Bronze Heroes and Plastic Memories: The Anti-monument in Gaborane, Botswana

Cet article remet en question l'utilisation de statues en bronze comme moyen de commémoration au monument Three Dikgosi et soutient que l'utilisation de statues dans la commémoration montre que le colonialisme est toujours ancré dans le contexte sud-africain, ce qui influence la façon dont ces espaces commémoratifs sont perçus.

L'« anti-monument » est un monument qui remet intentionnellement en question tous les principes d'un monument traditionnel. En explorant la notion de « vandalisme contrôlé », qui est utilisée dans cet article pour définir l'adaptation minutieuse des statues en vue d'un résultat spécifique, les statues actuelles sont soigneusement modifiées et enfouies dans un monticule de terre.

En outre, un nouveau rituel est introduit : lors des célébrations de la fête de l'indépendance, une procession partant de la rivière Segoditshane, au nord du site, aura lieu, au cours de laquelle les gens transporteront du sable et le placeront au sommet du monticule, finissant ainsi par enterrer ces statues et les effacer du paysage, ce qui devrait avoir lieu d'ici 2063. L'article conclut qu'à travers cet acte actif de commémoration, la communauté se voit donner le pouvoir de revendiquer non seulement son paysage, mais aussi son histoire et son identité, en effaçant activement les modes de commémoration coloniaux et en offrant aux habitants de Gaborone une option durable pour commémorer leur passé à l'avenir.

This paper questions the use of bronze statues as a way of memorialisation at the Three Dikgosi Monument and argues that the use of statues in memorialisation shows that colonialism is still embedded in the Southern African context, which affects how these memorial spaces are perceived. The ‘Anti Monument’ philosophy is one that intentionally challenges every principle of a traditional monument. By applying the notion of “Controlled Vandalism” which in this paper is coined to define the careful adaptation of statues for a specific outcome, the existing statues are carefully altered and submerged into an earth mound. Further, a new ritual is introduced where during Independence Day celebrations, a procession from the Segoditshane River North of the site would occur where people would carry some sand and place it atop the mound, thereby eventually burying these statues and erasing them from the landscape, which is estimated to take place by 2063. The paper concludes that through this active act of remembrance; power is given to the community to claim not only their landscape back, but also their narrative and purpose by actively erasing colonial ways of memorialisation. This act may also give the people of Gaborone a sustainable option in how they can memorialise for the future.

Introdcution and Theoretical Underpinning

“The struggle is over, so let’s polish it up and sell it.” Thuli Gamedze, (2015)

Thuli Gamedze, (2015

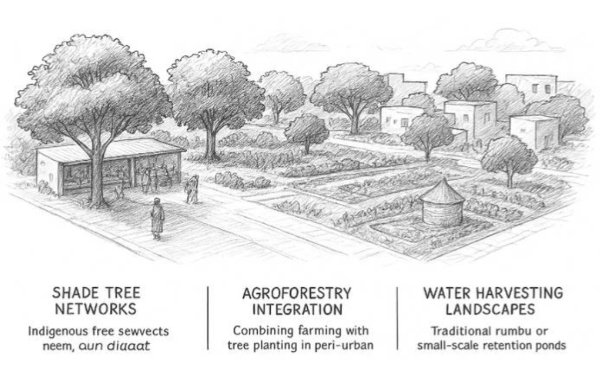

Are bronze statues an appropriate way of memorializing key individuals in post-colonial Africa or are they simply a borrowed idea from the colonialists? Considering that some of these edifices already exist within our landscape, how can we manipulate them to tell their story to the future communities whilst keeping in line sustainablility principles ? Sustainability in this context would be the ability to maintain and preserve the natural and social systems that support the cycle of life as described by Elyasi and Yamaçlı (2023).

This design thesis focuses on questioning the relevance of statues as memorials in post-colonial Gaborone in Botswana starting with the Three Dikgosi Monument (Figure 1)and questions the use of bronze statues as a way of memorialisation in this context. This paper argues the use of statues in memorialisation shows that colonialism is still embedded in the very way we commemorate and affects how these memorial spaces are perceived in public spaces.

