Editorial

A Moment in African Landscape Architecture

Leading up to the recent ILASA / IFLA Africa 2025 conference in Pretoria, the scientific committee had a few hunches about emerging themes within African landscape architecture: the shared conditions of increasing populations, urbanisation, climate crisis, and informality; the celebration of Africa's rich natural, cultural, historical, economic and linguistic diversity; the significance of Indigenous knowledges and practices; and the ongoing challenge of interrogating western traditions. The papers in this issue mirror these themes.

Common goals connect the diverse submissions: environmental stewardship through nature-based solutions and biodiversity protection; community-centred design; equity and spatial justice; thoughtful public space design; responsible heritage conservation; and the transformation of landscape architecture education.

Having attended the conference, certain narratives resonated beyond individual presentations. While the eleven papers in this issue do not represent every idea discussed at the conference or emerging across the continent, they do reveal significant dialogues currently shaping African landscape architecture.

Heritage as Living Practice

These papers challenge the idea that heritage is something relegated to the past. Akibo & Laotan-Brown demonstrate this most explicitly through their unpacking of the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove in Nigeria. Far from being a preserved UNESCO World Heritage Site, the grove is continuously activated through shared oral and ritual practices. They explain that in Yoruba cosmology, space is not functional territory or abstract geometry but "a lived and spiritual entity." As a counter to Eurocentric models of heritage conservation, they describe how the site is protected by community custodianship and spiritual taboos - an "intangible governance" (drawing on Nara, 2019). This living heritage is now under threat from urbanisation and colonial planning models that classify sacred groves as merely "undeveloped land."

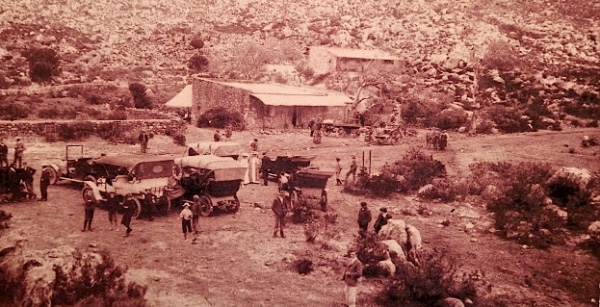

Jansen & Franklin's cultural landscape study of Eerste Tol in the Bains Kloof Pass, South Africa, reveals material evidence of a living cultural landscape. Located within a World Heritage Site, the Eerste Tol cultural landscape is understood not as individual elements but as an integrated whole, constantly evolving yet retaining its essential character. Their Landscape Character Assessment captures not just tangible features but also the production of space, sense of place and emotional connections. They show how memory, meaning and place intersect in landscapes that maintain contemporary use.

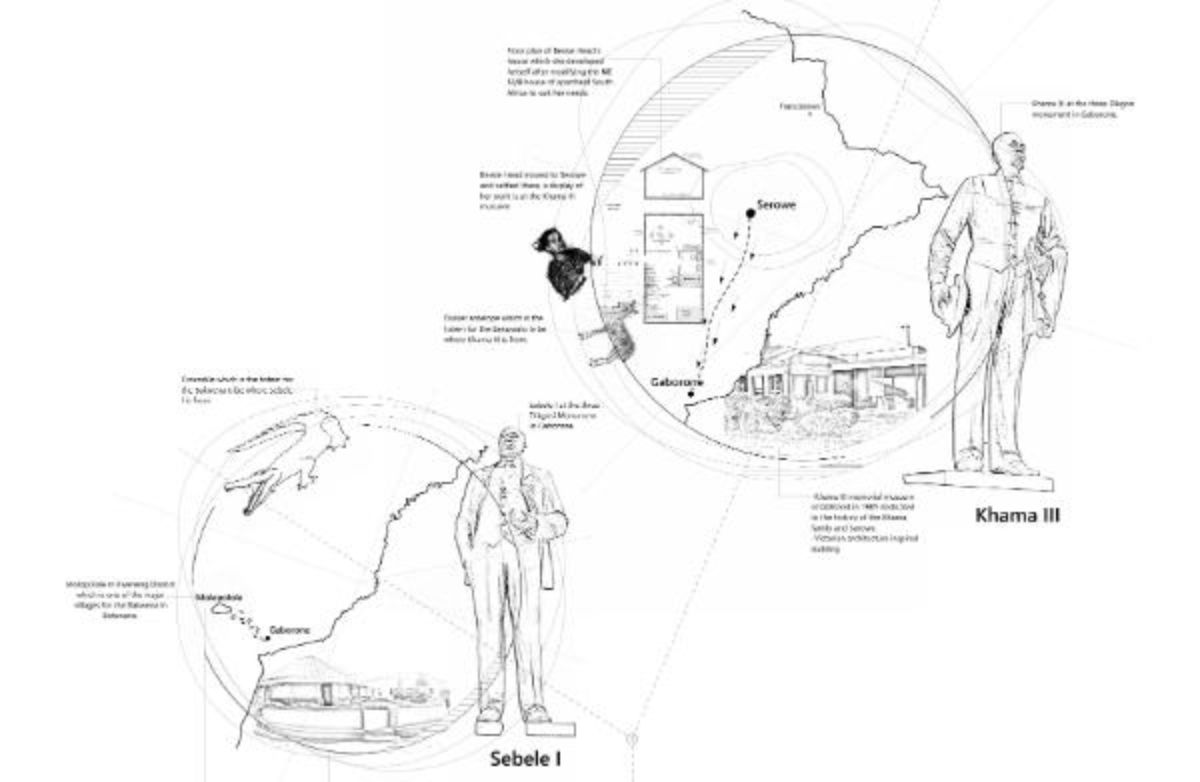

Ntale takes this concept of living heritage into provocative territory with her proposal for the Three Dikgosi Monument in Gaborone, Botswana. Rather than preserving bronze statues as static memorials, she proposes an ongoing ritual of remembrance in which communities would gradually bury the statues beneath accumulated earth during annual Independence Day celebrations. Her framing of the anti-monument challenges the static nature of memorialisation through processes of "controlled vandalism" that enable active, continuous engagement with memory-making.

Hybrid Knowledge Systems: Recognising and Elevating Indigenous Knowledge alongside Western Approaches

The conversation around living heritage prompts more profound questions about which knowledge systems are valued in landscape architecture. Several papers argue for recognising vernacular and Indigenous knowledge as equally legitimate alongside contemporary and western approaches—not replacing one with the other but creating hybrid frameworks that draw on multiple knowledge traditions.

Ntale’s paper is a reaction to the colonial aesthetic and typology of bronze statues. Her proposed reorientation and rescaling of the statues symbolise the hybridisation of Western and local African landscape practices.

Akibo & Laotan-Brown also argue for hybrid models and introduce the Heritage-Sensitive Urban Development Initiative. They propose co-designing appropriate zoning laws that recognise living cultural landscapes alongside the use of technology such as GIS audits to track changes in the landscape.

Akpami & Olanusi centralise this argument in their paper: that vernacular knowledge should be recognised as equally legitimate with scientific sustainability frameworks like sponge cities, nature-based solutions, and green infrastructure. They deliberately turn the stigma attached to informal settlements on its head, proposing we learn from them. Their argument is illustrated by three case studies: Makoko's stilt houses that address flooding and urban marginalisation; the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove, where sacredness translates into contemporary ideas of ecological stewardship and heritage conservation; and local building practices in Zaria's Savannah landscape that optimise thermal comfort and water and vegetation management practices. The authors recognise vernacular practices as sophisticated climate-responsive designs and call for this knowledge to be integrated in landscape architectural education, practice, and governance through participatory processes.

Chatoui's examination of Moroccan landscapes critiques contemporary projects such as Casablanca's modular honeycomb housing, which failed to consider Moroccan living patterns and climatic conditions, leading residents to modify their own homes. She provides a second example of Rabat's Bouregreg Valley waterfront, which, while developing commercial areas, also marginalised traditional riverbank uses by fishing and farming communities. Chatoui therefore advocates for community-centred approaches that integrate local and contemporary knowledge, designing "alongside locals" rather than for them. This is not consultation but genuine co-creation, valuing civic knowledge as essential to responsive design.

Shand's multi-year project, developing a visual lexicon of South African landscapes, makes a similar contribution. Recognising the need for better knowledge sharing and more locally relevant design informants, her paper carefully navigates the desire for "Afrocentric" design while avoiding the homogenisation of African cultures, identities, and geographies. The project aims to capture South African landscape stories, typologies, and vernacular spatial practices, building an accessible resource that supports designers in developing more representative and meaningful work.

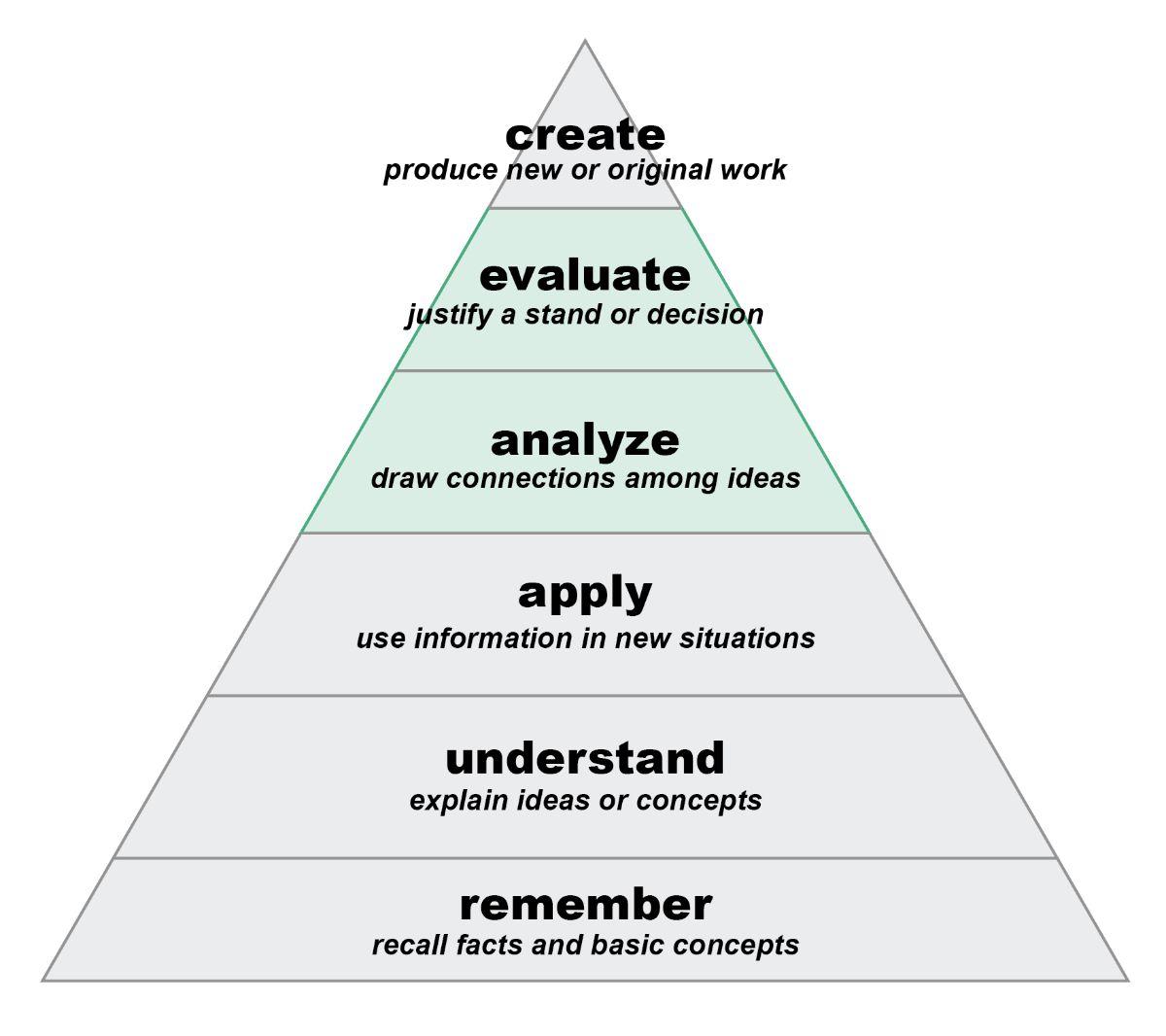

Gohar's reflective piece on landscape architecture pedagogy traces the shift from traditional teacher-centred learning to knowledge that is experiential and critically reflective. Drawing on learning theory, he describes teaching practices where instructors and students learn collaboratively from each other's experiences, acknowledging that learning looks different for each student. His classroom strategies, which include intentionally diverse groupings, flipped classrooms, multimodal engagements including field visits and multimedia resources, aim to recognise multiple ways of learning and knowing.

Practice in Action: Demonstrating Hybrid Approaches

While previous papers articulate what needs to change, the following papers demonstrate how hybrid knowledge systems can work in practice. Through built projects, experimental research, and concrete spatial interventions, these authors move from theory to implementation—demonstrating participatory processes, indigenous design principles, and community-led solutions in action.

Adeya & Kimiri's account of Kounkuey Design Initiative's work in Kibera, Nairobi, demonstrates what co-design looks like in practice. Their participatory approach to public space design in informal settlements and refugee camps is fundamentally different from conventional client relationships. It requires flexibility, acknowledging difference, and iteration—moving beyond consultation into co-creation where residents and designers work together from site selection through to material choices. Their completed public spaces demonstrate landscape architecture's transformative potential when practised as a tool for social justice, ecological restoration, and community empowerment.

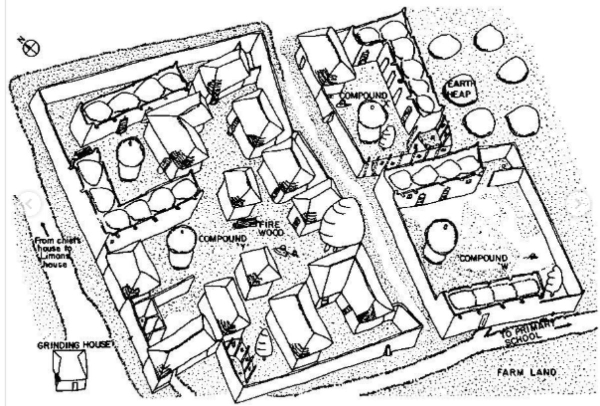

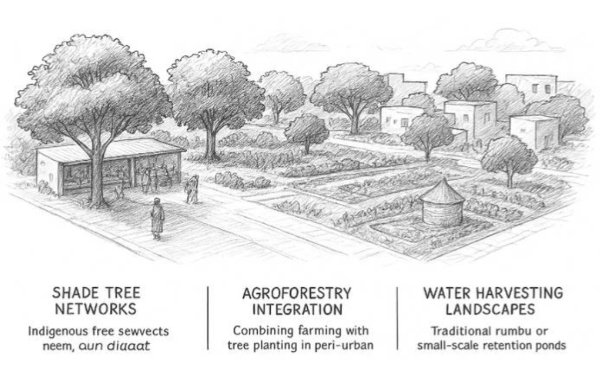

Gidado's paper echoes the call for the hybridisation of Indigenous and imported spatial practices. He argues that colonial design models have not adequately responded to cultural contexts and local climatic conditions that are being exacerbated by desertification and erratic rainfall. As examples of the rich Indigenous design knowledge that exists in Katsina State, Nigeria, he documents the Kofar Gida courtyard housing typology in Kano, market squares in Zaria that function as religious gathering spaces and respond to environmental conditions, and agroforestry practices in Fadam Gardens. Gidado graphically demonstrates how new contemporary spatial interventions can be rooted in Indigenous practices and advocates for integrating these indigenous spatial frameworks into contemporary planning, education, and policymaking.

De Beer et. al.'s experimental study contributes to this conversation through their focus on Traditional African Vegetables (TAVs) rather than conventional crops. Their research demonstrates that nutrient-rich, culturally relevant crops like Coleus and Portulacaria not only produce higher biomass yields than conventional vegetables but are also more resilient to climate stress. By centring African food cultures within innovative living wall systems, they challenge assumptions about what constitutes "modern" or "advanced" agricultural technology.

Expanding Ways of Knowing, Transitioning Roles

Running through these three themes of living heritage, hybrid knowledge recognition, and practice in action are two interconnected conversations about the future of landscape architecture in Africa.

The first concerns how we know and communicate knowledge. Several papers implicitly argue for epistemological diversity and humility. Gidado describes "local ontologies" embedded in spatial arrangements. Akibo & Laotan-Brown discuss "intangible governance" and ritual understandings. There may be knowledge that remains with communities, inaccessible or inappropriate for outsider documentation. This recognition of the unknowable represents an ethical stance: not all knowledge should be extracted and circulated. Shand's visual lexicon project embodies this diversity practically, centring images, typologies, and stories that communicate spatial and experiential understanding more effectively than text alone, acknowledging that landscape knowledge is often visual, embodied, and narrative.

The second conversation concerns professional roles and authority: who gets to design African landscapes? Whose knowledge counts? The papers recognise those who are already shaping Africa’s landscapes: Akpami & Olanusi show residents of Makoko and Zaria have long been designing sophisticated climate-responsive solutions; Chatoui demonstrates Moroccan communities modifying imported housing to their cultural practices; Ntale proposes communities actively making and remaking memorial landscapes through ongoing ritual. Adeya & Kimiri's participatory practice positions landscape architects not as sole authors but as facilitators collaborating with communities from site selection through material choices. Together, these papers suggest the profession's role is transitioning from the expert imposing solutions to collaborator learning from and designing with communities.

These eleven papers do not represent a comprehensive picture, but a snippet of some of the conversations shaping African landscape architecture. They demonstrate work that is simultaneously theoretical and grounded, critical, and constructive, rooted in specific places yet part of continental dialogues. The conversations traced here will undoubtedly continue, evolve, and be joined by others as the discipline continues to reframe what African landscapes are, how we understand them, and who gets to shape them.