Heritage-Sensitive Urban Development at Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove

Les pressions urbaines menacent l’intégrité du bois sacré d’Osun-Osogbo, site du patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO au Nigéria. Cet article passe de la rhétorique à la réglementation, en présentant un cadre stratégique, africain et culturellement sensible pour la protection des zones tampons. Historiquement, la logique spatiale yoruba plaçait les bois sacrés au cœur des établissements humains. Les limites étaient maintenues non pas par des clôtures physiques, mais par des savoirs tacites, des tabous et une gestion communautaire qui ont préservé l’authenticité du bois sacré pendant des siècles. Aujourd’hui, l’urbanisation incontrôlée et l’érosion des connaissances traditionnelles ont conduit à une forte emprise sur la zone tampon.

En réponse, l’article présente l’Initiative de développement urbain sensible au patrimoine, une réforme systémique qui intègre les logiques spatiales indigènes dans la planification urbaine contemporaine. L’initiative prévoit des audits spatiaux basés sur les SIG, des codes de construction co-conçus et l’intégration du plan de gestion de la conservation du site dans la réglementation urbaine de l’État. Osun-Osogbo est présenté comme un modèle reproductible pour la protection des paysages sacrés africains. L’article soutient que la conservation efficace nécessite l’adaptation des modes de gouvernance indigènes et des savoirs tacites aux politiques modernes, offrant ainsi une approche africaine authentique de la gestion du patrimoine et de l’aménagement paysager.

En analysant cette initiative à travers le thème de la conférence ILASA–IFLA Afrique, « Repenser le paysage africain », l’article démontre comment une réglementation sensible au patrimoine peut produire des résultats mesurables. Dans l’État d’Osun, cette approche est actuellement mise en œuvre à travers un programme pilote de cartographie SIG et un cadre de zonage révisé, visant une réduction de 30 % de l’empiètement et la création de 500 emplois liés au patrimoine d’ici 2026 — une voie concrète vers l’intégration de l’intégrité culturelle dans la gouvernance urbaine.

Urban pressures are threatening the integrity of Nigeria’s Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This paper moves from rhetoric to regulation, outlining a strategic, African-led framework for culturally sensitive buffer zone protection. Historically, Yoruba spatial logic placed sacred groves at the centre of settlements. Boundaries were maintained not by physical fences but by tacit knowledge, taboos, and community custodianship that safeguarded the grove’s authenticity for centuries. Today, unchecked urbanisation and the erosion of traditional knowledge have led to significant buffer-zone encroachment. In response, the paper introduces the Heritage-Sensitive Urban Development Initiative, a systemic reform that integrates indigenous spatial logic into contemporary urban planning. The initiative mandates Global Information Systems-based spatial audits, co-designed building codes, and embeds the site’s Conservation Management Plan into state-level regulation. Osun-Osogbo is positioned as a replicable model for protecting Africa’s sacred landscapes. The paper argues that effective conservation requires adapting indigenous governance and tacit knowledge into modern policy, offering an authentic African approach to heritage management and landscape planning. By analysing this initiative through the lens of the ILASA–IFLA Africa Conference theme, “Reframing the African Landscape,” the paper demonstrates how heritage-sensitive regulation can generate measurable outcomes. In Osun State, this approach is now being operationalised through a pilot GIS mapping programme and a revised zoning framework aimed at achieving a 30% reduction in encroachment and the creation of 500 heritage-based jobs by 2026, a tangible pathway toward embedding cultural integrity within urban governance. Keywords: Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove, buffer zones, Yoruba planning models, heritage-sensitive planning, community-led governance

