Eerste Tol: A Cultural Landscape Approach to Development

L'étude de cas Eerste Tol illustre une approche du patrimoine fondée sur le paysage qui évalue et oriente le développement. L'étude met également l'accent sur une perspective de paysage culturel alignée sur le cadre de l'UNESCO et de l'ICOMOS, prônant une relation étroite entre la nature et les établissements humains. Bien que le site du patrimoine mondial dans lequel se trouve le village d'Eerste Tol soit classé pour ses propriétés naturelles, Eerste Tol lui-même est considéré comme un site culturel dans ce contexte. C'est donc dans cette perspective que les auteurs du document commentent la proposition de développement.

Le hameau d'Eerste Tol est un habitat intime et stratifié dans un environnement hostile avec des services limités, situé dans un contexte naturel spectaculaire et « vierge ». L'habitat reflète ce caractère hostile dans ses cottages sans fioritures, ses schémas de déplacement intimes et les mentions du feu et du vent dans les entretiens oraux. La plupart des personnes qui vivent ici ont une mentalité soucieuse de la conservation et considèrent que c'est le seul aspect de la ville qui ne devrait pas changer (oral). Le projet souligne l'importance de préserver la vitalité et le caractère historique d'Eerste.

The Eerste Tol case study illustrates a landscape-based heritage approach that evaluates and guides development. The study similarly emphasises a cultural landscape perspective aligned with UNESCO and ICOMOS frameworks, advocating for an entangled relationship between nature and human settlement. Although the world heritage site within which the settlement of Eerste Tol is located is nominated for its natural properties, Eerste Tol itself is considered a cultural site within this context. It is therefore from this perspective that the authors of the document comment on the development proposal. The Eerste Tol hamlet is an intimate and layered settlement in a harsh environment with limited services, set in a spectacular and spectacular natural context. The settlement reflects this harsh character in its unadorned cottages, intimate patterns of movement, and mentions of fire and wind in oral interviews. Most individuals living here have a conservation-conscious mindset and view this aspect of the place as one that should not change. The project emphasises the importance of preserving the vitality and character of the historic Eerste Tol hamlet, integrating sensitively into its cultural landscape.

Introduction

Cultural landscapes are what one generation inherits from another carrying the embedded values, beliefs, and practices of those who came before. Each generation has the responsibility to evaluate this inheritance, not only in terms of short-term utility or self-interest, but also from a more inclusive, communal, and long-term perspective. Because human nature often leans toward self-interest, there is a vital need for governmental oversight and systems - particularly through planning and heritage resource management - to ensure that community benefits and long-term sustainability are upheld.

This study examines how a cultural landscape approach was employed to inform a proposed development at the Eerste Tol hamlet in Bainskloof Pass. The combined methodology used to assess the hamlet’s significance included tools such as the outline of the Burra Charter (UNESCO, 2024), Landscape Character Assessment, components of the Historic Urban Landscape Approach (HUL) (UNESCO 2024), which includes oral history, and a value evaluation theory by Job Roos (2007).

This multi-layered process revealed a range of cultural values and generational perspectives embedded in the landscape. It highlighted how memory, meaning, and place intersect, and how these insights can shape thoughtful, place-specific development strategies.

Project Background

The proposed development involved constructing a new house on an existing structure's platform. In response to the obligatory submission of an application to demolish a structure within a heritage area, the Heritage Western Cape (HWC) Built Environment and Landscape Committee (BELCOM) requested revised architectural proposals that addressed heritage indicators, such as scale, form, massing, orientation, and contextual relationships. It specifically requested a study by a cultural landscape specialist to determine the heritage indicators, and the client subsequently appointed Cape Cultural Landscapes to conduct the study. This process is noteworthy, as the significance of the landscape prompted Heritage Western Cape to insist on a revised architectural design.

Classifying the cultural landscape within World Heritage regulations

UNESCO classifies cultural landscapes into four categories, denoted by Roman numerals (i) to (iv). Eerste Tol is an organically evolved, continuing cultural landscape (ii). Organically evolved landscapes result from an initial social, economic, administrative, and/or religious imperative and have developed their present form by association with and in response to their natural environment. Such landscapes reflect the process of evolution in their form and component features; the continuing landscape retains an active social role in contemporary society, closely associated with the traditional way of life, and in which the evolutionary process is still ongoing’. At the same time, it exhibits significant material evidence of its evolution over time (UNESCO, 2024). Other categories for cultural landscapes include relict or fossil landscapes (i), associative landscapes (iii) or designed landscapes (iv), created intentionally by man.

Methodology for understanding significance in Cultural Landscapes

Analytically, landscapes and cultural adaptations to them may be defined in terms of their skeletal frameworks. The topography (dramatic mountains, foothills or alluvial plains) is seen as the structural frame, while traditions inform the cultural adaptations displayed as ‘clothing’. In heritage disciplines, this is known as topomorphology, which is the study of landscapes and settlements derived from authentic spaces and structuring elements.

Landscape Character Assessment (LCA) provides a framework for understanding landscapes: their qualities, vulnerabilities and capacity for change. It identifies natural and cultural patterns, as well as the elements that give a place its distinct character (Swanwick, 2002). In this context, LCA was adapted to include five core value lines (Roos, 2007) - ecological, aesthetic, historic, social, and economic - which inform development criteria for protecting and managing heritage significance. Value is a complex concept to explain or determine; every value has worth for someone for a specific reason. Value can be further explained by character and remains one of the only values found in the existing or present. Value is found in the vulnerable, coincidental and unexpected (Roos, 2007). ‘Character’ is understood as a consistent pattern of elements that creates a sense of place, while ‘Significance’ arises when both the whole and its individual elements are recognised as valuable. Consequently, the outline of the Burra Charter emphasises the assessment of significance, and from this assessment several obligations arise that guide decision-making.

Much of the intimate knowledge of the production of this landscape resides within the collective memory and lived experiences of generations that shape Eerste Tol. We drew on stories shared by residents, but these exchanges only touched the surface, offering glimpses into a deeper, more complex reality that continues to evolve.

Context of Bainskloof Pass

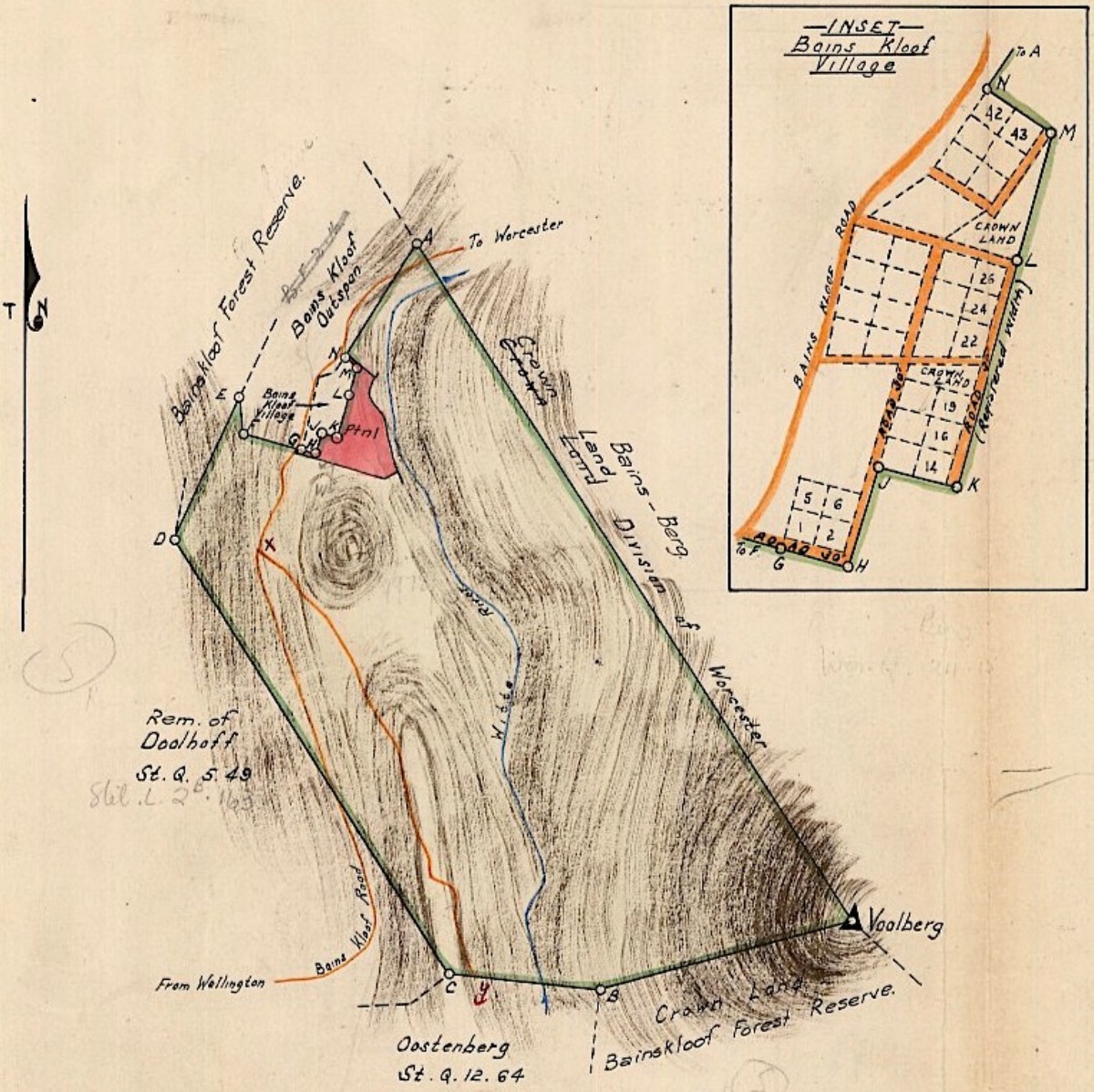

The Bainskloof Pass was built by Andrew Geddes Bain and opened in September 1853 (Rust, 2001). The pass provided the only ingress to the north through the wall-like mountain range for a century before traffic shifted to Du Toitskloof Pass in 1949. Eerste Tol served as a tollgate and an outspan - a place where vehicles could cool down and animals could rest and be re-shod before continuing their journey. To this day, Eerste Tol retains a strong sense of 'arrival', yet little remains to help visitors orient themselves and interpret its layered history, apart from a plaque on the outspan side of the pass, which was placed there to commemorate its 150-year celebration.

Described as one of the most beautiful and oldest mountain passes in South Africa, Bainskloof Pass traverses a rugged and ecologically rich landscape that now forms part of a recognised Cape Floral Region World Heritage Site that is unique for its floral biodiversity: ‘it contains the highest ratio of plant species per land area in the world - a total of 8600 species of which 5800 is endemic’ (Bainskloof, 2025).

Bain once described a day spent surveying the route as one of the hardest working days of his life (Rust, 2001). Bain would incorporate a dry masonry method of construction to build the pass, where it winds through the Limietberg Mountains (“limiet" meaning border or frontier) which were once considered the edge of the Cape Colony. The Limietberg Nature Reserve was declared a National Monument in 1980 and included in the Cape Floristic Region World Heritage Site in 2004 (UNESCO, 2024).

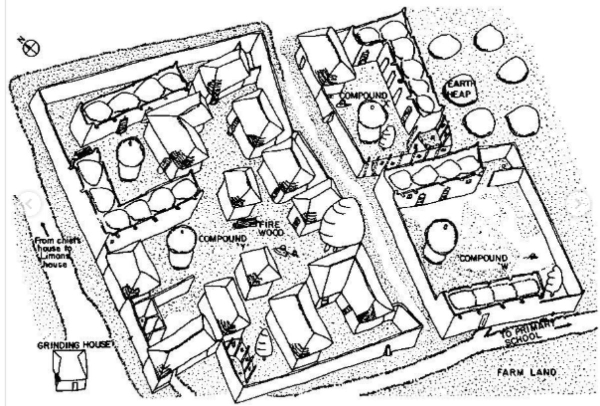

Landscape Character - Description of the Eerste Tol Settlement

In defining the Landscape Character, broader Landscape Elements (geology, landform, hydrology, vegetation, conservation) were identified, explaining how the series of layers interplay in the formation of the landscape and, in turn, how these layers have informed the cultural use of these elements to become place-specific features. The settlement of Eerste Tol is oriented along the main pass road, shaped by the need for shelter among rocky outcrops and access to the Witte River, which remains the primary drinking water source for its residents. Although erven were formally laid out in 1906 on a grid, the houses appear to grow organically from the terrain, overlaying earlier use as a convict labour construction camp for the Bainskloof Pass during the Bain era (Rust, 2001).

Significant heritage elements include early archaeological traces, stone structures, graves, and vernacular cottages such as Coaten Cottage, built with huge boulders, and the ‘Af-en-toe’ house, said to have been constructed from blasted rock and built into a rocky outcrop. Many cottages, modest from the front, reveal second storeys at the rear, using the slope and oversized boulders to advantage. The destruction of the Bainskloof Hotel in 1964 left a notable historic void, while several church groups maintain a continued presence elsewhere in Eerste Tol.

Vegetation consists of a mix of indigenous species and historic exotics, with ongoing efforts to control invasive species where the larger area used to be covered in Black Wattle. The area attracts tourists for its scenic and botanic value, yet restricted access to hiking routes causes tensions between visitors who use Eerste Tol as a hiking base and residents. The river is central to the social value of Eerste Tol as a public amenity for many years, and rocky outcrops surrounding the settlement are used for social gatherings. Farmers of the area used Eerste Tol as a summer residence to escape Wellington’s heat. The river had pools designated for men, and women, respectively (Du Toit, 2025). The old picnic structures and access to the river have been fenced off by residents (Anonymous, 2025), giving the settlement a ‘deliberate’ unwanted feel, but despite its insular quality the settlement maintains a strong connection to its natural surroundings and a distinct sense of place.

A discreet pedestrian walkway (red), often unnoticed by outsiders, links residents to the viewpoint and the river, while hiking routes connect the settlement to the broader landscape. Key public spaces (yellow dots) include the valley viewpoint (left), the open space adjacent to Coaten Cottage (middle), and the river (right). The social significance of the site is high due to its proximity to the main walkway to the river and its location near the rocky outcrops. Several Landscape Character Units were identified within Eerste Tol during the study. These consist of the Red Unit: Historic Core, Yellow Unit: Bygone Era - lacking character, Green Unit: ‘Tucked’ Vital Core, Orange Unit: Nestled landscape with ‘protruding’ structures, and the Blue Unit: Public Space.

The site falls within the ‘green unit’ and is characterised by consistency in green roof colour and predominantly white-painted stone walls, which create a visual identity, with some orange-toned structures where the use of stone is absent. Verandas or stoeps are common, usually set along the ‘long’ side of buildings and integrated into the slope. In this particular part of the landscape, embedded stoeps are a typological feature. They differ from those in other areas of Eerste Tol, where stoeps protrude from the building on its short edge, and in other units elevated stoeps emerge from rocky outcrops. Dense vegetation and undulating terrain give this cluster a ‘tucked-away’ quality, distinguishing it from other character units.

Significance, obligations and value lines in the broader context

Based on the five value lines (see methodology), with historical continuity at the core, the following section informed decision-making. It provided a framework for evaluating architectural design. It outlines the general features of the broader area and consolidates the architectural response to the more site-specific indicators. The site lies on the boundary of a World Heritage Site with critical biodiversity, requiring ecological sensitivity in all interventions. No exotic species should be planted, and endemic planting should be promoted in placemaking strategies. Development must enhance biodiversity corridors to allow wildlife movement, with fencing and visitor management designed to encourage both ecological and physical permeability. In line with Drakenstein Municipality’s framework for Eerste Tol, no new development should be allowed outside the existing footprint (Drakenstein, 2016). The area’s economic potential is tied to its natural beauty and attraction for specialist recreational visitors.

The sensitive redevelopment of the old hotel site presents an opportunity to restore legibility to Eerste Tol while serving an educational role that could absorb tourist activity and mitigate tension between residents and visitors. By offering a clear point of arrival, this approach reduces the likelihood of tourists wandering through the settlement without purpose. The secondary road in the village should be kept to its intimate scale. Social features such as the main river walkway and rocky outcrops that serve as gathering points are integral to the settlement’s identity. They must be responded to in design, with the new structures carefully integrated into the landscape without disrupting the sense of place along the socially significant walkway, yet open to connect with the use of the natural outcrops that should be celebrated as a feature. Layering of history forms an essential component of any site as a continuous narrative, and new work should be clearly recognisable on the site.

Site-specific criteria

The study identified key heritage guidelines to ensure the proposed architectural design integrates effectively with the surrounding cultural landscape. A key guideline is that the building should remain simple, using no more than three materials, and echo the modest cottages historically built in this harsh, secluded environment. Its height must not exceed that of nearby structures, relying on the existing vegetation to blend a larger form into the setting. Without the existing natural vegetative screen, development near the pedestrian route to the river should be avoided. Quartzite or dolerite stone may be utilised in its raw form, showing historic layering. Many of the historic rock walls have been painted in white in Eerste Tol. Corrugated iron is preferred for roofing, and timber material not advised due to fire risk. The diagonal orientation of the original structure, which aligns with nearby graves and the footpath rather than the settlement grid, should be respected. The presence of graves - possibly relocated closer to the building - remain protected under the NHRA. The new design should include a stoep embedded within the landscape and incorporate the rocky outcrop, potentially integrating one of its boulders as a braai (barbeque) or bonfire platform. Finally, security should be achieved through features such as shutters instead of fencing, maintaining openness, visual permeability, and a connection to the natural surroundings. These guidelines are discussed in more detail in the official report.

The architects were aware of the heritage value of the site, but their considered design required further adjustment to respond to the site’s significance in terms of its contextuality and its contribution to the cultural landscape. Their initial response to the original cottage’s diagonal layout was to propose a second storey aligned to the grid pattern, clad in rock and timber, which resulted in a visually congested façade in relation to its context. Following the study’s guidelines, a revised design reduced the number of materials, and introduced the stoep embedded along the building’s long façade. Security features were also integrated within the building envelope, ensuring both physical and visual permeability to the surrounding natural context. After further iteration, the architects successfully adjusted their design to fit within the context that incorporates the rocky outcrops on site, while retaining their initial response of the added second story that responds to the grid. Although the proposed building is larger in scale than the original cottage, it remains consistent with the area’s character, provided that its height aligns with neighbouring structures. The final decision regarding approval of the building rests with Heritage Western Cape.

Conclusion

The significance of the landscape lies not only in its individual elements but in the way they form an integrated whole. Its value is embedded in the relationships between features, their broader context, and the processes that produced them - an entangled dimension characteristic of cultural landscapes.

While development is often inevitable, this case study highlights the importance of analysing cultural landscapes so that change can sustain and amplify what is essential.

At Eerste Tol, conservation-conscious development aligned with UNESCO principles is critical. The proposed development has the potential to bring new vitality but also risks undermining the settlement’s character. This study aims to inform the proposal, ensuring it aligns with its unique setting and provides a framework to balance heritage conservation, ecological integrity, social values, and architectural design. In doing so, it supports the continued vitality of Eerste Tol as part of the Cape Floral Region World Heritage Site.

Landscape Architects, trained in the theory of cultural landscapes, are well-equipped to interpret why landscapes are valuable, envision their potential, and identify strategies that guide change across various disciplines. At Eerste Tol, guidance was intentionally broad, avoiding overly prescriptive rules so that architectural responses could emerge naturally from the site.

References

Cape Farm Mapper (CFM ver 2.1.4) accessed online at: https://gis.elsenburg.com/apps/cfm./

Drakenstein Municipality, 2016. Drakenstein Spatial Development Framework: A Spatial Vision 2015-2035, Annual Review 2016/2017. Planning and Economic Development, Drakenstein Municipality.

Roos, J. (2007) ‘Discovering the assignment, Redevelopment in practice’, The Netherlands CA Delft: VSSD.

Swanwick, C. (2002) Landscape Character Assessment, Guidance for England and Scotland, accessed online http://www.snh.org.uk/pdfs/publications/LCA/LCA.pdf.

Rust, W. (2001) Bain’s Kloof & Other Mountain Tales. Wellington: Wellington Museum.

Winter, S. 2012. Drakenstein Heritage Survey Volume 1: Heritage Survey Report. Prepared by the Drakenstein Landscape Group for Drakenstein Municipality, October.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2024. Cape Floral Region Protected Areas. [online] Available at: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1007/ [Accessed 8 June 2025].

UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2024. Cultural Landscapes. [online] Available at: https://whc.unesco.org/en/culturallandscape/ [Accessed 8 June 2025].

Credits

Oral Interviews:

Anonymous., 2025. Oral interview, interviewed by L. Jansen & M. Franklin, Wellington, 11 April 2025.

Steylter, F. and Steylter, K., 2024. Oral interview, interviewed by M. Franklin, Eerste Tol, 8 April 2025.

Wegelin, C., 2025. Oral interview, interviewed by M. Franklin, Wellington, 9 April 2025.

Wegelin, E., 2025. Oral interview, interviewed by M. Franklin, Wellington, 10 April 2025.

Du Toit, S., 2025. Oral interview, interviewed by L. Jansen & M. Franklin, Wellington, 11 April 2025.

Lotriett, D., 2025. Oral interview, interviewed by L. Jansen & M. Franklin, Wellington, 11 April 2025.

Banner image: Outspan and Tollgate in the early years (Source: Wellington Museum.