Towards a Visual Lexicon of South African Landscapes

Malgré une tendance croissante vers l'idée d'un aménagement « afrocentrique » des espaces publics ouverts, ce terme et son application sont également remis en question en tant que généralisation, compte tenu de la diversité des paysages et des nuances culturelles à travers le continent africain. Compte tenu de ces débats, cette étude pluriannuelle se concentre sur l'« afrocentrisme » et l'explore. En fin de compte, l'objectif principal de l'étude est de développer une ressource accessible, sous la forme d'un lexique de termes, d'illustrations et d'informations sur les typologies, les caractéristiques et les particularités des paysages et de l'aménagement paysager en Afrique du Sud.

Le document vise d'abord à recueillir des récits et des connaissances importants, et à aider les concepteurs à développer et à intégrer des informations plus représentatives en matière de conception ; ensuite, il vise à fournir une ressource plus accessible pour soutenir les collaborations entre les communautés et les concepteurs. L'article suivant rendra compte de l'avancement du projet de recherche et abordera certains facteurs clés liés au projet.

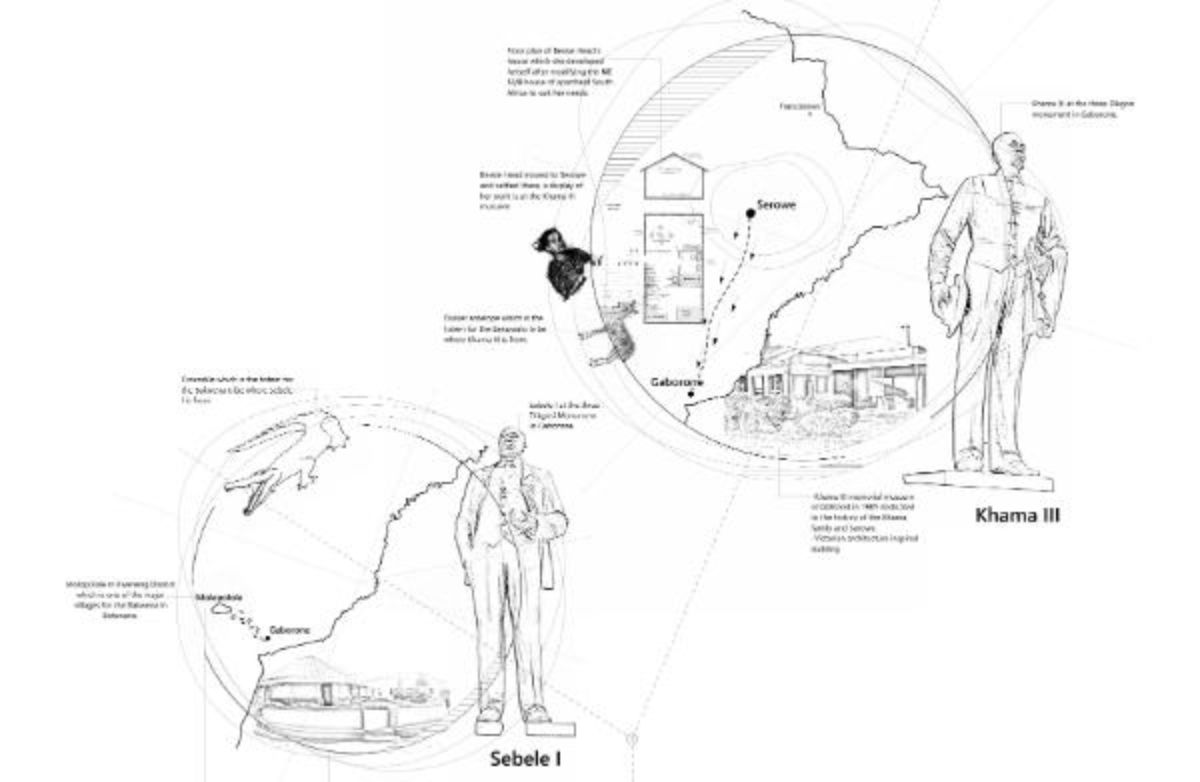

Despite an increasing shift towards the idea of ‘Afrocentric’ design of public open space, the term, and its application are also challenged as a generalisation, based on the diversity of landscapes, and cultural nuances across the African continent. Given these debates, the Storying the Landscape project is a multi-year study that centres and explores ‘Afrocentricism’ relative to landscape architecture. Ultimately, the main objective of the study is to develop an accessible resource, in the form of a lexicon of terms, illustrations and information on typologies, characteristics and features of South African landscapes and landscape design. The document aims first to capture important narratives and knowledge, and support designers in developing and incorporating more representative design informants, and secondly to provide a more accessible resource to support community-designer collaborations. This paper will report on the progress of the research project, and discuss some key factors relating to the project.

Introduction

This paper reports on the progress of the ‘Storying the Landscape’ project. Supported by University of Pretoria RDP Seed Funding, this three-year pilot project initiates a potentially larger project to provide additional, recent, and inclusive landscape reference material for the South African context. The project emerged as an outcome of a recent PhD study which considered environmental justice and local park making informants, with human-nature relationships as a central driver of both (Shand, 2022). The previous study concluded with a series of findings including the need to promote 1) better knowledge sharing across the divide of spatial design professionals and local communities, and 2) more locally representative design informants, in more accessible formats. The current study is, in part, a response to some of these findings.

The argument underpinning this work is that a comprehensive collection of reference material, in the form of a repository, visual lexicon, or illustrated reader will a) contribute towards informing alternative, locally appropriate design approaches; and b) support the improved communication and collaboration between professionals, government officials and lay-people working towards improved landscape projects. This goal ultimately necessitates a multi-year project, and requires extensive input from industry, academia, and local communities. However, the current study is considered a first phase of the complex project, and is driven by the following, overarching, research question:

How can the incorporation of various voices and stories be captured, consolidated, stored, illustrated and communicated as an accessible digital repository of landscape architectural reference material in the South African context, as an initial step towards developing a visual lexicon of South African landscape architecture?

For the purposes of the current paper, the objectives are 1) to outline the research activities linked to the project; 2) to report on the progress of the research activities; and 3) to discuss some of the key aspects that have emerged from the project to date.

An Afrocentric approach to public spaces?

In the urban context, there appears to be a disconnect between urban residents and urban nature, evidenced by the poor condition of much of the public spaces and formally designed landscapes in South Africa, and specifically in the City of Tshwane (Makakavhule & Landman, 2020). Some authors suggest that this is exacerbated by a lack of recognition and inclusion of local South African residents in the design process, and as an aftermath of the colonial and apartheid influences in the country (Shackleton & Gwedla, 2021; Makakavhule & Landman, 2020; Landman & Makakavhule, 2021).

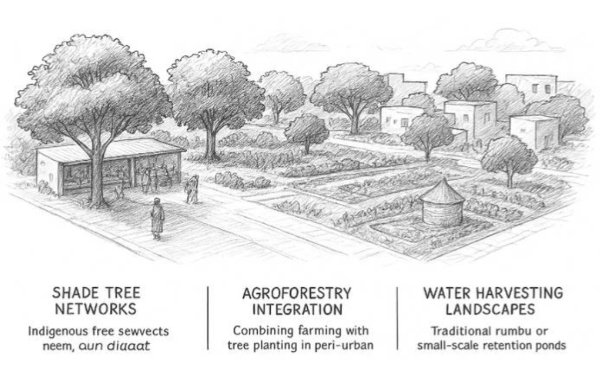

Historically, Eurocentric ideals were considered superior to local knowledge and beliefs (Chawane, 2016) – and were mirrored in the development of urban centres to emulate that of Western and European cities and landscapes (Shackleton & Gwedla, 2021). In the development of parks, public open spaces and streets, these ideals also translated to the celebration and emulation of Victorian, English style gardens, classical landscapes and ornamental plants and trees (Shackleton & Gwedla, 2021). To address the current disparity in public open space provision, and quality, authors argue that a shift towards a more ‘Afrocentric’ approach is required in the development of public open space in South Africa (Shackleton & Gwedla, 2021; Shand & Breed, 2024; Shand, 2022).

As a movement, ‘Afrocentricity’ challenges ‘Eurocentric’ norms and narratives, by centring African interests and values, and seeks to change the historical perspective by reclaiming African contributions (Chawane, 2016). From the perspective of the built environment, this position is critical, and has been considered so for years.

For example, ‘The dilemma of planning in Africa … is the phenomenon of Western-oriented theory and practice being imposed on purely African problems in a manner which does not result in the best solution’ and hence the need for ‘the development of African answers to African problems’ (Young 1990:119).

But recent evidence shows that perceptions shared by local landscape architects suggest an enduring, and overwhelming ‘Eurocentric’ influence on the local profession, and products of landscape architecture (Shand, 2022; Shand & Breed, 2024).

… we were schooled in a very Eurocentric system of the designer acting on behalf of the community and not for the community, or empowering, or assisting them to get to a product […] I’ll come back to that very Eurocentric way of us saying… if you look at any book out there on landscape architects… Peter Walker’s design, or Halprin, or whoever, the West 8, whatever the case might be. Whereas it needs to be for the community. So, the first thing is how do we develop it for the community and understand the community… [Landscape architect interviewee 8, round 1, 2018].

…it is incredibly intimidating, because landscape architecture, does feel like a ‘white profession’ […] because people of different races don’t feel comfortable, sharing their concerns [Landscape architect interviewee 7, round 1, 2018].

Furthermore, while calling for an ‘Afrocentric approach’, certainly seems to oppose the centring of Eurocentric ideals, it does not necessarily translate to design informants that can have a tangible impact on local landscapes. For one, the homogenisation of African cultures and realities under one umbrella could be considered reductive, and ultimately unhelpful in addressing issues of African identity, especially given that the African continent is a complex make-up of vast and varying geographies, micro-climates, urban and rural conditions, and cultural groups – which is evident even across the country of South Africa.

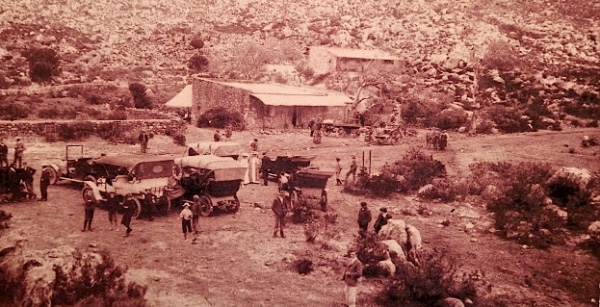

Additionally, there is also the problematic tendency towards an oversimplified binary relationship between Afrocentricism and Eurocentricism – placing them as antithetical to each other. But the reality in South Africa is that there are inextricable relationships between these ‘world views’ and their spatial manifestations, especially given the colonial influences in the country, and the impact they have had on people’s preferences and aspirations, which are not always as simple as rejecting one in favour of another.

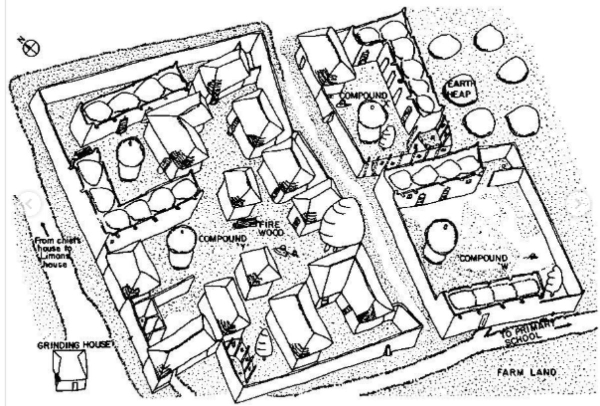

Many South African landscapes, including both the urban centres, and rural settlements have become an eclectic make up of styles, levels of affluence, and grades of informality.

Thus, it becomes a complex question to ask who, or what conditions, can be considered ‘African’ or not (Shand & Breed, 2025: 63), and what stylistic, functional, or spatial informants might be most appropriate in any given context. Moreover, authors such as Ekpo & Sidogi (2021) suggest that the sentimental “primitivising” and homogenisation of African culture, as a superficial response to the drive for ‘Afrocentricism’, is more detrimental than helpful in promoting the rights, needs and identities of African people and cultures. Thus, despite the value of vernacular and traditional architecture and place-making in South Africa, there are also a multitude of contemporary ‘African’ realities and informants that should also be considered, including levels of informality, gendered and generational roles and use of space, and contemporary aspirations (Shand & Breed, 2025). Thus, requiring a much broader and comprehensive gathering of stories about, preferences for, and observations of, South African rural and urban landscapes.

An argument for the role of ‘design reference material’ in promoting more just landscapes

Valuable literature on landscape architecture in South Africa exists in the form of the South African Landscape Architecture Reader (Stoffberg et al., 2012), and a number of articles including those by Breed et al. (2015) Breed (2022), Müller (2008) and, Young & Vosloo (2020), to name a few, that deal with critical and topical issues relating to South African landscape architecture. However, none of these are an encyclopaedic record of the typologies, features, characteristics and artefacts of local landscapes and landscape architecture in South Africa.

Additionally, while they are written with South African communities in mind, there is limited, direct inclusion, of community voices and knowledge. In short, there is, at present, a lack of comprehensive reference material on local South African landscape architecture that takes a historically, culturally and aesthetically inclusive perspective on local landscapes and landscape architectural artefacts. Given the diversity of languages, cultural backgrounds, geographic locales, and the diversity of vegetation, climates, and landscapes in the country – it is no wonder that such a resource does not exist. Yet, such a project has been undertaken for the profession of Architecture in South Africa – see Frescura & Myeza (2016) – which lists and illustrates a multitude of terms and illustrative records relating to the architectural and rural building traditions in South Africa. A similar undertaking could prove invaluable to local landscape architects and researchers.

Towards the development of a lexicon

As a multi-year, multi-faceted project, this study takes a pragmatic approach to the collection and analysis of relevant data. Including both fieldwork, and desktop studies – the data ranges from stories that people tell about their local, and home, landscapes; to academic articles and design reports that illustrate trends in public space design in South Africa. To date, interviews and observations have been carried out by the author, as well as a team of students (led by the author), in a variety of parks, highlighting both problems with local public open spaces, and the valuable relationships that communities hold with the landscape, and nature. Additionally, through a content analysis, the author and students have begun to collect and analyse both academic articles and design reports from various books and other resources that illustrate South African public, and open, spaces. Most recently, the main researcher (author) has also begun to mobilise data collection in the rural landscapes of Mpumalanga.

.jpg)

The significance of language

Given the ultimate and long-term goal of developing a truly representative lexicon of South African terms and imagery linked to the South African landscape, especially beyond the professional realm, the language of data collection matters.

“Today language is viewed as an important manifestation of culture, and its teaching is seldom conducted in isolation of other aspects of human activity. For this reason then, the architecture of a people cannot be read only in a strictly technical sense, but must also be part of a larger narrative involving aspects of their spiritual values, social mores, and material culture. One of the most important of these is their spoken language, and the symbolism attached to their nomenclature…” (Frescura & Myeza, 2016: introduction).

This reality has become increasingly evident in the collection of stories in local South African languages such as isiZulu, especially as participants become notably more animated in their conversations, and share much richer and nuanced stories. The insights into Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) in relation to the landscape and human-nature relationships captured in recent isiZulu interviews focused on the rural landscapes of Mpumalanga, far surpass the previous interviews collected primarily in English, and in relation to urban settings. But, it must be noted that in collecting such data, the translation and interpretation of stories and local knowledge will require a much more collaborative and iterative process, as different words can have different meanings in different languages and in different contexts. So, while language matters, so does the collaborative nature of such a project.

The inclusion of ‘Landscapes of Home’

Through stories collected in the urban setting of the City of Tshwane (as part of the pilot study) – it became increasingly evident that although many urban residents experience dissonance with their local urban landscapes, they resonated strongly with imagery from rural settings, and often shared stories about the broader South African landscapes and rural areas – including childhood memories, and the significance of certain landscape typologies and features for cultural, communal or spiritual activities. These preliminary findings have meant that the study areas cannot be limited to urban settings across the country, but must include rural landscapes, and a diversity of landscape typologies. The following examples expand on this point.

During one interview, a participant responded that an image of a park with generic steel play equipment, was, to him, symbolic of the apartheid era and ultimately reminded him of landscapes that were not designed for him. While in other interviews ‘play related to the landscape’ was described as far more integrated with the natural, undesigned landscape, and included elements of risk, and communal use.

“… where the dam starts. There’s a mountain and a river, so we used to climb on top of that mountain. We jump inside the water, even though it was dangerous, but it was nice. [laughs]. You know and my grandmother always… yelling at us for doing that, but I… I love it […] Even now when I’m grown up, I’m doing it. (Interview 8 (male), Burgers Park, 2024).

.jpg)

Linked to other collected stories, it must also be noted that some relationships to, and uses of, the rural landscape cannot easily be transferred to, or perhaps should not be interpreted within the urban setting – as some are tied to specific places (eg. large natural water bodies, or mountains) and their characteristics or histories (Cocks et al., 2016). The story featured below illustrates one such instance.

“Sometimes I do visit the bushes, especially where there’s ant holes. That is our way of connecting to the ancestors… it’s mostly the bushes and the rivers only… Whenever I feel bad I just go there and I speak my heart out because I prefer being alone most of the time. So that’s the only place I get… peace I guess.. […] It’s mostly away from the noise, away from town or anything like that. Anywhere where there’s tall trees or there’s grass where you can access ant holes…” (Interview 7 (female), Burgers Park, 2024).

.jpg)

The first story highlights the significance of natural, and rural landscapes, and can be interpreted to give insight into design language, features and informants that can be incorporated into local landscape designs. However, instances such as the second story will ultimately mean that what is included in an eventual repository or lexicon will have to be carefully, collaboratively and iteratively considered, so as to be as authentically representative, and as culturally sensitive as possible. It also means that some stories and human-nature relationships can more easily be translated into a graphic and textual lexicon, that may eventually have a tangible influence the design of public spaces – while others might simply serve to sensitise and transform the practice of landscape architecture to respond to a broader set of cultural values and lived realities.

Concluding thoughts

The ‘Storying the Landscape’ project is ongoing and will likely evolve as it gathers momentum, and is impacted by collaborations and input from the broader South African, and African, landscape community. Such collaborations and input are welcomed. In the meantime, the project contributors (the author, and students at the University of Pretoria) continue to collect stories, observe landscapes, and analyse existing reports, literature and case studies, with the ultimate goal to present a comprehensive insight into local landscape architectural practice, and the informants that can assist in the transformation of the local profession and products of landscape architecture. As the project evolves, lessons and outcomes, such as the significance of rural landscapes to South African residents, and the significance of language will continue to inform, and enhance the project and its ultimate outcomes.

References

Breed, C.A., (2022). Value negotiation and professional self-regulation – Environmental concern in the design of the built environment. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127626.

Breed, C.A., Cilliers, S.S. & Fisher, R.C. (2015). Role of landscape designers in promoting a balanced approach to green infrastructure. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 141(3). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000248

Chawane, M. (2016). ’The development of Afrocentricity: A historical survey’, Yesterday & Today Journal for History Education in South Africa and abroad, 16. doi:10.17159/2223-0386/2016/n16a5

Cocks, M., Alexander, J., Mogano, L. & Vetter, S. (2016). Ways of belonging: Meanings of “nature” among Xhosa-speaking township residents in South Africa. Journal of Ethnobiology, 36(4), 820 – 841. http://dx.doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-36.4.820

De Kock, M. (2024). Interrogating the potential for incorporating botanical knowledge and values into contemporary City of Tshwane public parks. [Unpublished masters mini-dissertation, University of Pretoria]. http://hdl.handle.net/2263/99906

Frescura, F., Myeza, P. J. and Frescura, F. (2016) Illustrated glossary of Southern African architectural terms, English-isiZulu : an illustrated survey of historical terms appertaining to the indigenous, folk and colonial architectures of Southern Africa. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press

Landman, K. & Makakavhule, K. (2021). Decolonizing public space in South Africa: From conceptualization to actualization. Journal of Urban Design, 26(5), 541 – 555. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2021.1880885

Mabaso, S. (2024). Landscape Narratives: Utilising Indigenous people’s stories to inform decolonized landscape design approaches. [Unpublished masters mini-dissertation, University of Pretoria].

Makakavhule, K. & Landman. K., (2020). Towards deliberative democracy through the democratic governance and design of public spaces in the South African capital city, Tshwane. Urban Design International, 25, 280 – 292. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-020-00131-9

Müller, L. 2008. Intangible and tangible landscapes: an anthropological perspective based on two South African Case Studies. South African Journal of Art History (SAJAH), 23( 1)118–138

Shackleton, C.M. & Gwedla, N. (2021). The legacy effects of colonial and apartheid imprints on urban greening in South Africa: Spaces, species, and suitability. Front. Ecol. Evol, 8(13). https://doi.org./10.3389/fevo.2020.579813

Shand, D.L., 2022. Nature-based park making: Interpreting nearby nature narratives to promote environmental justice in City of Tshwane Parks. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria]. https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/89688

Shand, D. L., & Breed, C. A. (2024). Latent potential? Searching for environmental justice in South African landscape architecture praxis. Landscape Research, 49(4), 457–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2024.2322133

Shand, D. L., & Breed, C. (2025). Knowing urban nature differently: undervalued nature relationships linked to community parks in the City of Tshwane. International Planning Studies, 30(1–2), 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2025.2465762

Stoffberg, H., Hindes, C. N. and Müller, L. (2012) South African landscape architecture. 1st edn. Pretoria: Unisa Press.

Young, G.A. 1990. ‘An Overview of Landscape Architecture in South Africa’, Aesthetic and Functional Values in Landscape Design Symposium, Athens, Greece, 23-26 September 1988. Panhellenic Association of Landscape Architects and Hellenic Society for Aesthetics. Pp 119 - 130.

Young, G., & Vosloo, P. (2020). Isivivane, Freedom Park: A critical analysis of the relationship between commemoration, meaning and landscape design in post-apartheid South Africa. Acta Structilia, 27(1), 85. 10.18820/24150487/as27i1.4