Introduction

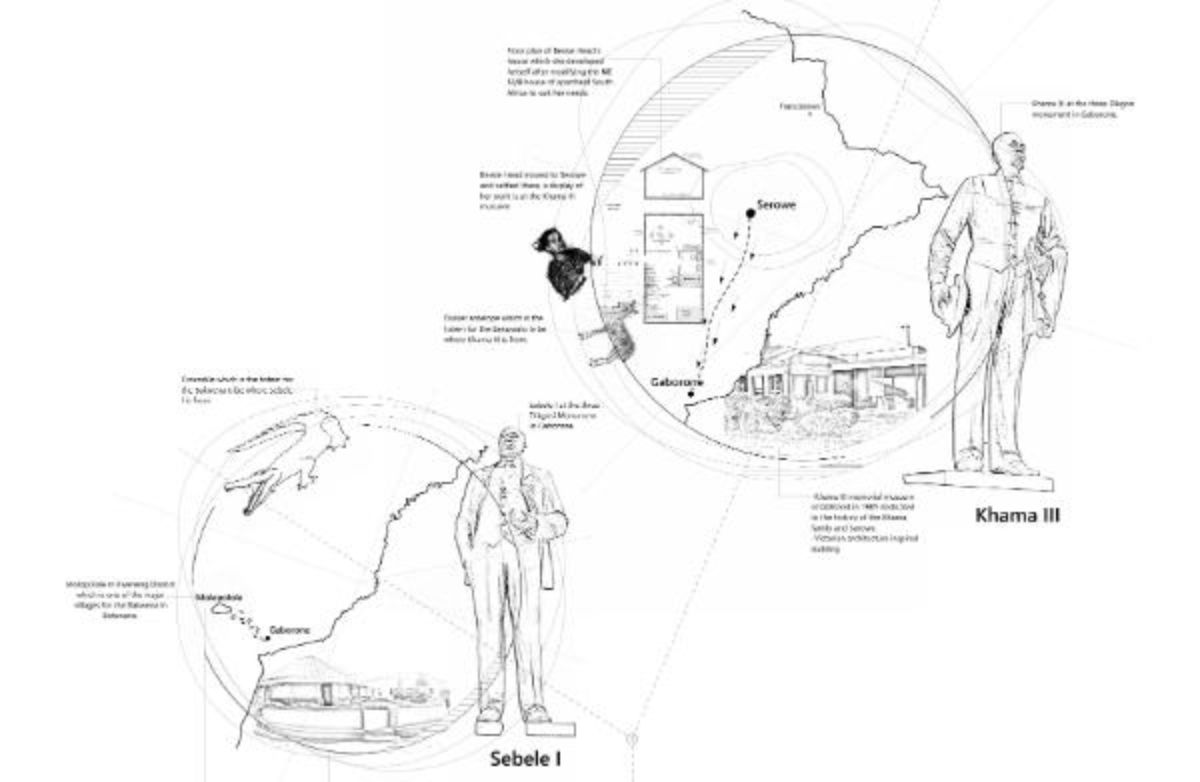

The theme “Reframing the African Landscape” challenges scholars and practitioners to move beyond Eurocentric paradigms of planning, heritage and education. Too often, imported models neglect indigenous knowledge systems, socio-cultural contexts, and African ecologies (Kombe & Kreibich, 2006). Sacred groves such as Osun-Osogbo demonstrate that African landscapes are not passive spaces but active cultural and spiritual ecologies.

This article explores how Osun-Osogbo can inform new approaches to heritage-sensitive urbanism. It frames the Grove not simply as a UNESCO World Heritage Site but as an exemplar of Yoruba planning philosophy—one that placed sacred spaces at the core of settlements. By introducing the Heritage-Sensitive Urban Development Initiative, the article argues for a regulatory model that fuses indigenous governance with contemporary planning law.

Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove in Context

The Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2005 under criteria (ii), (iii), (vi), recognising its significance as a living cultural landscape (UNESCO, 2005). It encompasses shrines, sculptures, river systems, and forested areas dedicated to the goddess Òsun. For centuries, its sanctity was upheld by Yoruba cosmology, where groves symbolised the interconnection between humans, ancestors, and deities (Drewal, 1992).

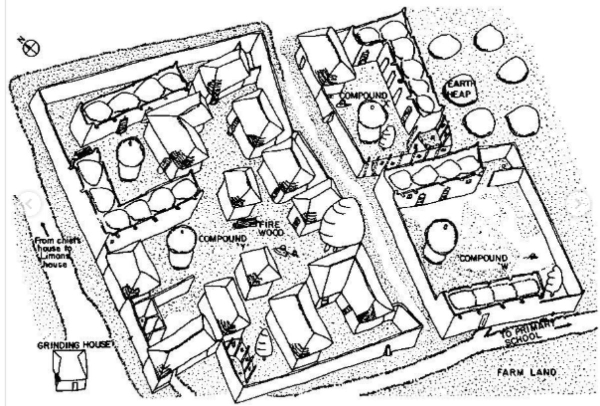

Unlike fenced reserves, Yoruba sacred landscapes relied on intangible governance: community custodianship, spiritual taboos, and oral transmission of knowledge (Johnson, 2021). This logic ensured ecological sustainability and cultural continuity. However, with colonial disruption, missionary activity, and post-independence urbanisation, these governance systems weakened, exposing the Grove to encroachment.

Urbanisation Pressures and the Limits of Eurocentric Planning

Osun State has experienced rapid urban growth since the 1990s, driven by demographic expansion and land speculation. Consequences include:

• Encroachment into buffer zones, undermining the Grove’s ecological resilience.

• Loss of vernacular architecture and settlement patterns.

• Decline of tacit custodial practices as younger generations adopt alternative livelihoods.

Conventional planning frameworks in Nigeria, inherited from colonial models, often classify sacred groves as undeveloped land. This misrecognition prioritises infrastructure and real estate over cultural landscapes (Agboola & Zango, 2014). Eurocentric approaches to buffer zones, based on rigid zoning, fail to capture the fluid and spiritual dimensions of Yoruba space.

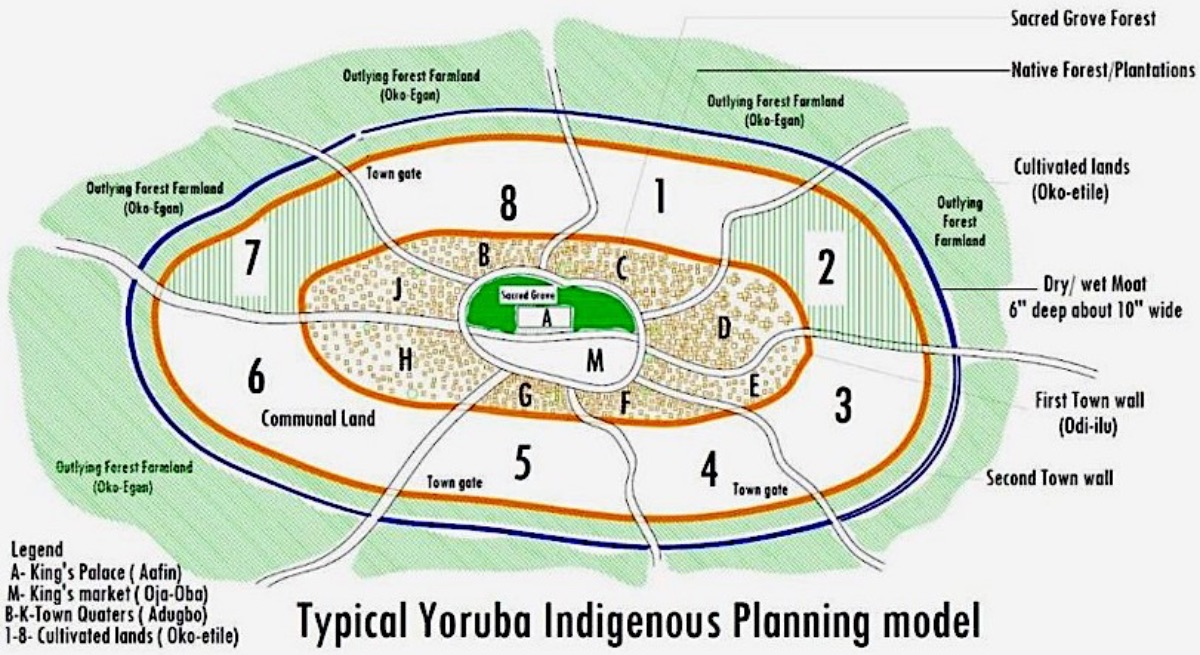

Yoruba Spatial Logic: An Indigenous Planning Model

Yoruba spatial philosophy provides an important theoretical counterpoint to Eurocentric models of planning and heritage conservation. Unlike Western land-use planning, which tends to separate functions and define strict territorial boundaries (Hall, 2002), Yoruba spatial logic is relational and processual. Space is not an abstract geometric container but a lived and spiritual entity, continually constituted through rituals, taboos, and social practice (Akintoye, 2010).

Central to this is the concept of ase—the vital force or authority that animates both human and non-human actors (Drewal, 1992). Within this cosmology, sacred groves were not marginal spaces to be set aside, but central nodes in the socio-spatial fabric. Their sanctity derived from shared understandings transmitted orally and reinforced through ritual. In this way, Yoruba planning operated through what Lefebvre (1991) might call “representational spaces”—spaces lived and imbued with symbolic meanings—rather than abstract zoning maps.

Boundaries, therefore, were not demarcated by physical fences but by tacit codes:

• Taboos that restricted resource extraction and harmful activities.

• Custodial vigilance rooted in community responsibility.

• Embodied ritual practices that continually re-affirmed the sacred status of the grove.

This model also aligns with theories of “intangible governance” (Nara, 2019), where spatial order is maintained not through written regulations but through cultural performance and shared belief systems. The loss of these tacit systems under colonial and postcolonial disruptions underscores why modern conservation frameworks must recover and adapt them if they are to remain authentic to their cultural contexts.

Critical Comparisons with Western Buffer Zone Models

In contrast, Western planning approaches to buffer zones rely heavily on codified laws, mapped boundaries, and enforcement mechanisms such as physical fencing or policing. These frameworks, influenced by Enlightenment rationalism and Cartesian spatiality, conceptualise land as divisible, measurable, and subject to external control (Scott, 1998). In practice, they often prioritise conservation through exclusion, separating “protected” areas from lived human landscapes.

While this rigidity can be effective in contexts where legal authority is respected and enforceable, it risks alienating local communities by disregarding their spiritual and cultural relationships to land (Adams & Hutton, 2007). Moreover, buffer zones in UNESCO frameworks are frequently understood as technical instruments rather than lived cultural spaces, which can reduce heritage to material form while neglecting intangible practices.

By contrast, Yoruba spatial governance emphasised relationality, community agency, and tacit knowledge. Rather than enforcing protection from the outside, sacred groves were safeguarded from within, through shared belief in the consequences of transgression. This illustrates a profound epistemological difference: where Western models privilege control, Yoruba logic privilege consensus; where zoning maps prescribe, Yoruba practice performs; where regulations are codified, Yoruba norms are embodied.

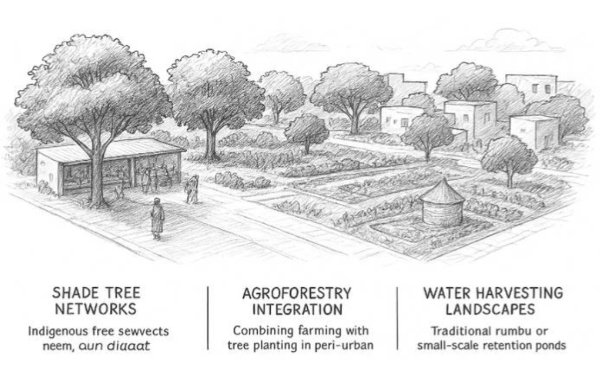

In reframing African landscapes, this comparison highlights the need for hybrid models. Yoruba governance offers resilience, legitimacy and cultural continuity, while modern planning tools (e.g., GIS monitoring, legal enforcement) can address contemporary pressures. The challenge—and opportunity—lies in combining them to create a regulatory framework that is both culturally authentic and practically enforceable.

The Heritage-Sensitive Urban Development Initiative

The Heritage-Sensitive Urban Development Initiative (HSUDI) in Osun State aims to respond to these challenges by embedding indigenous governance into statutory planning. Its components include:

• GIS-based spatial audits to track encroachment and visualise change.

• Revised zoning laws protecting sacred groves as living cultural landscapes rather than vacant land.

• Community-led building codes, co-designed with traditional custodians to align with Yoruba aesthetics.

• Mandatory Heritage Impact Assessments (HIAs) for all developments within proximity to sacred landscapes.

• Integration of Conservation Management Plans (CMPs) into state-level planning law.

By operationalising Yoruba custodial traditions, HSUDI bridges intangible governance with enforceable planning.

Reframing Through Education, Practice, and Futures

Reframing Through Education

Landscape education in Africa has long been dominated by Global North curricula, privileging Western planning, design theory, and ecological frameworks (Omisore, 2018). This epistemic dependency perpetuates what Santos (2014) terms “epistemologies of the North,” in which knowledge systems from the Global South are rendered invisible or marginal.

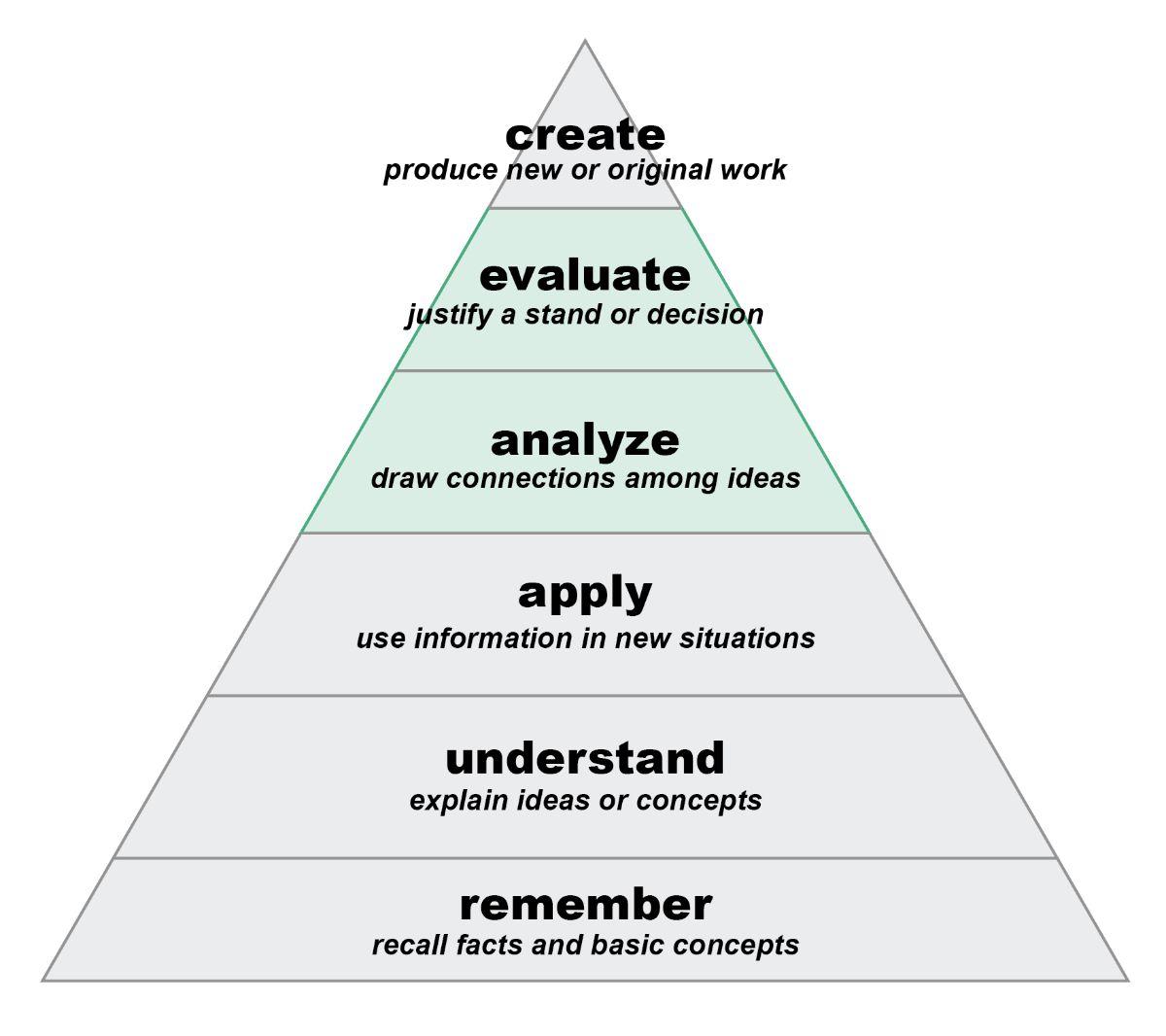

To reframe education, it is necessary to integrate indigenous epistemologies—such as Yoruba spatial logic—into the teaching of planning and landscape architecture (Adejumo, 2011). This is not only about adding case studies but about shifting the theoretical foundations of curricula. For instance:

• Decolonial Pedagogy: Following Mbembe (2016), curricula should unsettle colonial epistemic hierarchies and foreground African modes of spatial reasoning as legitimate sources of theory, not just folklore.

• Tacit Knowledge Transmission: As Polanyi (1966) argued, not all knowledge is codified. Yoruba spatial practices show how tacit and embodied knowledge can be pedagogically transmitted through storytelling, ritual observation and community immersion.

• Plural Ecologies of Knowledge: Rather than privileging Western ecological science alone, landscape education should cultivate what Escobar (2018) calls “pluriversal design,” acknowledging the coexistence of multiple ontologies of land and space

Reframing education in this way aligns with Freire’s (1970) notion of a pedagogy of the oppressed, where learners are not passive recipients of foreign models, but active co-creators of knowledge rooted in their cultural contexts. The Osun-Osogbo case offers a pedagogical model for how heritage-sensitive urbanism can be taught not only as a technical skill but as a critical engagement with identity, belonging and epistemic justice.

Reframing Through Practice

Professional practice in landscape architecture and planning has too often mirrored Western conservation paradigms that privilege control, codification, and exclusion (Adams & Hutton, 2007). Sacred groves are frequently treated as ecological reserves or cultural monuments, separated from living communities and managed through technocratic frameworks.

