Reclaiming Africa's Landscape Identity: Moroccan Perspectives

Le paysage mondial actuel est marqué par d'importantes dynamiques en constante mutation. Dans ce contexte, l'Afrique illustre un cas pertinent, où de profondes transformations urbaines côtoient une riche diversité culturelle et naturelle. Ces particularités exigent un paysage et une architecture qui, loin de la reproduction des modèles étrangers, répondent aux spécificités locales.

Cet article interroge comment valoriser l’identité locale pour concevoir des paysages plus durables, en évoquant des analyses qualitatives de cas d’études concrets au Maroc, mettant en lumière les limites des approches importées, et l’utilité de l’adaptation aux dynamiques culturelles, sociales et écologiques propres au territoire.

Les résultats montrent que l'intégration des connaissances vernaculaires, des processus participatifs et d’une sensibilité multisensorielle propres au contexte permettrait le renouvellement des pratiques professionnelles pour lesquelles l’article plaide en particulier. Cette approche inclusive invite à repenser la relation entre espace et société, en articulant développement urbain et développement durable de nos paysages: en dépassant les conceptions figées ou importées, elle ouvre la voie vers des paysages vivants, dynamiques et co-construits avec les acteurs locaux. Ainsi, l’identité locale devient un levier d’innovation et de résilience face aux défis climatiques, sociaux et économiques contemporains en Afrique.

The present global landscape is defined by pronounced shifts and evolving population dynamics. Within this framework, Africa is a prominent case with sweeping urban changes and diverse cultural and natural patterns that call for responsive landscape and architectural designs instead of generic foreign copies. This article shows how we can sustainably design landscapes by leveraging local identity. It is based on qualitative analyses of case studies in Morocco, which highlight the decline of borrowed approaches and underscore the need to address distinct local cultural, social, and ecological dynamics. Research results suggest an inclusion of vernacular knowledge, participatory frameworks, and context-specific multisensory awareness as means to revitalising professional practices, the primary focus of this article. Such an approach supports reconceptualising the geography of social life by integrating urban and sustainable landscape design to reshape what has been static for too long. This shifts the approach to planning and designing externally imposed landscapes towards living, ever evolving, and dynamic ones. By doing so, local identity becomes a driver of Africa’s innovation and resilience, helping communities navigate climate, social, and economic pressures.

Introduction

In a rapidly urbanising and ecologically rich Africa, architecture and landscape architecture need to conform to the unique characteristics of the land: its topography, geography, waterways, climate, vegetation, culture, social dynamics, and historical context rather than pre-determined design models developed elsewhere, as there is a growing need to foster planning and design approaches that arise from within African contexts.

For decades, architecture and landscape design across the continent has often reflected external influences, resulting in projects that, while notable and visually appealing, may not fully resonate with local lifestyles. The replication of design templates comes sometimes at the expense of traditional knowledge systems, locally adapted techniques, and the relationship between communities and their environments (Janse van Rensburg, 2017).

Imported models, influenced by foreign concepts, do not always correspond to the specific ecological, cultural, and social contexts of local landscapes, which represent essential frameworks for expressing identity and environmental sustainability. In architecture and landscape architecture, these models frequently prioritise form, function, or economic objectives over the integration with the ecological and cultural contexts (Mabogunje, 2003; Olujimi, 2020).

This article suggests rethinking African architecture and landscape architecture practices by discussing local identity as both a design driver and a source of innovation, focused on the following central question: How can we valorise local identity to create fairer and more sustainable landscapes in Africa?

To address this, we argue that a transformation in professional practices especially, as well as education approaches, are essential for shaping future landscape visions across the continent. African landscapes - whether urban, rural, fluvial or coastal - are shaped by rich cultural layers and resilient ecological strategies. Embracing this complexity opens new possibilities for inclusive, holistic, participative, and therefore more sustainable designs.

Through a critical review of recent literature and grounded case studies from Morocco, we attempt to highlight the value of indigenous knowledge and participatory (collaborative) processes in shaping more responsive and equitable landscapes. The approach is informed by interdisciplinary insights, linking spatial design to environmental justice, climate adaptation, and cultural continuity.

Indigenous Knowledge and Imported Models in African Landscapes: Insights from Morocco

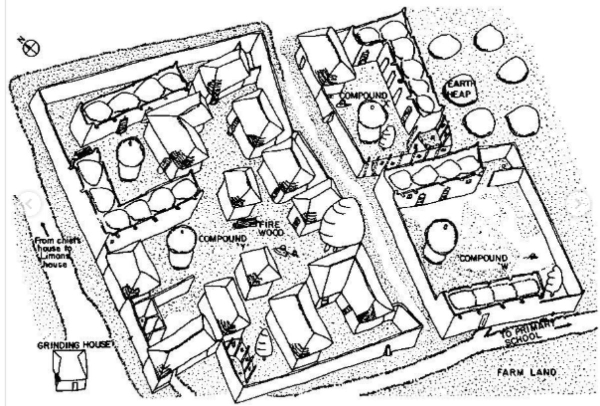

Across the African continent, and the Moroccan territory specificly, landscapes are changing rapidly in response to demographic growth, urban expansion, and climate pressures. However, these shifts often happen in a context marked by inadequate fragmented planning patterns and limited attention to local realities. In many cities, informal settlements invade wetlands, peri-urban areas face degradation, and green space distribution remains inconsistent (Brockington et al., 2021).

The African Landscape Convention acknowledges these pressures, noting that "the scope and nature of the pressures on the landscape continue to increase", calling for comprehensive principles to counter these pressures while supporting diverse aspects of contemporary landscape practice across the region.

At the same time, landscape architecture as a discipline remains underdeveloped in many African countries, often treated as a technical extension of urban planning rather than a distinct field that considers environment, culture, and society (Chipungu, 2020). As both an art and a science, collaborating with nature to serve human needs is crucial "at the locus and with the locus" (Freire & Carapinha, 2024). This gap makes it harder to build context-based architecture and landscape narratives.

The reliance on imported landscape models within the African contexts, including Morocco, is the outcome of intersecting historical, political, economic, and ideological processes.

While colonial planning practices laid an initial foundation by establishing spatial orders emphasising control, separation, and resource extraction above native systems, post-independence governments, in their quest for modernity and international visibility, often pursued development models drawn mainly from Europe. International donors and architectural firms reinforced this pattern, promoting standardised blueprints such as "green city" or "smart city" across African capitals with limited local adaptation (Watson, 2014).

In Morocco, several cases illustrate the consequences of neglecting local identity and indigenous contexts. The modular honeycomb design, for instance, developed in the 1950s for housing projects in Casablanca and inspired by European modernist architecture principles, draws attention to the challenges of implementing foreign architectural forms in local environments. Though intended to provide effective solutions for rapid urban growth, the design failed to adequately consider typical Moroccan living patterns, such as the use of private courtyards and community-oriented areas, as well as the regional climate conditions. To better meet their social and environmental needs, locals gradually modified their houses by enclosing balconies and open rooms (Kellett, 2012).

When spaces fail to reflect community values or ecological realities, they are less likely to be maintained or valued over time. In practice, this translates into vacant or underused spaces, both built and open (such as parks, empty plazas, etc.)

Inspired by European waterfronts, the redesign of Rabat's “Bouregreg Valley" illustrates these consequences of neglecting local identity and ecological knowledge in landscape interventions. The project aimed to create a modern waterfront with promenades, commercial areas, and marinas. While visually appealing, the intervention has been criticised for marginalising traditional uses of the riverbanks by local fishing and farming communities, whose access and cultural ties to the valley were overlooked (Hamdouch & Benbaba, 2015)

Local systems offer context-specific perspectives on how people historically adapted to their environments. Through seasonal land use or communal grazing strategies, these practices are active responses to ecological and social change and ignoring them can have direct environmental consequences. For instance, the replacement of traditional oasis farming systems in southern Morocco with large-scale palm monocultures (single crops) has led to soil exhaustion and groundwater depletion, disrupting the historical ecological balance that was maintained by local practices (Bourbouze, 2000; Simenel, 2011).

Thus, understanding the present state of African landscapes requires engaging both with the aesthetics, social, ecological and economic imprint of imported models, and with their institutional and ideological origins.

Local Identity Valorization Challenges and Future Landscape Perspectives

From an educational point of view, the current education system often neglects vernacular (local) knowledge. The predominance of scientism in African education has marginalised African Indigenous Knowledge, which is holistic, spiritual, and deeply ethical (David, 2024). Furthermore, even when indigenous elements are studied, they are often implemented without a clearly defined background (MDPI Land, 2020).

Ignoring local identity in architecture and landscape education makes it difficult for future actors to respond to their own environments. It also supresses creativity based on local realities. Indigenous knowledge is not simply traditional: it represents a complex framework for understanding human-environment relationships. As a knowledge system, it is adaptive, context-based, and deeply linked to sustainability, offering grounded approaches that challenge imported design paradigms, emphasises holistic and relational thinking where landscapes are understood not solely as resources to be managed, but as living systems of which communities are an integral part (El Echcheikh, 2024). This theoretical perspective positions local communities as knowledge producers rather than passive recipients of external expertise (David, 2024; Janse van Rensburg, 2017).

This transformation requires methodologies that actively involve communities throughout the design process. The work of architects like Diébédo Francis Kéré demonstrates how participatory design can successfully integrate local knowledge with contemporary needs, using locally sourced materials and traditional construction techniques while creating innovative solutions for modern challenges. A community-centered approach shows how professional practice can be revitalised through genuine engagement with local contexts. (Kéré, 2022).

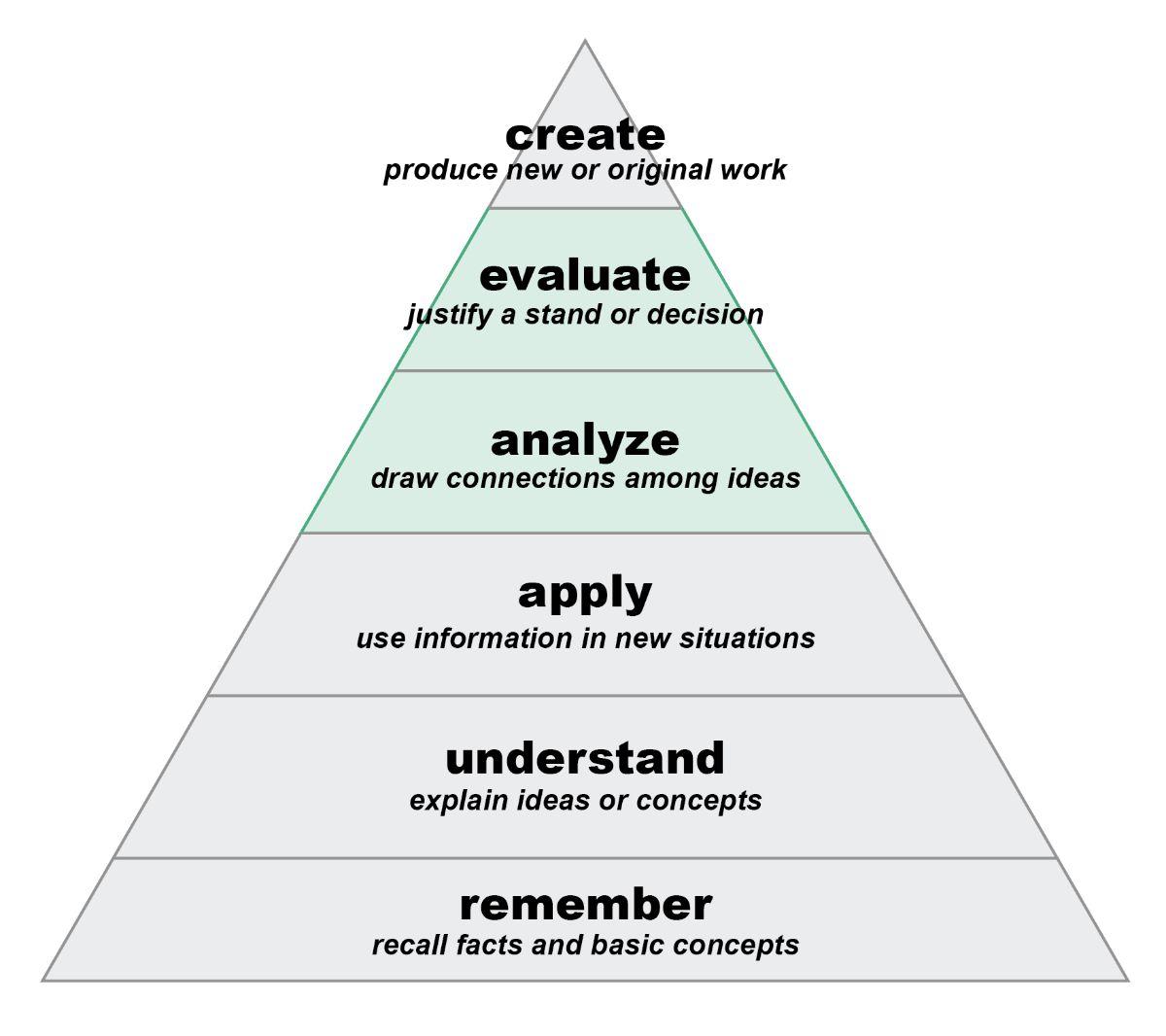

Education systems, therefore, must enable a pluralistic understanding of space, where students are trained not only to master form but to navigate ecological and cultural values, histories, and community ties. Teaching methods can include site immersion through extended fieldwork (Freire & Carapinha, 2024), storytelling by elders, mapping exercises, and cross-regional comparisons within Africa. These steps can make landscape education more responsive and transformative (Janse van Rensburg, 2017).

This multifunctional understanding of space resonates with approaches developed in Mediterranean landscapes, where traditional patterns demonstrate the value of diverse, intricate mosaics that combine production, protection, and recreation spaces. Successful landscape design emerges from understanding the "unity, diversity, and complexity" of natural and cultural systems (Freire, 2014). These principles - adapted to African contexts - can inform landscape designs that integrate agricultural, ecological, and social functions within coherent spatial frameworks.

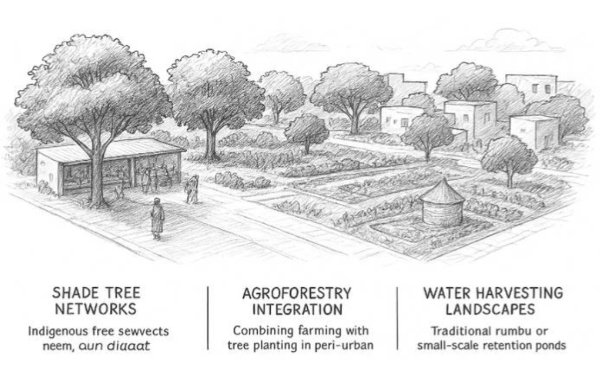

Africa's landscape is highly varied, home to a variety of distinctive biomes and ecosystems - deserts, savannas, highlands, or coastal plains - each shaped by its own climate, ecology, and cultural traditions.

But beyond understanding these broad landscape types, it's important to understand each place within the landscape, which has its own identity, extending beyond biophysical characteristics and incorporating sociocultural, economic, and aesthetic components, related to how people live, create, and relate to the space in which they live. It is important to recognise the ecological memory and collective memory of the population. Yet despite this richness, many design interventions across the African contexts continue to follow generic models (SAGE, 2019).

A contextualised design approach considers terrain, soil, climate, vegetation, as well as cultural patterns and emotive components. Oases and palmeries, as we could see, are landscape infrastructure created on ancestral techniques of water harvesting and microclimate control (El Echcheikh, 2024).

In response, the African Landscape Convention emphasises the need for responsible, creative, and sustainable approaches to preserve, adapt and enhance landscapes, that are not only economically resilient but that also support physical, emotional, spiritual and cultural people’s wellbeing.

This shift calls for design as cooperation, rather than just a projection or drawing plans: it is about being present, listening, and responding. Architects, landscape architects and professionals involved in landscape transformation must develop a deeper sensitivity that moves beyond visual analysis to include the full sensory experience of a place (its sounds, textures, movements, and atmospheres). These are the elements that give a space its true character, and they must guide how we work with it (Chipungu, 2020).

Architects and landscape architects are to especially immerse themselves in local contexts, working with communities to co-create spaces that meet real needs and reflect lived realities, developing tools and frameworks for adaptive reuse (functional conversion) and landscape flexibility that honor vernacular and ecological rhythms.

The importance of natural systems in defining urban areas can be underlined by considering the case of Kénitra, a north-western coastal Moroccan city established along the “Sebou” River, The city has seen a number of initiatives aimed at modernisation and aesthetic upgrading, gradually breaking the city's symbolic and historical connection to the river, turning a landscape landmark into a neglected space.

The case study shows how landscape and architectural identity is related to experienced multisensory interactions with contexts rich in historical, ecological, and cultural value rather than just image-based improvement. Far from being just a physical element, the “Sebou” River has long served as a spatial and emotional anchor for the people of the city and the region. Its marginalisation mirrors a tendency in many modern cities to import urban forms.

Therefore, reclaiming architecture and landscape identity demands more than aesthetic measures and cultural references; it calls for re-establishing the connection between the city and its surroundings. Here the landscape is a continuous system and the main structural elements should be valorised, as the rivers are live actors influencing spatial belonging and collective memory, not leftover areas or technical limitations (Marschall, 2006).

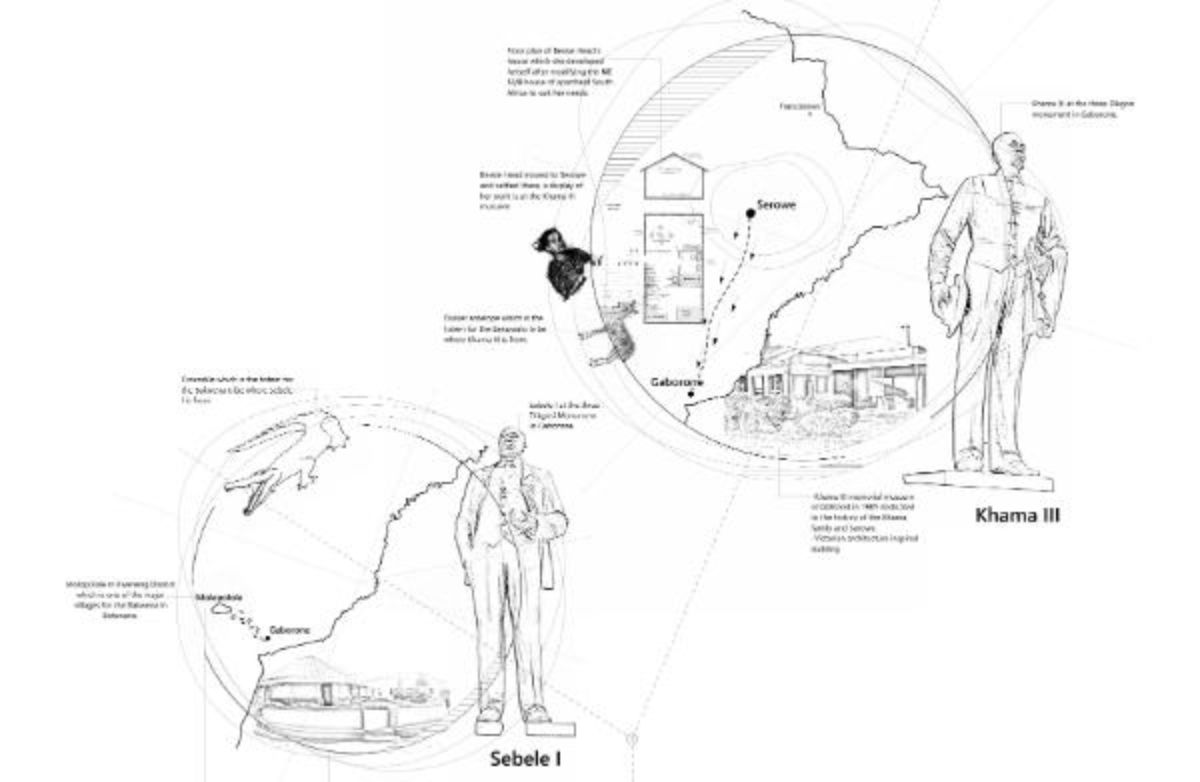

In the same spirit, it is necessary to mention heritage preservation. Contemporary heritage projects too frequently use preservation strategies created in quite dissimilar cultural and geographic environments. These imported systems run the risk of reducing the diversity of particular adaptations and concealing the subtle influences that have moulded civilisations. Drawing from local knowledge systems, vernacular architecture, and indigenous methods of inhabiting space allows heritage projects to evolve beyond institutional branding or aesthetic reproduction to become living, evolving processes rooted in local realities and identities (Chilisa, 2012).

Another example of waterscape is the case of Portuguese heritage in Morocco, which offers a helpful lens through which to rethink preservation practices. In the field of heritage, we must develop actions that involve the participation of communities in the processes of formation and expression of cultural identities, as well as the processes of valorization, classification and conservation of heritage. The Portuguese maritime city of Essaouira and its coastal installations, a UNESCO World Heritage site, embodies a complex, mixed-culture heritage shaped by centuries of communication between imported architectural shapes and local environmental and cultural conditions. These remains are active landscapes where Portuguese influences have been reinterpreted and merged into Moroccan coastal life, resulting in hybrid identities (blended cultures) that defy fixed preservation schemes.

This does not mean rejecting innovation, but rather grounding it within the multiple contexts, realities and adaptive strategies that have shaped them over time. Effective preservation must be dynamic, rooted in the understanding that identity is not fixed, but emerges from ongoing negotiations between people, place, and history. By integrating local practices into contemporary approaches, heritage work can become not only more resilient and sustainable, but also more meaningful and evolving through time.

Adapting design methodologies to the distinct climatic, ecological, and cultural conditions of each site leads to more resilient and context-sensitive outcomes. Such initiatives demonstrate that it is not about freezing heritage in time, but about respecting and revitalising living traditions, calling for inclusive, collaborative governance models and interdisciplinary approaches that imply participatory procedures (Janse van Rensburg, 2017; David, 2024).

Such transformations call for pre-emptive and inclusive processes, actively engaging local communities throughout all phases, from initial assessments to final implementations, which enhances both the contextual relevance and sustainability of landscape interventions. At the same time, such processes create essential space for collective memory, oral narratives, and intangible cultural heritage (traditions) that conventional technical approaches frequently overlook. This approach provides legitimacy and structural coherence to methodologies that might otherwise be marginalised within predominantly imported planning frameworks (Adade Williams, Sikutshwa and Shackleton, 2020).

Building fair and adaptable landscapes across Africa means understanding and nurturing the deep connections between communities and their ancestral lands.

When we imagine the future of architecture and landscape architecture designs on the continent, we need to move well past planning approaches or preserving African heritage in ways that turn living traditions into static tourist attractions.

Every actor involved in reshaping African environments should see themselves less as an outside expert importing foreign solutions and more as collaborator helping dialogue between traditional knowledge holders and contemporary needs. This means bringing together diverse voices: architects working with traditional builders, urban planners learning from indigenous land management practices, or sociologists collaborating with economists who understand local markets. This will ensure a more authentic response to the realities of rapid urbanisation, climate challenges, and economic pressures while honoring indigenous knowledge systems that have sustained communities for generations (Janse van Rensburg, 2017).

Lessons can also emerge from exchanges between African regions with similar socio-ecological realities, fostering resilience and creativity beyond global trends, as they offer proactive strategies for climate adaptation and spatial justice (equitable spaces) through indigenous practices (David, 2024).

Conclusion

Rethinking African landscapes begins with recognising the mismatch between imported models and local realities. From education to professional practice, the dominance of foreign frameworks has led to spatial fragmentation, ecological inefficiency, and cultural disconnection, showing how educational systems often silence indigenous knowledge and how practice tends to replicate global forms instead of responding to diverse African ecologies and social rhythms.

Participatory approaches to architecture and landscape architecture - integrating local materials, traditional techniques, and community engagement - provides a concrete model for how professional practice can be transformed to serve both local needs and contemporary challenges. Creating unified yet diverse landscapes through careful integration of natural systems, water management, and cultural practices provides approaches that show that sustainability emerges not from imposed solutions, but from deep engagement with local realities, community knowledge, and environmental conditions.

Fundamental shifts toward experiential methodologies that engage with cultural sensitivity and ecological awareness is a requirement for transformative learning. Demanding more than just technical skill, architecture or landscape architecture requires a deep sensitivity to the ways people inhabit and shape their surroundings, and should engage with local practices, materials, and ways of knowing.

The aim of an inclusive approach, which is not to idealise the past or reject innovation, but to seek a new synthesis rooted in plural knowledge systems, looking forward to the future.

Morocco showcases the importance of this shift by embodying how local knowledge and diverse cultural identities can be central to landscape and architectural practices. The country’s varied ecological zones and rich historical layers illustrate the necessity of moving beyond imported models, embracing inclusive and participatory processes to create landscapes and urban environments that are both resilient and meaningful to their communities. This approach highlights how grounding design and heritage preservation in local realities adapts to contemporary challenges.

More than ever, this calls for interdisciplinary research, critical pedagogy, and political will. For this purpose, three shifts are essential: First, position indigenous knowledge holders as co-experts in design processes. Second, restructure education to integrate indigenous knowledge as foundational, incorporating holistic landscape approaches in fieldwork. Third, develop policy frameworks that require cultural impact assessments, ensuring projects consider local heritage knowledge and traditional land use practices, fostering landscapes of belonging, memory, and hope.

References

Adade Williams, P., Sikutshwa, L. and Shackleton, S. (2020) ‘Acknowledging Indigenous and local knowledge to facilitate collaboration in landscape approaches—lessons from a systematic review’, Land, 9(9), p. 331.

Brockington, D., et al. (2021) ‘Environmental governance in Africa’, Global Environmental Politics, 21(1), pp. 72–93.

Chatoui, F. (2023) ‘The City’s Landscape Identity through its River: The Case of Kénitra’ Architecture thesis. National School of Architecture of Rabat.

Chipungu, L. (2020) ‘Decolonising landscape architecture in Africa’, The Nature of Cities.

Chilisa, B. (2012) Indigenous research methodologies. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

David, J.O. (2024) ‘Decolonizing climate change response: African indigenous knowledge and sustainable development’, Frontiers in Sociology, vol. 9.

Douaa, E.A.A. (2024) ‘Climatic challenges and urban landscape design responses in hot climates: insights from North Africa’, Axi-PNAM, 18(2), pp. 22–30.

Freire, M. (2014) 'Mediterranean Landscapes: On the Ecological and Cultural Foundations Essential to the Process of Landscape Transformation', in Rodrigues, A. D. (ed.) The Garden as a Lab: Where Cultural and Ecological Systems Meet in the Mediterranean Context. Évora: Centro de História da Arte e Investigação Artística, Universidade de Évora, pp. 29-42.

Freire, M. and Carapinha, A. (2024) 'Teaching with the place and body', in Learning. Life. Work – San Francisco, AMPS | California Institute of Integral Studies, pp. 1-8.

IFLA Africa (2019) African Landscape Convention, International Federation of Landscape Architects Africa Region, October.

Janse van Rensburg, A., 2017. Embracing indigenous knowledge in landscape architecture: Towards a culturally grounded design practice in Africa. Landscape Review, 17(1), pp.30–43.

Kéré, D.F., 2022. Diébédo Francis Kéré, 2022 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate: Empowering People through Architecture. KIEAE Journal, 22(3), pp.7–10.

Kellett, P., 2012. Modernism and the Mediterranean: Architecture and Social Change in the Postwar Era. Journal of Architecture, 17(2), pp.211-234.

Lawrence, T.J., Stedman, R.C., Morreale, S.J. and Taylor, S.R. (2019) ‘Rethinking landscape conservation: linking globalized agriculture to changes to indigenous community-managed landscapes’, Tropical Conservation Science, 12.

Mabogunje, A.L. (2003) ‘Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainable Urban Development in Africa’, Environmental Development, 5(2), pp. 20–33.

Marschall, S. (2006) ‘Landscape, memory and identity in post-apartheid South Africa’, Geographical Review, 96(3), pp. 351–368.

Myers, G. (2011) African cities: Alternative visions of urban theory and practice. London: Zed Books.

Olujimi, O.O. (2020) ‘Integrating Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Sustainable Architecture: Lessons from Africa’, International Journal of Architectural Research, 14(3), pp. 131–146.

Osunade, M. A. (1994) ‘Indigenous climate knowledge and agricultural practices in south-west Nigeria’, GeoJournal, 33(1), pp. 125–132.

Tropical Conservation Science (2019) ‘Rethinking landscape conservation: Linking globalized agriculture to changes to indigenous community-managed landscapes’, Tropical Conservation Science, 12(1).

Watson, V. (2014) ‘African urban fantasies: Dreams or nightmares?’, Environment and Urbanization, 26(1), pp. 215–231.

Zubair, A., Ali, M. and Tarar, M. (2024) ‘Climatic challenges and urban landscape design responses in hot arid contexts (North Africa)’, Axi-PNAM, 18(2).