths in formal planning language are frequently demonstrated by vernacular settlements through progressive development, flexible tenure arrangements, and communal resource management.

Informal settlements as adaptive/innovative landscapes: Makoko and comparable studies

Informal settlements are considered problems to be eradicated when making policies (Folke, 2006) (Walker, 2004). Most studies reframe them as repositories of adaptive solutions. Various literature about Lagos and other coastal communities talk about how locals develop amphibious coping strategies like stilt housing, raised platforms, innovative drainage methods, social interaction, and networking for rapid recovery, which helps to reduce frequent risk in the absence of formal infrastructure (Adelekan, 2011; Olanrewaju et al., 2019). Makoko is an emblematic informal water-based settlement that has been compared to the Italian city of Venice. The residents of Makoko have adapted their housing and transportation to tidal conditions and poor municipal services. If combined with improved sanitation, better ownership rights, and support in engineering, this kind of adaptation may present opportunities for amphibious or floating design typologies (UN-Habitat; Adelekan, 2011).

The literature also addresses challenges. These range from environmental health risks, poor sanitation, structural fragility, insecure tenure/ownership, and development control activities such as demolition, which causes displacement along with homelessness, disruption of livelihood, violence, etc. (Agbola, 1990; Adegun, 2017). Reclamation of water to land by sand filling in proximity to the settlement is also threatening the existence of Makoko. The socio-economic reality is that the locals cannot afford the sand-filled plots (Fig. 2). Furthermore, these plots directly affect its hydrology, and this comes with different issues such as floods, a rise in water levels, etc. This dual nature of ingenuity and fragility has made Makoko an important test case for integrating vernacular adaptation into formal resilience planning (Gbadebo, 2025).

Sacred and cultural landscapes as conservation mechanisms: Osun Sacred Grove

Spiritual places such as sacred groves, cursed, haunted, enchanted forests, and other culturally protected landscapes are great examples of how traditional institutions can help with ecosystem conservation.

The Osun Sacred Grove exemplifies ritual stewardship and cultural taboos (Fig. 3) that allow biodiversity to be maintained and protects riparian buffers, which can serve as storage for excess carbon around urbanised spaces (UNESCO; Onaiyekan, 2018). IUCN and other literature on sacred landscapes suggest that cultural values can be integrated into conservation and Nature-Based Solution (NbS) agendas, because local laws can serve to protect ecological functions where government regulations may be weak (IUCN, 2012).

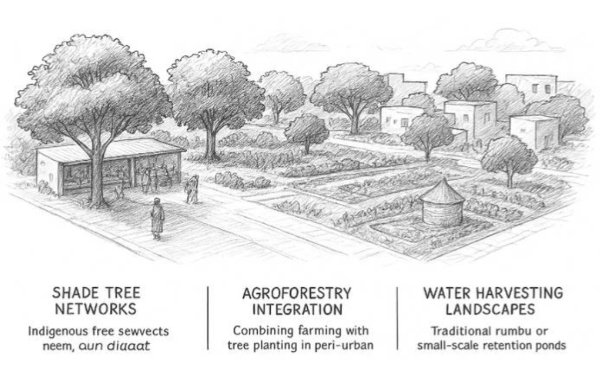

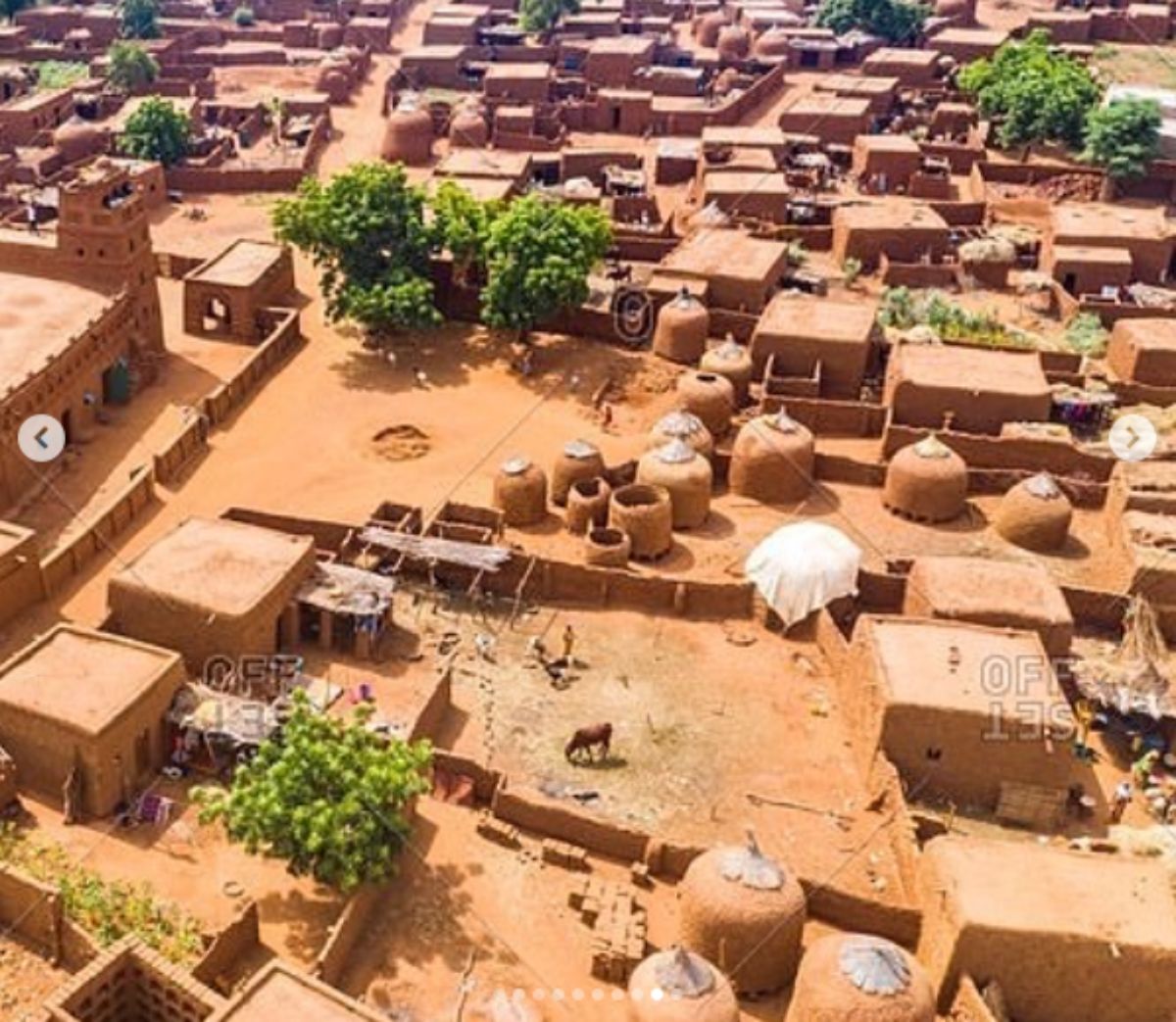

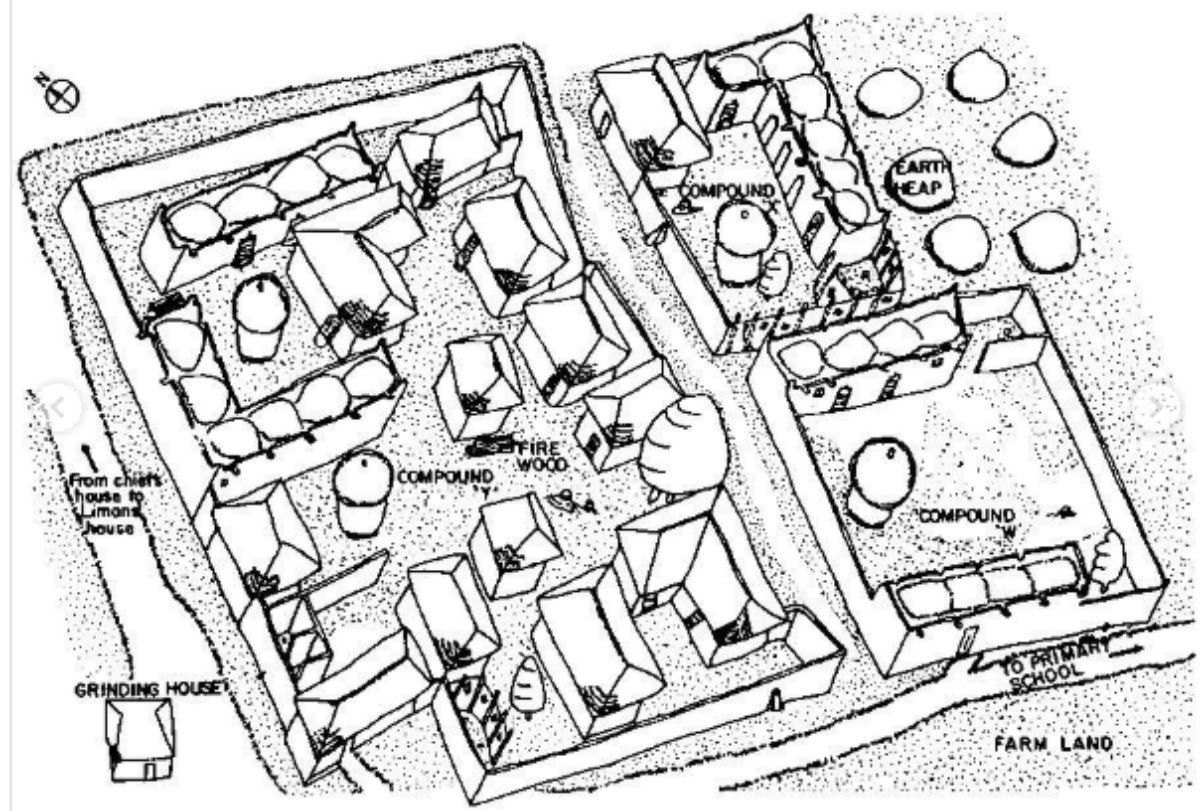

Savannah vernaculars and climatic adaptation: Zaria

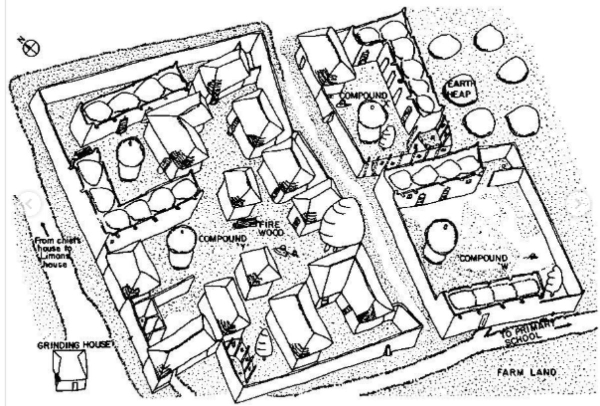

In semi-arid and savannah contexts, traditional architecture makes use of adobe walls, and homes are built around a courtyard. The streets are narrow and shaded by buildings, which achieves thermal comfort and reduces energy consumption through passive design (Olaniyan, 2019). Figure 4 shows a strong character in building design. Water is harvested traditionally, while agroforestry methods practiced in the savannah display how they have used low-tech, locally tuned strategies for water security and erosion control. With increasing calls for climate-sensitive planning, these practices are relevant especially in vulnerable regions where heat stress and rainfall variability are experienced.

The semi-arid climate is harsh. It is hot and dry with dusty winds and scarce rainfall (Abubakar, Musa & Umar, 2021; Olusola, 2018). The culture is shaped by religion (Islam) and the historical Trans-Sahara Trans-Atlantic trade. Natives dress modestly and are fully clad. Gender segregation and polygamy influences design of households. Most compounds are designed to have separate private quarters for the wives, and shared spaces such as the courtyard (Prussin, 1995). Mosque, Qur’anic schools (makaranta), and local markets are central to dwelling design. This shows the level of impact religion has on in the Hausa-Fulani urbanism. (Figs. 5-6)

Formal sustainability models: Sponge cities, Green Infrastructure and Nature-based Solutions (NbS)

There are various contemporary approaches to urban water and climate management. These include the Sponge City Concept, Green Infrastructure, and Nature-based Solutions (NbS). They revolve around similar principles as vernacular practice. Principles such as permeability, retention, multi-functionality, and alignment of social and ecological functions. The Sponge City approach adopted in China utilises urban porosity to incorporate permeable pavements, retention ponds, green roofs, and restored wetlands within an environment to absorb, store, and slowly release stormwater (Li et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2018). Studies on NbS also explain other co-benefits of ecosystem-based interventions in water quality, biodiversity and livelihoods (Cohen-Shacham et al., 2016; Raymond et al., 2017). Green Infrastructure scholarship similarly focuses on the relationship between ecological features and how they regulate climate and perform recreational functions (Benedict, 2002).

These models are considered engineered or policy-driven solutions. Increasingly, they are integrating community engagement, local knowledge, and hybrid governance arrangements (Kabisch et al., 2017). The inclusion of vernacular practice and scientific models creates an opportunity to develop hybrid interventions that combine bottom-up adaptation with top-down intervention of technical expertise and resource allocation.

Comparative insights and gaps in the literature

Comparing studies on vernacular systems and scientific models shows a high level of complimentary ideas. They are both based on permeability, multi-functional, and local stewardship. But gaps still exist. There is limited empirical research that gives direction on how vernacular practices can be fused with formal design frameworks. An example is translating Makoko’s techniques into a regulated style that can culminate in a durable floating housing model capable of meeting sanitation and safety standards. Also, sacred landscapes like Osun grove have been studied more for heritage and tourism value and less as explicit NbS providers (e.g., watershed protection quantified in ecosystem service terms). Another point is that though the sponge city concept offers promising examples, there are very few Africa-specific roadmaps for West African socio-economic development and governance

Positioning this study

This research attempts to bridge existing gaps in the literature by describing vernacular practices in Makoko, Osun and Zaria; comparing them to sponge city, NbS, green infrastructure principles, and proposing a West African context-sensitive design framework that preserves cultural integrity while delivering measurable resilience outcomes. This study aims to produce transferable models for integrating vernacular knowledge into formal resilience planning.

Theoretical framework

Ecological urbanism and resilience are key parts of modern theories of sustainability. Sponge city models rely on urban porosity (Li et al., 2017). According to Benedict and McMahon (2002), green infrastructure relies on developing a network of natural features and systems that sustain biodiversity and control the climate, improving biodiversity and human well-being, while NbS relies on ecosystem-based solutions to help with flooding, food security, and climate change (Cohen-Shacham et al., 2016).

Vernacular practices found in informal settlements often use principles behind sustainable models and practical land-use planning. These illustrations highlight the complementary nature of both paradigms by contrasting top-down scientific frameworks with bottom-up cultural practices.

The idea is to somewhat “decolonise” contemporary urban theories and advance African-led solutions. It does not mean to throw away modern concepts but rather to tailor them to the African context.

This study views vernacular landscapes as "living laboratories" of spatial resilience (Folke, 2006) and adaptive capacity (Walker, 2004). This is demonstrated by the case studies in Nigeria, where Makoko exemplifies survival tactics that are used in water ecosystems in spite of climate danger; Osun Grove combines spirituality and stewardship, while Zaria illustrates ways to adapt to the climate and environment of arid zones. When considered as a whole, they demonstrate how Anthropocene urban sustainability can be improved through local wisdom.

Methodology

The desktop research method is adopted for this case-study approach, which comprises field reports, existing literature, and photographic evidence (Yin, 2018). Comparative analysis is conducted between informal settlements (Makoko) and formal ecological heritage sites (Osun Grove, Zaria Savannah). The study does not involve producing or analysing detailed engineering or hydrological models of the areas. Instead, it is based on cultural and ecological knowledge and how they affect architecture and the landscape. The selected case studies offer various perspectives, yet they do not represent the full diversity of Nigeria’s vernacular landscapes.

Makoko (Water Ecosystems)

Challenges

Sanitation is poor due to insufficient infrastructure (Fig. 7). Waste management and refuse disposal are also challenges. All these leads to smelling and polluted water. (Michael Ajide Oyinloye, 2017)

Lesson

Residents have been able to build their houses using floating and stilted foundations; they have also built their economy around fishing, logging, canoe transportation, and have developed strong communal networks and social interactions to survive urban exclusion and recurrent flooding (Figs. 8-9). Though it is a vulnerable landscape, Makoko illustrates adaptive resilience, and this is a demonstration of necessity driven by innovation.

Importance

Lessons from Makoko contribute to contemporary climate adaptation models by showing how floating architecture, community cohesion, and decentralised livelihoods can inform flood-resilient urban design, especially in coastal megacities facing rising sea levels.

Osun Sacred Grove, Osogbo (Cultural Landscape and Spiritual Ecology)

The Osun Sacred Grove is a UNESCO World Heritage Site (Fig. 10). It is a practical signpost that points to how cultural and ecological knowledge can be found inside Yoruba traditions. The grove embodies the spiritual belief systems that address ecological stewardship in a way that sacredness is a protective mechanism for biodiversity conservation (Olupona, 2011).

Challenges

Urbanisation is gradually encroaching (Figure XIV), and tourism activities threaten the ecological integrity and spiritual sanctity of the Grove because it is not regulated. Inadequate enforcement of conservation laws leaves the site vulnerable to pollution, deforestation, and cultural erosion.

Sacred spaces can be seen to perform the same function as conservation zones. They protect forests, wetlands, and vulnerable species from over exploitation.

Maintaining cultural values in contemporary sustainable planning can provide a model where landscapes are preserved as a cultural identity while offering ecological services.

_12.jpg)

In contrast to purely scientific approaches to sustainability, the grove demonstrates how vernacular systems build resilience through cultural continuity and community-based conservation practices, which can efficiently enhance urbanization.

Zaria Savannah Landscape (Climate Adaptation in Semi-Arid Contexts)

The Zaria savannah exemplifies vernacular adaptation to semi-arid climatic conditions, where communities (Fig. 12) have historically designed housing, farms, and settlements to optimize water, soil, and vegetation use (Mortimore, 2009).

Challenges

The growing challenges of urbanization have given rise to several educational institutions, thereby putting pressure on spatial demands, leading to encroachment on farmland. Similarly, poor agricultural practices such as overgrazing have led to desertification and land degradation.

Lesson

The use of indigenous building materials such as mud walls, thatch, laterite floors as well as adaptive spatial layouts (courtyards, ventilation strategies) help to reduce energy demands while improving thermal comfort. Local farming systems integrate agroforestry and seasonal water management, contributing to both food security and environmental balance. (Figure 13)

Importance

This provides insights for modern sponge-city and green infrastructure concepts, particularly in how communities naturally manage water cycles and microclimates without extensive technology.

Result from the case study

Across the three case studies, vernacular practices demonstrate that responsive design is not only technological but deeply cultural, ecological, and social. Makoko represents adaptive innovation in precarious urban ecologies. The Osun Sacred Grove emphasizes conservation through spirituality. The Zaria Savannah showcases climate-responsive materials and land use. Together, they illustrate that vernacular knowledge systems can complement scientific sustainability frameworks (sponge cities, NbS , green infrastructure) by grounding resilience in lived experience, cultural values, and community practices.

Conclusion

If African cities are to reshape for the future, there is a need to discard the desire to adopt design, planning, and sustainability models without tailoring them to suit our environment.

Wholesale importation of Western urban models, though desirable, should rather be customized to conform to local peculiarities. Design should be cultural, ecological, and environmentally responsive for sustainable growth and development.

Informal communities, which are stigmatized and called slums, can be integrated within formal sustainable models. The challenge, therefore, is not to erase or displace these systems but to learn from them. This is how elevating vernacular knowledge becomes a legitimate counterpart to scientific expertise.

Toward a New Design Ethos

Reshaping the African cities for the future, designers and policy makers will need to combine the values of informal settlements by:

1. Integrating vernacular principles into design education, creating future professionals who value indigenous ideas and practices.

2. Encouraging a participatory design process, engaging local communities in making decisions.

3. Advocating for flexible regulations that accommodate the various social and economic classes of people. This could help make development affordable while integrating a mechanism to ensure public health and safety

4. Recognising landscape architects as facilitators in the process of bridging environmental, cultural, and social dynamics within urban spaces. Landscape architects are able to design visual plans that integrate various submissions from other professionals.