Reframing practice requires moving toward what Healey (1997) calls “collaborative planning,” where decision-making is embedded in networks of actors, including local custodians and knowledge bearers. In African contexts, this means recognising the legitimacy of traditional custodians as co-managers of heritage landscapes, rather than viewing them as stakeholders to be consulted after the fact.

The Heritage-Sensitive Urban Development Initiative exemplifies this reframing. By integrating community-led building codes and Yoruba aesthetics into planning regulation, it reflects what Porter (2010) terms “indigenous planning”: practice that challenges dominant systems of property, law and authority by embedding indigenous worldviews. In doing so, it reframes conservation not as a restrictive exercise but as an enabling practice that sustains cultural identity, ecological resilience, and socio-economic vitality simultaneously.

Reframing Imagined Futures

Reframing is not only about critique but also about generating alternative futures. Osun-Osogbo demonstrates how heritage-sensitive planning can move beyond preservation to become a platform for sustainability and social justice.

This resonates with theories of “anticipatory governance” (Boyd et al., 2015), which argue for planning that is forward-looking, adaptive, and responsive to multiple futures. It also aligns with Escobar’s (2018) call for “pluriversal futures”, in which diverse ontologies of land, spirituality and community co-exist and co-produce space.

The measurable targets of the Initiative—such as a 30% reduction in encroachment and the creation of 500 heritage-based jobs by 2026—illustrate how heritage can be positioned as an engine for local livelihoods, climate resilience, and inclusive urbanism. Rather than treating sacred groves as relics of the past, reframing futures positions them as active laboratories for just and sustainable African urbanism.

This vision challenges what Yusoff (2018) critiques as the “colonial Anthropocene,” where landscapes are imagined primarily through extractive and developmental logics. Instead, Osun-Osogbo offers a decolonial Anthropocene, one in which cultural landscapes are revalued as infrastructures of care, resilience, and pluriversal imagination.

Conclusion

The Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove exemplifies the urgency of reframing African landscapes. Conservation cannot remain descriptive or preservationist; it must be systemic, critical, and generative.

The Heritage-Sensitive Urban Development Initiative demonstrates how Yoruba epistemologies can be translated into regulation, bridging indigenous governance with modern planning.

This model challenges Eurocentric paradigms, contributes to the theory of decolonial practice, and positions African heritage as a driver of sustainable urban futures. Moving from rhetoric to regulation, Osun-Osogbo is not only a case study but also an invitation to reimagine conservation as an authentically African act.

References

Adejumo, O.T. (2019) Canvas of Civilization. Lagos: University of Lagos Press.

Agboola, T. and Zango, M.S. (2014) ‘Housing and urban development in Nigeria: A critical perspective’, Journal of the Nigerian Institute of Town Planners, 22(2), pp.15–32.

Akinmoladun, O. and Adejumo, T. (2011) ‘Traditional Yoruba settlements and environmental sustainability’, Nigerian Journal of Environmental Design and Management, 4(1), pp. 44–59.

Akintoye, S.A. (2010) A History of the Yoruba People. Dakar: Amalion Publishing.

Adams, W. and Hutton, J. (2007) ‘People, parks and poverty: Political ecology and biodiversity conservation’, Conservation and Society, 5(2), pp. 147–183.

Drewal, H.J. (1992) Yoruba Ritual: Performers, Play, Agency. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Escobar, A. (2018) Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

Hall, P. (2002) Urban and Regional Planning. London: Routledge.

Johnson, M. (2021) ‘Yoruba indigenous planning models’, African Journal of Landscape Architecture, 3(2), pp. 27–41.

Kombe, W. and Kreibich, V. (2006) Urban Land Management in Africa: Towards Sustainable Land Use. Berlin: Springer.

Lefebvre, H. (1991) The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Mbembe, A. (2016) ‘Decolonizing the university: New directions’, Arts & Humanities in Higher Education, 15(1), pp. 29–45.

Nara, R. (2019) ‘Intangible governance in African heritage landscapes’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(7), pp. 845–860.

Omisore, E.O. (2018) ‘Landscape architecture in Nigeria: Educational challenges and opportunities’, Journal of African Built Environment Research, 7(3), pp. 65–78.

Polanyi, M. (1966) The Tacit Dimension. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Santos, B. de S. (2014) Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. London: Routledge.

Scott, J.C. (1998) Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

UNESCO (2005) Nomination file: Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove. Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre.