Lessons from Kibera: Reframing the Public Realm

Le récit demeure le même : celui, bien souvent, d’étendues d’habitats informels, de déficits d’infrastructures, d’environnements en dégradation sous l’effet des pressions humaines et climatiques, et de la marginalisation de millions de personnes dans les villes africaines en pleine expansion. L’architecture de paysage constitue une discipline clé pour l’action climatique et la restauration urbaine ; pourtant, au Kenya, elle reste une profession non reconnue au sein du secteur de l’environnement bâti du pays. Aujourd’hui, il est urgent de mobiliser davantage de professionnels de l’environnement bâti là où leurs compétences sont le plus nécessaires. Plus de vingt architectes paysagistes venus du monde entier ont contribué à façonner le travail de KDI, en explorant les défis et opportunités uniques et interdisciplinaires pour des solutions holistiques au sein des quartiers urbains informels qui parsèment le paysage de Nairobi. L’expérience et les contributions de ces professionnels constituent un socle pour les apports actuels et les perspectives à venir. À partir de quelques exemples, cet article revient sur les processus et les réalisations, dans une tentative d’éclairer une vision partagée. L’analyse retrace l’évolution de la pratique de l’architecture de paysage, en se concentrant principalement sur les paysages urbains informels et sur son intégration dans le développement de méthodes, d’outils et de partenariats orientés vers la justice, l’inclusivité et la réactivité écologique. Cette approche ciblée se manifeste à travers des projets tels que le Kibera Public Space Project (KPSP), l’Urban Fabric Initiative (UFI) et le programme Realising Urban Nature-Based Solutions (r-u-NBS), entre autres. Ces initiatives ont expérimenté et appris, façonné et bénéficié de la discipline de l’architecture de paysage, offrant des enseignements et des points d’entrée ancrés dans l’adaptation transformatrice, la résilience urbaine et l’autonomisation communautaire.

The narrative is the same: sprawling informal settlements, infrastructural deficits, deteriorating environments from human and climatic stressors, and the marginalisation of millions in rapidly growing African cities. Landscape Architecture is a key discipline for climate action and urban restoration, yet in Kenya, it remains an unregistered profession within the country's built environment sector. Today, there is an immense need to deploy many built environment professionals where they are most needed. More than twenty Landscape Architects from around the world have shaped the work referenced in this article, exploring the unique and intersectional challenges and opportunities for holistic remedies within the urban informal neighbourhoods that dot Nairobi's cityscape. The experience and input of these professionals provide a backdrop for the ongoing contributions and potential ahead. Drawing on a few of them, this article reflects on processes and outputs and attempts to shed light on shared perspectives. The analysis focuses primarily on informal urban landscapes and their integration into the development of methods, tools, and partnerships for justice, inclusivity, and ecological responsiveness. The laser focus is demonstrated through projects like the Kibera Public Space Project (KPSP), the Urban Fabric Initiative (UFI), and Realising urban nature-based solutions (r-u-NBS) program and many others, that have tested and learnt, shaped and benefited from the discipline of Landscape Architecture; offering lessons and entry points rooted in transformative adaptation, urban resilience, and community empowerment.

Reclaiming the Public Realm

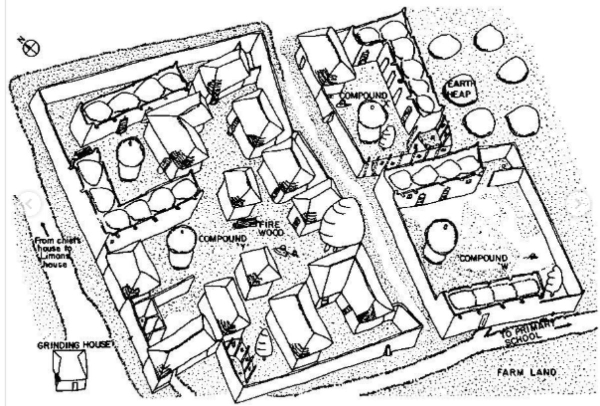

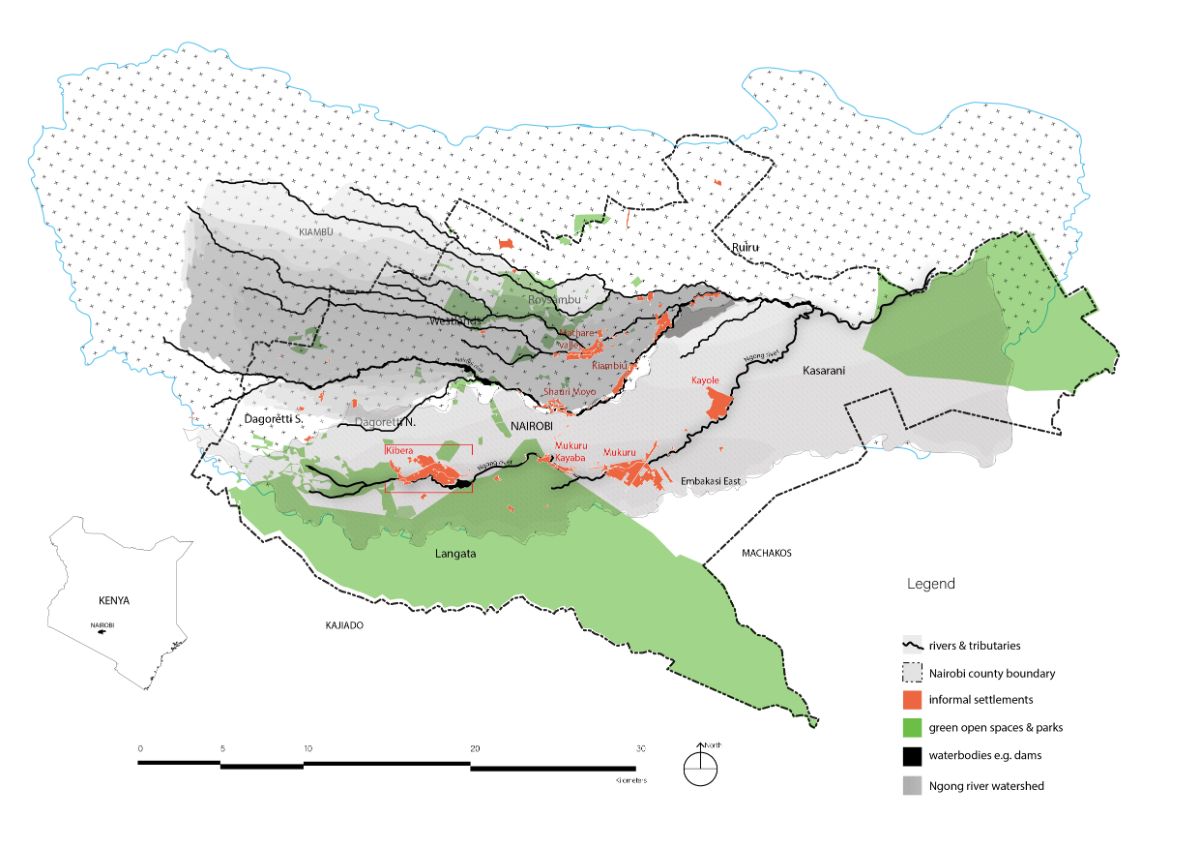

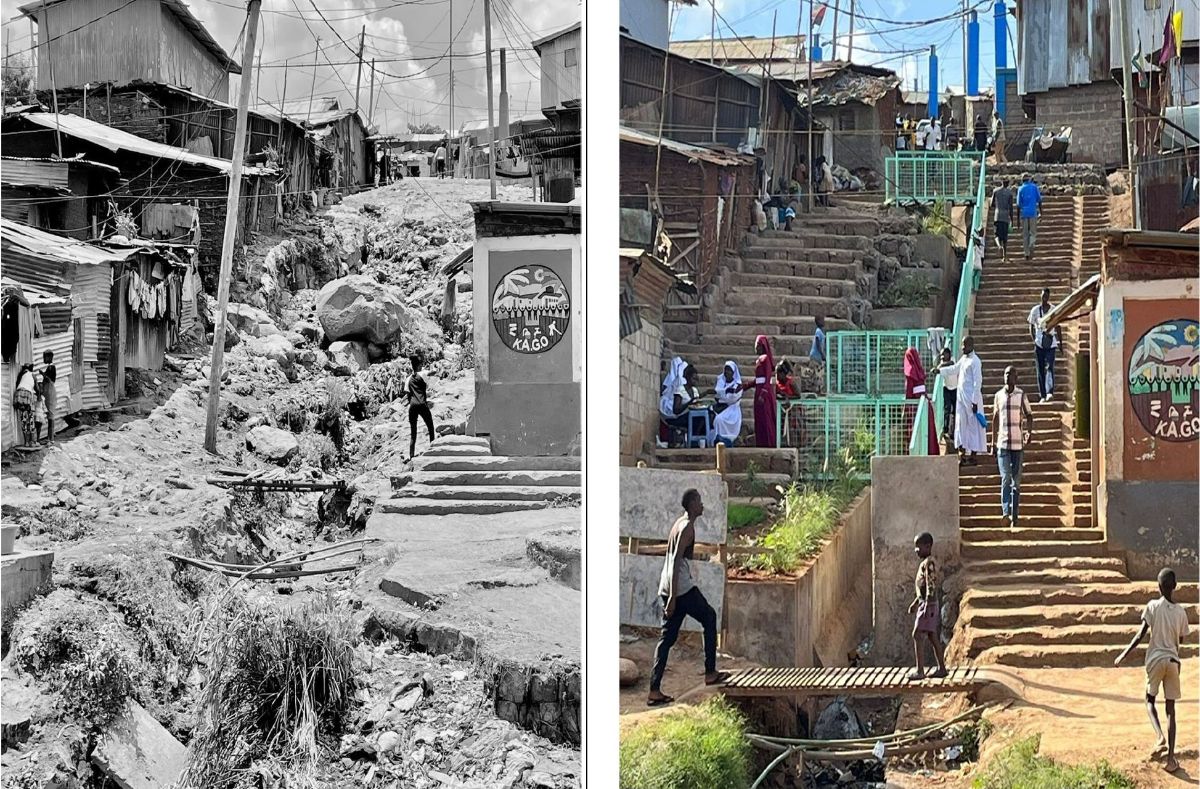

The story begins in Kibera, Nairobi, one of Africa's largest and most complex informal settlements (Dessie, 2025) associated with anthropogenic urban challenges. Deeply intertwined with the natural landscape is the colonial history of racial segregation and discriminatory land use, which left lower-income African populations in flood-prone, underserved lowlands (SHREYA MITRA, 2017). Before the settlement emerged, Kibera was a forested area where streams and river tributaries merged to form the present-day Ngong River. Today, Kibera is a densely packed area riddled with flood-prone waterways, inadequate sanitation, and an acute shortage of public space, even though less than 2% of its territory is dedicated to public space. (UNHABITAT, 2020). Instead of serving as communal resources, these waterways had become centres for crime, waste disposal, and illness (Dessie, 2025) (Figure 1).

Landscape architects, recent graduates from the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), played a key role in developing the original concept titled ‘a model for marginal landscapes’, which centred on the belief that well-designed public spaces are essential for fostering healthier, safer, and more equitable communities(Figure 2).

They were particularly influenced by the effectiveness of participatory design, which, through deep and sustained engagement with space users, produced outcomes that benefited everyone . This approach represented a significant departure from the traditional practice of delivering design projects that comprised externally imposed development models.

‘In the traditional design world, successful design depends upon a deep understanding of a client’s needs, sensitivity to physical context, practical knowledge of the resources available to complete the project, and strategies for creatively relating the three. When these criteria are applied in partnership with local residents to a design challenge in a slum, the result is a solution that is rooted in the community, contextually appropriate, technologically sustainable, and innovative in approach.’ (Monroe, 2014).

The Kibera Public Space Project (KPSP) was conceived as a practice and process to go beyond the historical shortcomings of ‘slum’ improvement projects and present an alternative future for informal settlements and urban centres at large. This idea aimed to create public spaces as a radical act of reclamation, not merely as an aesthetic or public intervention.

The project’s core idea was to transform neglected riparian zones into a network of multi-use “Productive Public Spaces” (PPS). This network would do more than introduce greenery; it would function as critical community infrastructure providing access to essential services, facilitating safe movement, supporting livelihoods, and strengthening the social fabric in a context of profound precarity. KPSP was a direct challenge to the notion that public space is a low priority in settlements grappling with basic survival.

The Method: Participatory Design as a Cornerstone of Responsive Design

The method builds on recognising differences, understanding context, and combining compassion with technical expertise, and is enabled in informal neighbourhoods through an iterative and creatively adaptable approach. Central to its transformative impact is a steadfast commitment to expanding the reach and depth of participatory co-design. It creates space for designers to deeply understand the people, place, and problem, often resulting in many small, intersectional interventions (Figure 3).

This approach sharply contrasts with the trickle-down, externally imposed development models that have traditionally failed communities in Kibera and other informal settlements. Notably, public spaces are scarce, and projects aimed at creating or upgrading such spaces were unheard of.

Significantly, the co-design process is based on the belief that residents are the true experts of their environment and that sustainable change can only happen when the entire process amplifies community voices.

Furthermore, this philosophy is reflected in a refined five-step process: demand-led assessment; stakeholder mapping and alignment; participatory planning and co-design; co-implementation; and community-led operation and maintenance. Through a series of iterative workshops, residents—including elders, women, men, and youth—jointly identify hazards, explore possibilities, and co-design every aspect of the project, from site layout to material choices. This process does more than construct physical infrastructure; it builds trust, skills, and a deep sense of ownership.

Over time, the model has been refined. For example, the landscape architects initially helped establish new community-based organisations (CBOs) for each project. Learning from experience, they transitioned to a model that leverages the well-established path of well-organised CBOs that respond to a Request for Proposals (RFP), suggesting sites and project ideas themselves. This evolution gives the community even more power from the outset, ensuring projects are rooted in local knowledge and address the most pressing needs.

Intertwined with successes, lessons have been learned from persistent challenges such as: a lack of formal land rights that make community investments vulnerable to eviction to pave the way for state-led projects; a lack of collective foresight hindering long-term planning; and public spaces often conflicting with urgent human needs like food and shelter, among others (Dessie, 2025).

Outcomes: From Degraded Rivers to a Network of Productive Landscapes

The tangible results bear witness to the power of community-led landscape design. Around Kibera, the community transformed former rubbish dumps and hazardous narrow spaces into usable public spaces (Figure 4).

However, these are not simply parks; they are dynamic, hybrid places that combine social, economic, and ecological functions. In contrast to the conventional focus on vital infrastructure such as roads, utility lines, or housing, public spaces in informal settlements complement development by providing social infrastructure and amenities.

One of the landscape architects’ key conceptual contributions is the framing of public space as core infrastructure.

These may include, often scarce services such as basic amenities (water, sanitation, drainage), act as platforms for informal economies (markets, kiosks, cooperatives), serve as buffers against climate risks (flood zones, heat mitigation), and enhance social cohesion and safety (playgrounds, meeting halls, cultural venues), among others.

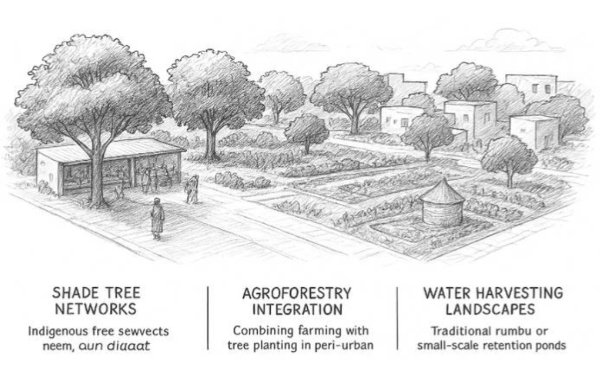

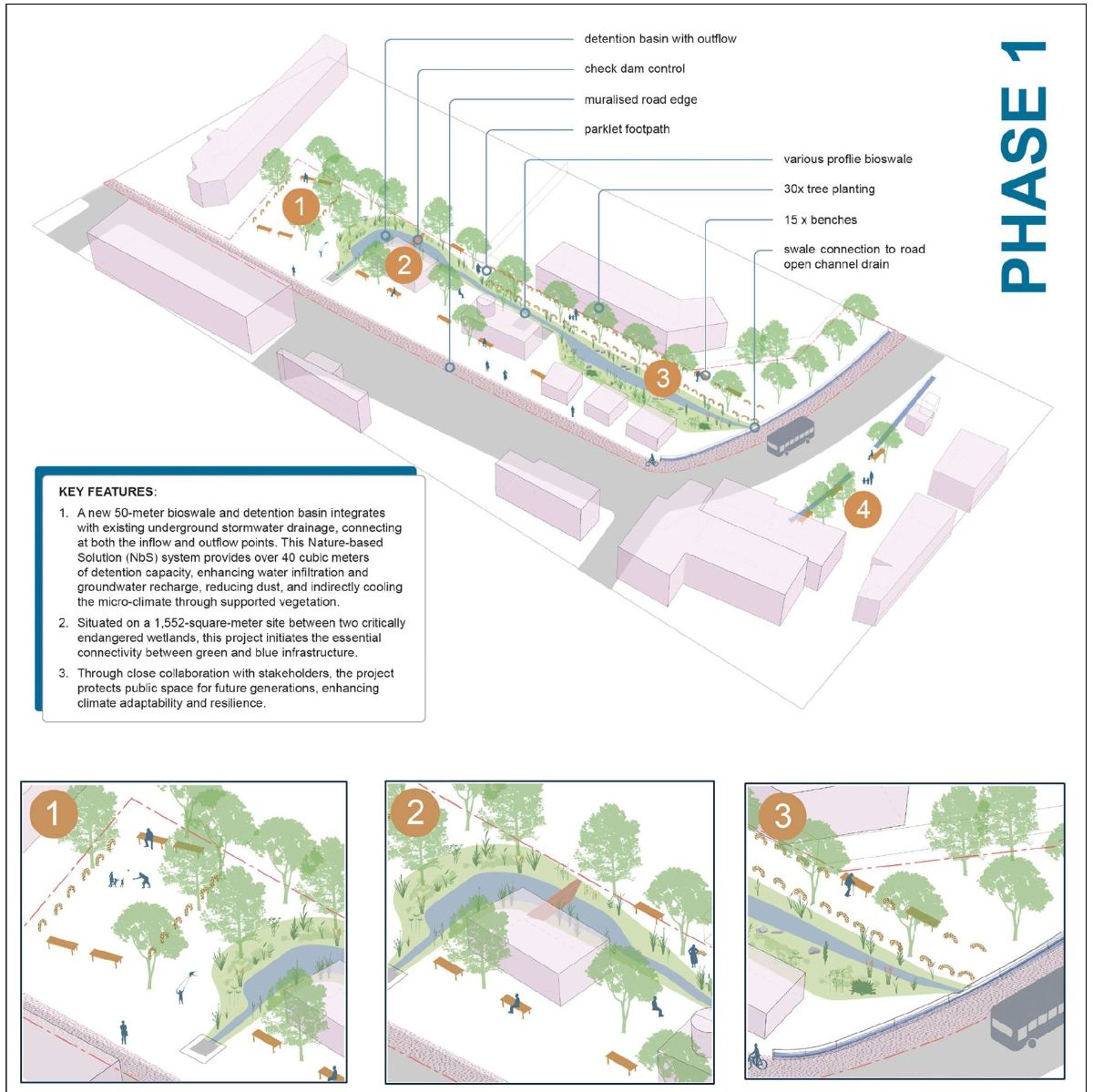

Integrating Nature-based Solutions (NbS) into public space design deepens the infrastructure framing. Public spaces under the r-u-NbS project do more than host spaces of repose or play; they also mediate hydrological flows, reduce flood risks, enhance infiltration, stabilise riverbanks, and regenerate vegetation. In the Mukuru Riverfront (Figure 5), for example, co-designed green infrastructure improves drainage, cooling, shading, and seating, allowing the space to serve both ecological and social functions .

This rethinking expands the role of landscape architecture. It demonstrates that designing outdoor spaces is not secondary but vital to creating just and resilient cities. These projects employ core landscape architecture principles to tackle urgent urban challenges. Flood resilience is managed through green infrastructure such as gabions, strategic planting, and soil remediation.

These ‘Productive Public Spaces’ in turn generate income through rentable halls and business kiosks, which fund the site’s maintenance, improve residents’ skills, and provide access to clean water and sanitation facilities. They promote social cohesion by creating safe spaces for children to play, neighbours to gather, and cultural exchange to flourish. Using this interconnected approach suggests that isolated interventions are insufficient and that developing a network of productive green spaces can help repair a fragmented urban landscape. Starting from community-scale public spaces, this approach moves towards evidence-based, scalable, nature-inspired water infrastructure integrated with participatory design (Figure 6).

Scaling and Systematising the Approach

The focus of this work expanded from implementing individual projects to increasing their impact and driving systemic change, supporting and encouraging adaptation towards transformation by connecting physical interventions to changes in governance, livelihoods, and community identity.

This evolution is evident in three key initiatives that build on KPSP's lessons. The first initiative was developed as a direct "scale-up of learnings". Integrating the UFI model aimed to align small-scale participatory projects with broader city and county frameworks, shifting the practice from an NGO-led initiative to a hybrid model that embeds participatory design within municipal governance, thereby enhancing government capacity for community engagement and coordination.

The second showcases a deeper engagement with climate resilience. The focus was to create climate justice through Nature-Based Solutions (NbS). Over a nine-month co-design process, the landscape architects worked with residents to develop a Green Infrastructure Plan that integrates bioswales, detention basins, and green streets to manage stormwater, reduce flood risk, and improve environmental quality.

Finally, insights from this approach have expanded into the policy domain with the Integrated & Inclusive Infrastructure Framework for Informal Settlements (3iF). This initiative condenses years of local experience into a practical guide for planners, policymakers, and communities, aiming to maximise the inclusivity and integration benefits of settlement upgrading efforts across Kenya.

Ultimately, these interconnected projects, now woven into the fabric of the settlement, tell a unique story of transformation. Together, they provide tangible proof of the effectiveness of the participatory process. Future directions should involve embedding these participatory methodologies into official planning systems, scaling NbS in informal contexts, and advocating for public space as a fundamental urban right.

Ultimately, the success of these projects demonstrates a profound redefinition of landscape architecture itself. Co-founder of KDI, Chelina Odbert, states in Greenspan 2018,

“As much as we love design and love its power, design alone is not enough. The approach must be inherently interdisciplinary, integrating design, planning, community organising, research, and advocacy. The success of these projects is measured not only by their physical form but also by their contributions to a holistic vision of 'equitable resilience,"

which includes four key domains:

Governance: By forming and strengthening CBOs and establishing community-led management structures, the projects build local capacity for self-governance.

Livelihoods: The projects directly support economic well-being through construction jobs, business kiosks, skills training, and savings and loan programs that empower residents, especially women and youth.

Environment: Through landscape-driven engineering, green infrastructure, and waste management, the projects restore ecological functions and mitigate environmental hazards, such as flooding.

Security: By transforming dangerous, neglected spaces into well-lit, actively used community hubs, the projects reduce crime and create a sense of collective safety and tenure, even if informal.

This integrated approach shows that in contexts of extreme inequality, the landscape architect's role must expand. It must be a facilitator, a collaborator, and an advocate, using planning and design tools to address the root causes of vulnerability.

Conclusion: Seed the ground

The examples highlighted in this paper emphasise the vital role of landscape architecture in tackling modern challenges such as urban inequality, climate vulnerability, and social fragmentation. By transforming polluted riverbanks into networks of life-sustaining public spaces, they demonstrate the potential that lies ahead as cities become more innovative, more inclusive, and advocate for the right to the city. The projects show that the most significant contributions of landscape architecture are not only beautiful but also empower communities, restore ecosystems, and lay the foundation for a fairer, more equitable world.

References

Agence Française de Développement , 2025. France through AFD inaugurates urban fabric initiative project to upgrade informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. [Online]

Available at: https://www.afd.fr/en/press-releases/france-through-afd-inaugurates-urban-fabric-initiative-project-upgrade-informal

Dessie, E. O. A. L., 2025. Kibera Public Space Project. ACRC Urban Reform Database case study..

Greenspan, E., 2018. ARCHITECT. [Online]

Available at: https://www.architectmagazine.com/practice/chelina-odbert-and-jennifer-toy-kounkuey-design-initiative_o

Kounkuey Design Initiative, n.d. 3IF: Integrated & Inclusive Infrastructure Framework for Informal Settlements. [Online]

Available at: https://www.3if.info/

Kounkuey Design Initiative, n.d. r u NBS - realising urban nature based solutions. [Online]

Available at: https://www.r-u-nbs.info/

UNHABITAT, 2020. Informal settlements’ vulnerability mapping in Kenya: The case of Kibera, Nairobi: UNHABITAT.

.jpg)

.jpg)