Marschall (2017a, p. 675) notes how there is a disjuncture between existing monuments and how the public perceives them, especially in the context of the Southern region of Africa. She describes monuments as “edifices that try so hard to be noticed yet they virtually repel our gaze”.

This is most common with the younger generation as many of the youths are unable to engage with these statues because they have no meaning attached to them. Nettleton (2019, p. 51) argues that currently, monuments have lost their symbolic importance and are merely viewed as public sculptures which diminishes their importance in embodying past events and values. Gamedze (2015) also notes that statues are both a continuation of the pre-1994 iconography, because of how they have a similar aesthetic to their predecessors now with different figureheads. This paper also argues that bronze statues of past individuals is a somewhat watered-down method of representing public memory.

Nettleton (2019, p. 51) mentions that in commemorating key past figures, one does not have to indulge in the “neo-romantic realism” of bronze figure sculptures but should strive to achieve more thoughtful, context-centred, and community-inspired memorials than tired remakes of colonial prototypes, which is what this thesis attempts to do. Tafuri (1976:172) explains that the instruments of capitalist cover-ups—specifically, the ideological and aesthetic tools such as architecture and monumental art—are employed to conceal the exploitative realities inherent in capitalist production. These instruments serve to dazzle the public, effectively drawing attention away from underlying social and economic inequalities. Through this manipulation, the public is co-opted into accepting monuments as the universal languages of emancipation and progress. This phenomenon can be observed in the way monuments are presented within public spaces, shaping collective perceptions and reinforcing particular narratives while masking the complexities and contradictions of the systems they arise from. This is evident in the Three Dikgosi monument in Gaborone where a form of ‘nationalised identity’ has made people abandon their former ethnic and localised identities to a great extent.