References

Abubakar, A. M.., (2021. A Study of Vernacular Architecture in Relation to Sustainability: The Case of Northern Nigeria. Near East University Journal of Faculty of Architecture (NEUJFA), 10(2), p. 75–85.

Adelekan, I. O., 2011. Vulnerability of poor urban coastal communities to climate change in Lagos, Nigeria. Environment & Urbanization, 23(1), p. 261–281.

Agbola, T., 1990. Maroko: Urban squalor and government response in Lagos. Third World Planning Review, 12(1), p. 1–22.

AlSayyad, N., 2004. Forms of dominance: On the architecture and urbanism of the colonial enterprise. Avebury: Brooksfield USA.

Areola, O., 1982. Vegetation of Nigeria. In: Barbour, K.M., Oguntoyinbo, J.S., Onyemelukwe, J.O. & Nwafor, J.C. (eds.) Nigeria in Maps. London. Hodder and Stoughton, p. pp. 113–115.

Ayoade, J., 1983. Introduction to Climatology for the Tropics. Ibadan: Spectrum Books.

Benedict, M. A., 2002. Green Infrastructure: Smart Conservation for the 21st Century. s.l.: Sprawl Watch Clearinghouse.

Chan, F. K. 2018. “Sponge City” in China - A breakthrough of planning and flood risk management in the urban context. Land Use Policy, Volume 76, p. 772–778.

Cohen-Shacham, E. W.., 2016. Nature-based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges, s.l.: IUCN.

Folke, C, 2006. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), p. 253–267.

Gbadebo, R. V., 2025. Makoko: Haphazard Sandfilling the Prime Cause of Flooding in Lagos State - Rhodes-Vivour [Interview] (16 February 2025).

Huchzermeyer, M., 2011. Cities with 'slums': From informal settlement eradication to a right to the city in Africa. Cape town: UCT Press.

IUCN, 2012. The IUCN Programme 2013–2016: Valuing and conserving nature, enhancing livelihoods, and equitable governance of natural resources. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Kurowska, E. C. 2022. Afforestation of transformed savanna and resulting land cover change: A case study of Zaria (Nigeria). Sustainability, 14(3), p. 1160.

Li, H. D. 2017. Sponge City Construction in China: A Survey of the Challenges and Opportunities. Water, 9(9), p. 594.

Mbembe, A. 2004. Writing the World from an African Metropolis. Public Culture, 16(3), p. 347–372.

Michael Ajide Oyinloye, I. O., 2017. Urban renewal strategies in developing nations: A focus on Makoko, Lagos State, Nigeria. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, pp. 229-241.

Mortimore, M., 2009. Dryland Opportunities: A new paradigm for people, ecosystems and development. Gland, Switzerland, London and New York.: IUCN, IIED and UNDP.

Myers, G., 2021. Rethinking urbanism: Lessons from postcolonialism and the Global South. Bristol: University Press.

Olaniyan, O., 2019. Vernacular responses to climate in Hausa architecture. Journal of Architecture and Environment, 18(2), p. 55–68.

Oliver, P., 2006. Built to meet needs: Cultural issues in vernacular architecture. Milton Park, Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Olupona, J., 2011. City of 201 Gods: Ile-Ife in Time, Space and Imagination. California: University of California Press.

Olusola, O., 2018. A Lesson from Vernacular Architecture in Nigeria. Journal of Architecture and Built Environment, 5(3), p. 45–54.

Prussin, L., 1995. Hatumere: Islamic Design in West Africa. Calfornia: University of California Press.

Raymond, C. M., 2017. A framework for assessing and implementing the co-benefits of nature-based solutions. Environmental Science & Policy, Volume 77, p. 15–24.

Tobias P.2012. Resilience and the Cultural Landscape: Understanding and Managing Change. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Turner, J. F. , 1976. Housing by People: Towards Autonomy in Building Environments. London: Marion Boyars.

UN-Habitat, 2022. World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme., Nairobi: United Nations.

Walker, B. H.., 2004. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2).

Yin, R. K. 2018. Case study research and application: Design and methods. 6th ed. s.l.: Sage Publications.

Yu, K., 2015. Sponge cities: Ecological infrastructure for water management. Engineering, 1(3), p. 291–298.