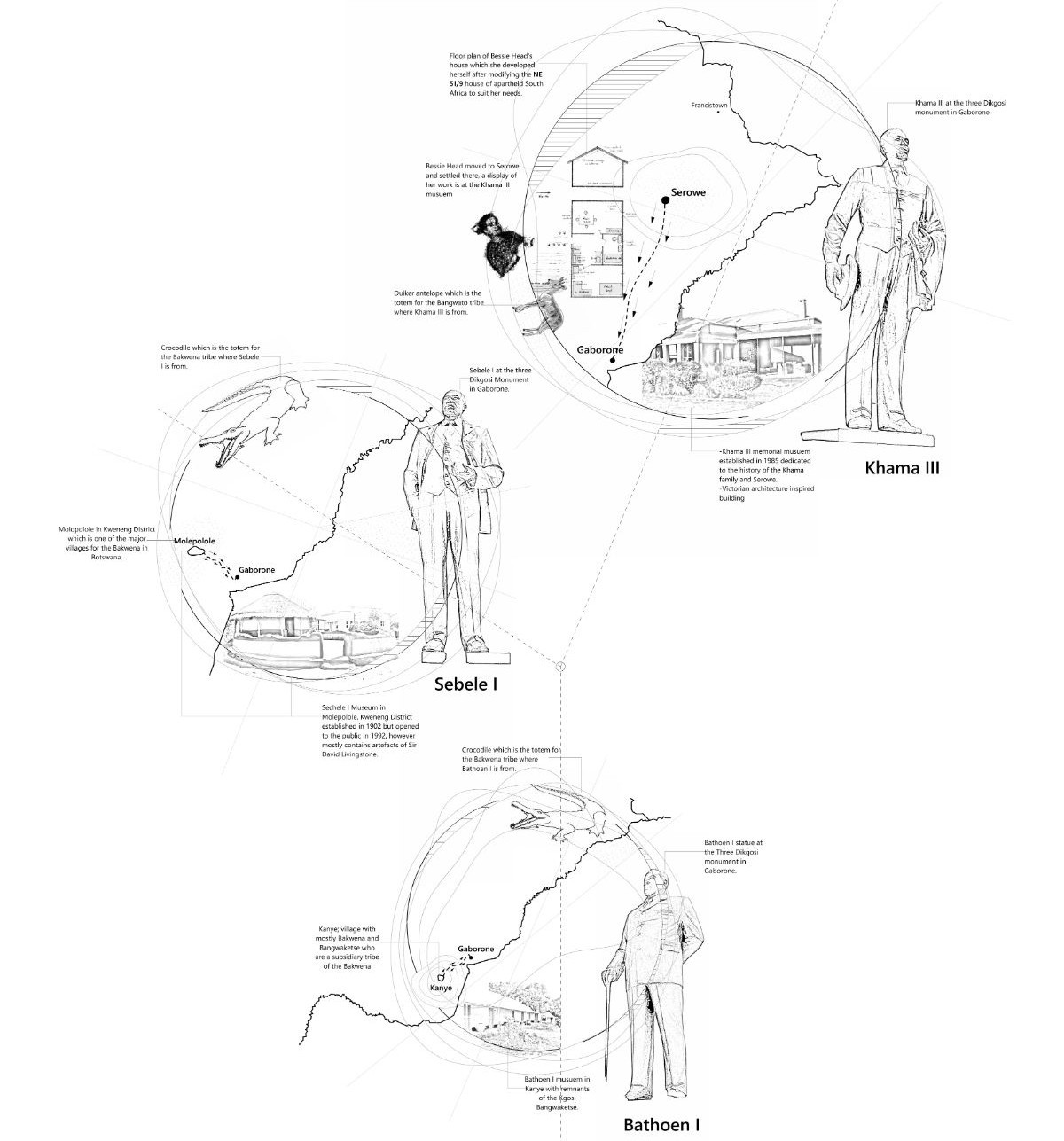

This research aims to discover alternative Southern African ways of memorialising in the urban landscape within the context of Gaborone and highlight specific ways of remembrance for the particular tribes involved. Through studying Catherine Dee’s Critical and Visual Studies Landscape research methods, this thesis will employ the use of “Visual Narratives” through poetry and “Dialogic Drawings” in the form of technical drawings. This is to emphasise as Dee (2004, p. 22) highlight's how places in the landscape are conceived and made and thereafter perceived and understood. In the “Visual Narratives” research method, Dee (2004, p. 22) explains the telling the stories of landscapes through narrative.

Stanley (2020) notes that statues and memorials are both largely unseen and also omnipresent aspects of urban landscapes. She adds that their presence adds value to the urban fabric in how they are understood, much as their specific histories may be misrepresented or poorly documented. This could be because of the lack of engagement with the public during the design and planning phase of these edifices.

Gamedze (2015) states that without re-imagining our public spaces, we are inevitably trapped by a linear history with a rotten origin, and bronze sculptures are simply a symptom of that.

She adds that “…Bronze symbolises a regime, a triumph over land. It spurs action within people who look at bronze figures and do not see themselves reflected back.” This demonstrates how by mimicking Western and Communist imagery, these statues are denied the right to cultural representation and memorialisation.

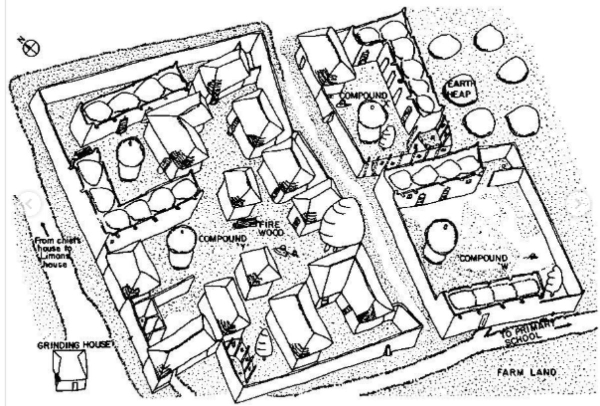

Since Botswana gained independence, its communities have been in a co-current and continuous dialogue with the past and present. Similar to South Africa, stories that were once buried and censored are becoming more central to an evolving public memorial and informative space as Judin (2021, p. 7) highlights. This is a positive sign in beginning to ‘decolonise’ spaces in Southern Africa. It is important for African countries to tell their narrative concerning its traumatic political past (Figure 2).

However, what happens when colonialism is embedded into the very thinking of its colonies in that the architecture that they now create continues to re-live its tyrants past? What happens when the statues designed are to resemble that of the oppressor and hence its very own people are unable to interact or engage with them? This leads to my final question; what would a space of memorialisation look like if it were a space that allowed the public to create and recreate its own formulations of memory?

Principles of Statue Design as Memorials

According to Antonova (2017), an urban design researcher, an urban monument can be considered, firstly, as an object of territorial orientation and secondly, as a semantic point with a value-symbolic content with which collective associations are formed. She further explains that the design principles governing monuments encompass scale, orientation, proportion, and materiality. Orientation refers to the monument’s spatial placement within its specific context and the axis along which it is aligned. Scale pertains to the monument’s relationship with its surroundings and the human body, as this is influenced by the viewer’s distance and angle of perception. Materiality concerns the choice of materials—particularly their durability and their symbolic significance within the community. These principles are illustrated in the drawing below in Figure 3.

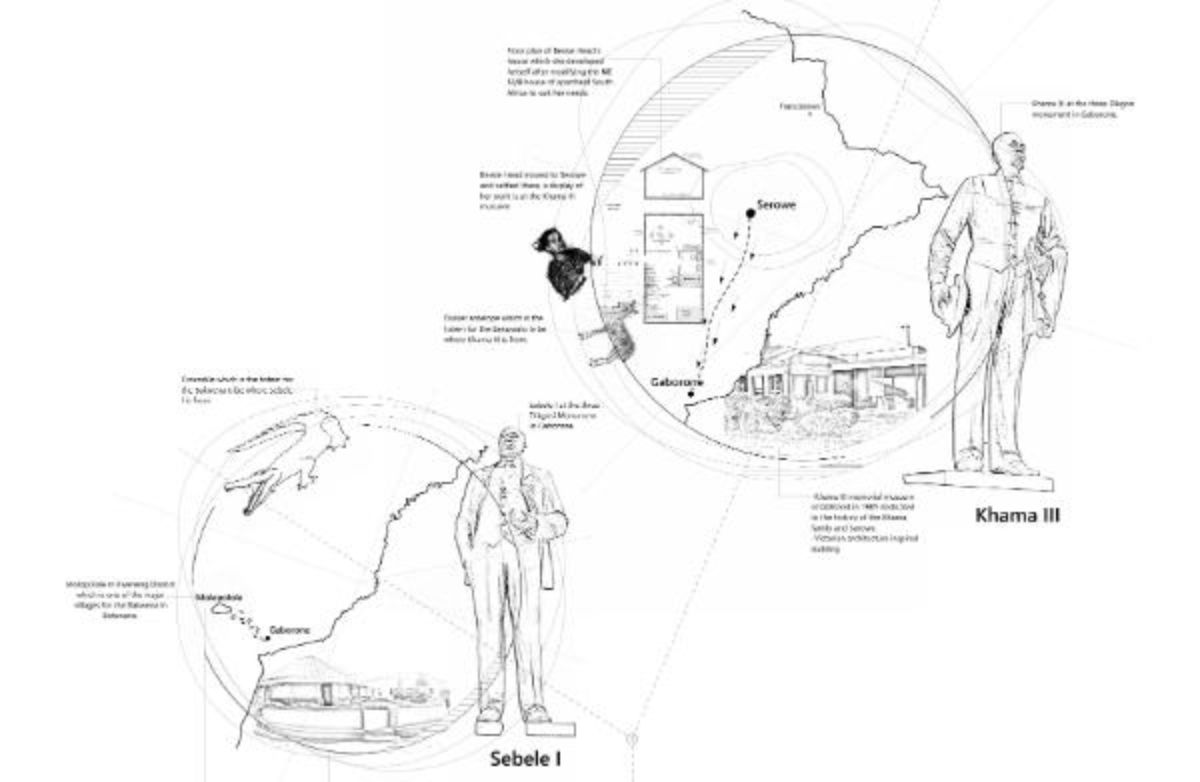

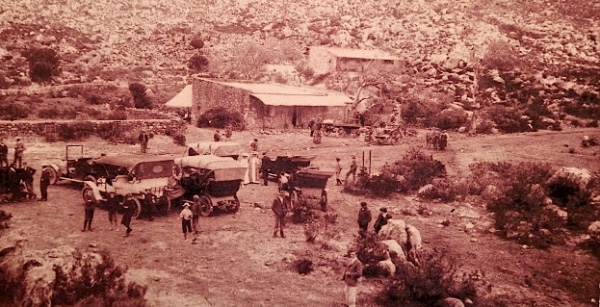

The Three Dikgosi Monument

The monument is a 5.4-metre tall bronze statue of three Dikgosi, or chiefs, who are said to have played important roles in Botswana’s independence: Khama III, Sebele I, and Bathoen. The three chiefs travelled to Great Britain in 1895 to ask Queen Victoria to separate the Bechuanaland Protectorate (Botswana pre-Independence) from Cecil Rhodes’s British South Africa Company and Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe). This resulted in Botswana becoming a British Protectorate.

The paper then uses these principles to interrogate the Three Dikgosi Statue and use their inverse as a basis to design the ‘Anti Monument’, which will counter each of the mentioned principles. The ‘Anti Monument’ is one that intentionally challenges every principle of a traditional monument.. The takeaway from these principles is how they would be incorporated into design, for instance scale does not have to be experienced vertically for it to be effective but could be experienced below ground as in the 9/11 Memorial. Employing the inverse of an established concept or system serves as a critical method for re-evaluating its underlying logic and function. Through inversion, the foundational assumptions that govern a concept are exposed, allowing for a deeper understanding of its internal structure and operational principles. This process not only challenges conventional modes of thinking but also expands the boundaries of interpretation by revealing alternative possibilities.

Intervention

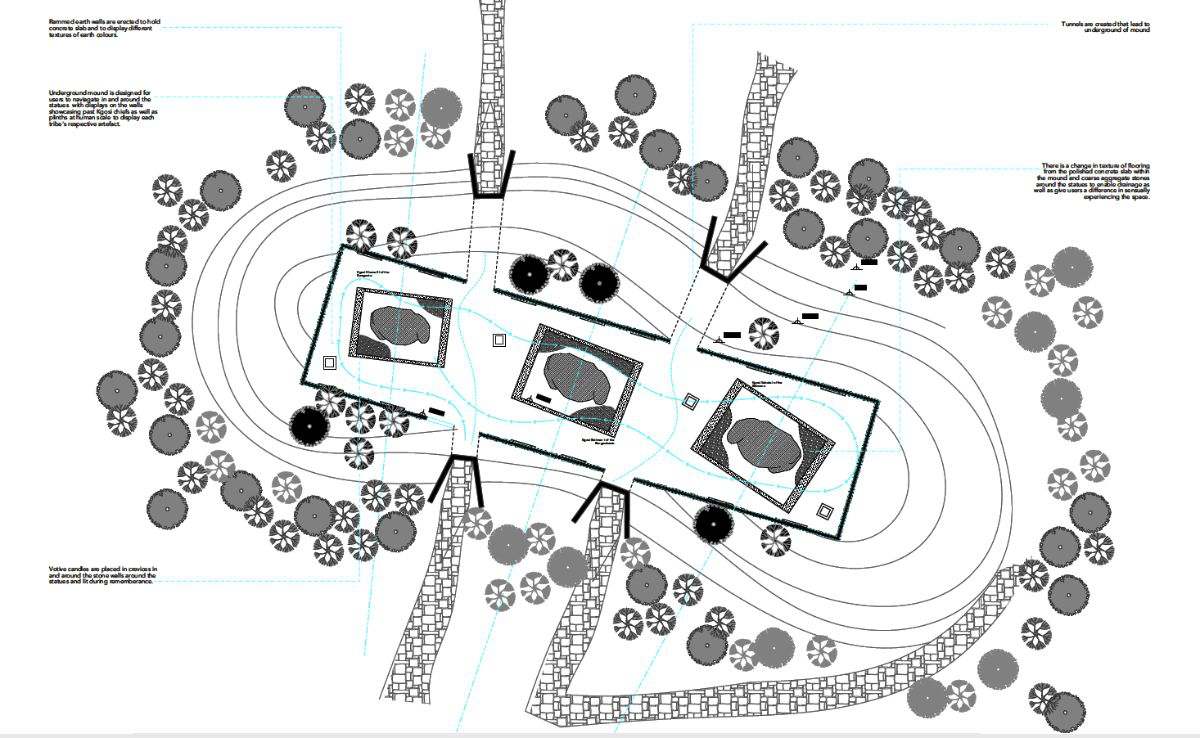

In the design proposal for the three Dikgosi Monument, the programme is defined by two major themes, “Arrival then Engage”. The site was first expanded to create a larger area for the earth works and a public green space within the City’s Core. Thereafter, through exploring the notion of Controlled Vandalism which Sabine Marschall a renowned author of Landscapes of memory writes about, the statues are carefully detached from their plinth and moved north on the site. The granite plinth base is centralized to act as a performance stage for the community. A green amphitheatre is proposed south of the site, right at the entrance, to also enhance community engagement. This is to connect it to the other proposed important points . Mounds of about 1.8m high are introduced into the site to break the monotony of the existing flat landscape and to act as a boundary without using a fence. Refer to Figure 4.

The Three Dikgosi are carefully turned to face south because it is said that in Tswana culture a chief will always face his community, then they are partially submerged into the main feature mound of the site as shown. The intention of submerging the statues is to carefully create the Anti-Monument by manipulating the space around these statues and not necessarily altering the bronze edifice itself (Figure 5). This takes inspiration from Tadao Ando’s Buddhist hill temple where a mound was created around the isolated Buddhist statue on a hill.

The bust of the statue is exposed and dressed in each Kgosi’s traditional attire to reflect respective tribes. This is to counter the fact that these statues were all built from templates of North Korean leaders and not in like of their true African leaders. This is even depicted in how the statues are dressed in modern day tailored suits (Figure 6). Atop the mound, people are to view these statues at human scale as opposed to the towering scale it currently sits at.

The bottom half of the statue is left in its colonial attire and left in the ground to represent that the past is buried. Tunnels made out of rammed earth are introduced into the mound for people to navigate around these statues with displays in different parts as shown. The statue is submerged surrounded by a retaining wall made out of stone rubble with crevices and nooks created for votive candles which the users light as they remember these chiefs. The statue submersions are not covered, and this is for people to fully experience the scale from both above and below which has different effects.

Lastly, as people walk up the mound to experience these statues, they will go with a rock or some soil to place on the mound, which draws inspiration from how people throw soil on graves during and after burial. It is intended to be a full event during Independence Day celebrations where people will have a procession beginning from the Segoditshane River North of the site and carry some sand from there whilst gradually proceeding to the Three Dikgosi site. They will go through the amphitheatre tunnel entrance and emerge through to the main feature mound where they will pour the soil on top.

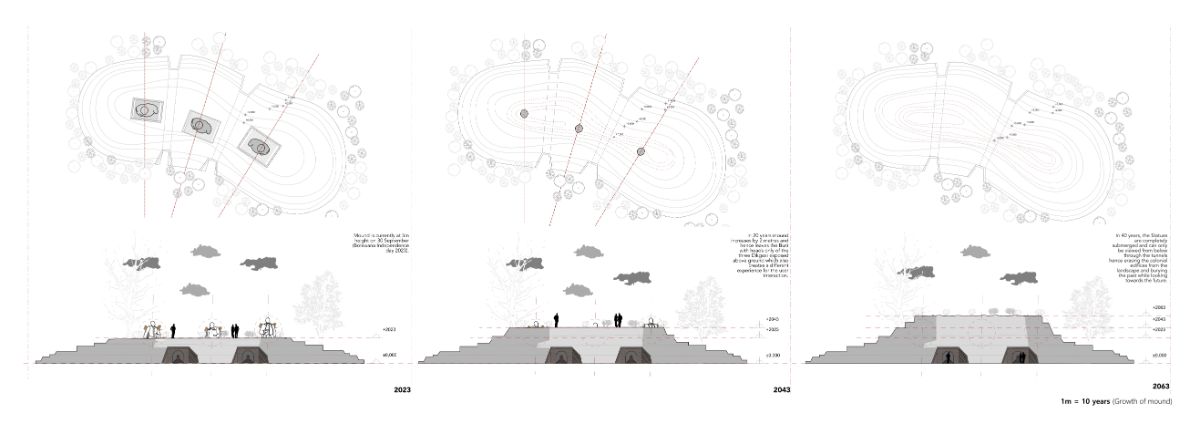

A scale of about 1m high for every 10 years that this event occurs is estimated and would be repeated every Independence Day. The mound would grow two metres high for every 20 years as shown in the drawings below and it is estimated that by 2063 the statues would be fully buried into the mound and only accessed through the tunnels underground (Figure 7). Through this active act of remembrance, power is given back to the community to reclaim not only their landscape, but also their narrative and purpose, and speaks to the future landscape of memory in Botswana.

Conclusion

This study questioned the relevance of bronze statues as a mode of memorialization in post-colonial Africa, using the Three Dikgosi Monument in Gaborone as a case study. It argues that such statues, though intended to commemorate, perpetuate colonial aesthetics and values by privileging permanence and hierarchy over participation and change.

The proposed Anti-Monument offers an alternative approach that reinterprets existing symbols rather than erasing them (Figure 8).

Through the concept of Controlled Vandalism, the intervention transforms the statues into dynamic elements of the landscape—objects to be engaged with, altered, and ultimately reabsorbed through communal ritual.

This gradual process of burial reflects a more sustainable and inclusive act of remembrance, where memory becomes fluid and participatory rather than fixed in form.

In doing so, the project redefines memorial spaces as evolving, community-driven narratives rather than static monuments. It suggests that the future of memorialisation in Southern Africa lies not in preserving bronze heroes, but in cultivating memories—flexible, temporal, and rooted in the collective agency of the people.

The overall design intentions are summarised with a quote by James E. Young in regard to sustainable memorial design on an urban scale:

“Its aim is not to console but to provoke; not to remain fixed but to change; not to be everlasting but to disappear; not to be ignored by passers-by but to demand interaction; not to remain pristine but to invite in its own violation and de-sanctification; not to accept graciously the burden of memory but to throw it back at the people’s feet” (Young, (1999)

References

Antonova, N., Grunt, E. & Merenkov, A. (2017) Monuments in the structure of an urban environment: the source of social memory and the marker of the urban space. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 245, 062029. DOI: 10.1088/1757-899X/245/6/062029.

Dee, C. (2004) ‘The imaginary texture of the real…’ Critical visual studies in landscape architecture: contexts, foundations and approaches. Landscape Research, 29(1), pp.13–30. DOI: 10.1080/0142639032000172424. Accessed 12 April 2022.

Elyasi, S. & Yamaçlı, R. (2023) Architectural sustainability with cultural heritage values. Available at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/cuhes (Accessed: 20 October 2025).

Gamedze, T. (2015) ‘Heritage for sale: Bronze casting and the colonial imagination’, ArtThrob, 20 November. Available at: https://artthrob.co.za/2015/11/20/heritage-for-sale-bronze-casting-and-the-colonial-imagination/ (Accessed: 21 October 2025).

Judin, H. (2021) ‘Introduction’. In: Falling Monuments: Reluctant Ruins. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Marschall, S. (2017a) ‘Monuments and affordance’. Cahiers d’Études Africaines, 57, pp.671–690.

Marschall, S. (2017b) ‘Targeting statues: Monument “vandalism” as an expression of sociopolitical protest in South Africa’. African Studies Review, 60(3), pp.203–219. DOI: 10.1017/asr.2017.85.

Marschall, S. (2003) ‘Setting up a dialogue: Monuments as a means of “writing back”’. Historia, 48(1).

Maylam, P. (1980) Rhodes, the Tswana and the British: Colonialism, collaboration and conflict in the Bechuanaland Protectorate 1885–1899. United States: Greenwood Press.

Nettleton, A. (2019) ‘By design, survival and recognition’. In: Nettleton, A. & Fubah, A.M. (eds.) Exchanging symbols: monuments and memorials in post-apartheid South Africa. Stellenbosch: African Sun Media.

Young, J.E. (1999) ‘Memory and counter-memory’. In: Constructions of memory: on monuments old and new. Harvard University.

Credits

Dr. Finzi Saidi (Lead Supervisor),

NomalangaMahlangu (Co- Supervisor)

Bonolo Masango (Co-Supervisor)

All from the Graduate School of Architecture (GSA), University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa