Commentary: Theory and Practice in Teaching Landscape Architecture

Les enseignants en architecture de paysage continuent souvent d'enseigner et de présenter des idées innovantes avec peu d'opportunités de réflexion critique, notamment concernant le décalage entre les cadres pédagogiques et les réalités de la pratique dans l'enseignement supérieur du paysage. S'appuyant sur plus de deux décennies d'expérience, notamment dans le développement de nouveaux programmes, la gestion réussie de cursus établis et la transformation de cursus peu performants, cet article de réflexion explore comment l'enseignement des théories en architecture de paysage peut mieux aligner les pratiques pédagogiques sur l'engagement des étudiants face aux complexités spatiales, écologiques et culturelles. Cette réflexion souligne l'importance d'encourager les étudiants à évaluer de manière critique leurs décisions de conception dans des contextes sociaux, environnementaux et éthiques plus larges. Elle souligne également comment la reconnaissance de la diversité des styles d'apprentissage et des origines culturelles contribue à un environnement d'apprentissage plus inclusif et plus réactif. Le respect des perspectives individuelles favorise une culture d'atelier collaborative, où des expériences variées enrichissent à la fois le processus de conception et ses résultats. Enfin, l'article examine comment l'intégration des outils numériques dans l'enseignement de l'architecture de paysage peut améliorer significativement les capacités des étudiants en visualisation, analyse et communication. Ces compétences sont de plus en plus essentielles dans la pratique du design contemporain.

Landscape architecture educators often continue teaching and introducing innovative ideas with limited opportunities for critical reflection, particularly regarding the disconnect between pedagogical frameworks and the realities of practice in landscape higher education. Drawing on over two decades of experience, including the development of new programs, the successful management of established curricula, and the transformation of underperforming ones, this reflective piece explores how teaching theories in landscape architecture can better align educational practices with students’ engagement in spatial, ecological, and cultural complexities. The reflection emphasises the importance of encouraging students to critically evaluate their design decisions within broader social, environmental, and ethical contexts. It also highlights how acknowledging diverse learning styles and cultural backgrounds contributes to a more inclusive and responsive learning environment. Respecting individual perspectives fosters a collaborative studio culture, where varied experiences enrich both the design process and its outcomes. Finally, the piece considers how the integration of digital tools in landscape architecture education can significantly enhance students’ abilities in visualisation, analysis, and communication. These skills are increasingly essential in contemporary design practice.

Introduction

Reflective pedagogy is an instructional approach in which educators consistently evaluate and refine their teaching and learning.

It started with the inception of modern academia and has evolved to date. Tutors possess a deep understanding of student learning processes and are willing to reflect on and adapt their pedagogical practices continuously.

The contemporary teaching frameworks extend beyond the mere transmission of knowledge, moving away from a traditional, teacher-centred model to one that is more experiential and reflective. This approach emphasises the importance of the "tutor-student" relationship, encouraging both parties to engage in critical reflection and mutual learning, as argued by (Freire et al., 2005). In this essay, I draw upon my dual roles as an academic and a professional practitioner, informed by my experience teaching landscape architecture at different departments and universities.

Teaching Theories

Learning landscape architecture depends heavily on an iterative process, with critical reflection at its core.

This approach necessitates that students consistently reflect on their work, both individually and in group work. The importance of reflection in the learning process is emphasised across all disciplines and backed up by many theories. Dewey (1933), an early educational theorist, described reflective thinking as an active and intentional cognitive process that enables students to think critically and question everything. Boud et al (1985) equally underscores the significance of reflection and evaluation in the learning process, promoting individuality and accountability.

Kolb and Kolb (2013) developed a learning cycle that consists of four stages: (i) concrete experience, where learners encounter a new situation or re-evaluate an existing one; (ii) reflective observation follows, during which learners consider their experiences from different perspectives, integrating their feelings and thoughts; (iii) abstract conceptualisation, involves forming new ideas or revising existing ones; and (iv) active experimentation, where learners apply their new insights in different situations, starting the cycle anew. I have been using such a model in teaching design studios and graduate seminars both in the USA and the UK, without being fully aware of Kolb’s model.

The similarity between the conceptual framework of Kolb’s model and that of landscape planning and design is unmistakable. Both frameworks emphasise reflection and embody an inherent learning process.

Schön (1987) argues that the challenges in the landscape architecture studios require both action and reflection-in-action, mirroring professional practice. He outlined three stages: (i) knowledge-in-action, where students draw on their prior experiences; (ii) reflection-in-action, which occurs during the problem-solving process, and finally, (iii) reflection-on-action, where students evaluate their work and refine their solutions. In schools of landscape design and planning, I encountered environments that either facilitate or restrict such models. While design schools adopt a more hands-on project-based experiential approach, some landscape architecture schools lean towards a more conventional setting where students engage in research, presentations, and in-class discussions, primarily through verbal communication.

Schön (1987) emphasizes the critical role of the educator in helping students evaluate their practice. This is aligned with other reflective models that emphasise the role of reflection in learning and development. The work of Boud et al. (1985) introduced a model with three stages: (i) experience, (ii) reflective process, and (iii) outcomes. Graham Gibbs (1988) developed a more structured cyclical model of reflection, which includes stages such as description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusion, and action plan. Rolfe et al. (2001) also proposed a structured framework for reflective practice, guided by the questions "What?" (description), "So what?" (analysis), and "Now what?" (action).

While these models share common themes, they also differ in their approaches to reflective learning. Boud et al. (1985) and Rolfe et al. (2001) offer more general frameworks, with Boud placing greater emphasis on the emotional aspects of reflection, while Rolfe focuses on practical application through his guiding questions. These approaches differ from the Gibbs and Unit (1988) model, which provides a detailed breakdown of the reflection process, including specific steps for evaluation and analysis. Although Gibbs' model can be seen as somewhat prescriptive, it offers a systematic approach to practising reflection through experiential learning, aligning closely with Kolb's theory but with additional structured steps.

Reflective Thinking in Landscape Design and Planning

My primary goal in student learning is to emphasise the importance of reflection, encouraging students to go beyond merely meeting requirements. I want them to question assumptions, challenge their understanding, and redefine their perspectives. Landscape architects must engage with the social and cultural dimensions of their work. Through my teaching, I aim to prepare students to tackle complex global issues such as climate change, racial justice, and civic engagement, empowering them to become advocates for meaningful change.

In line with Schön's theories, my classroom environment functions as an open and inclusive forum for dialogue. I work collaboratively with students, sharing and learning from each other's experiences. This approach encourages students to express their interpretations and engage in discussions. I often find myself learning from my students, who bring new insights, refuting the idea that students are passive recipients of knowledge.

Kolb (2013) discusses that the learning cycle is iterative, where each time the cycle is completed, the experience is different. At the end of each semester, I find it crucial to reflect on my teaching practices and encourage students to reflect on their work. This approach fosters self-directed learning, where students become active participants in their education. I consider student evaluations and feedback as essential tools for gaining insight into their perspectives and promoting a healthy reciprocal learning environment. Accordingly, my focus remains on optimising student involvement and participation in class. As an educator, I aim to create a platform for sharing knowledge and experiences through various methods, including lectures, seminars, discussions, studio work, guest lectures, field visits, blogs, and surveys. These formats engage students and help them develop key skills like event management and teamwork.

I strive to bring my landscape planning experiences into higher education by integrating real-world insights and practical skills into my programmes and classes.

This approach enhances reflection and bridges the gap between theory and practice, ensuring students are prepared for their careers. This has been aligned with the findings of Hasanefendic et al. (2017) who highlight the added value of innovative approaches to teaching, including bringing professional experience to the classroom.

Respect Individual and Diversity Learning

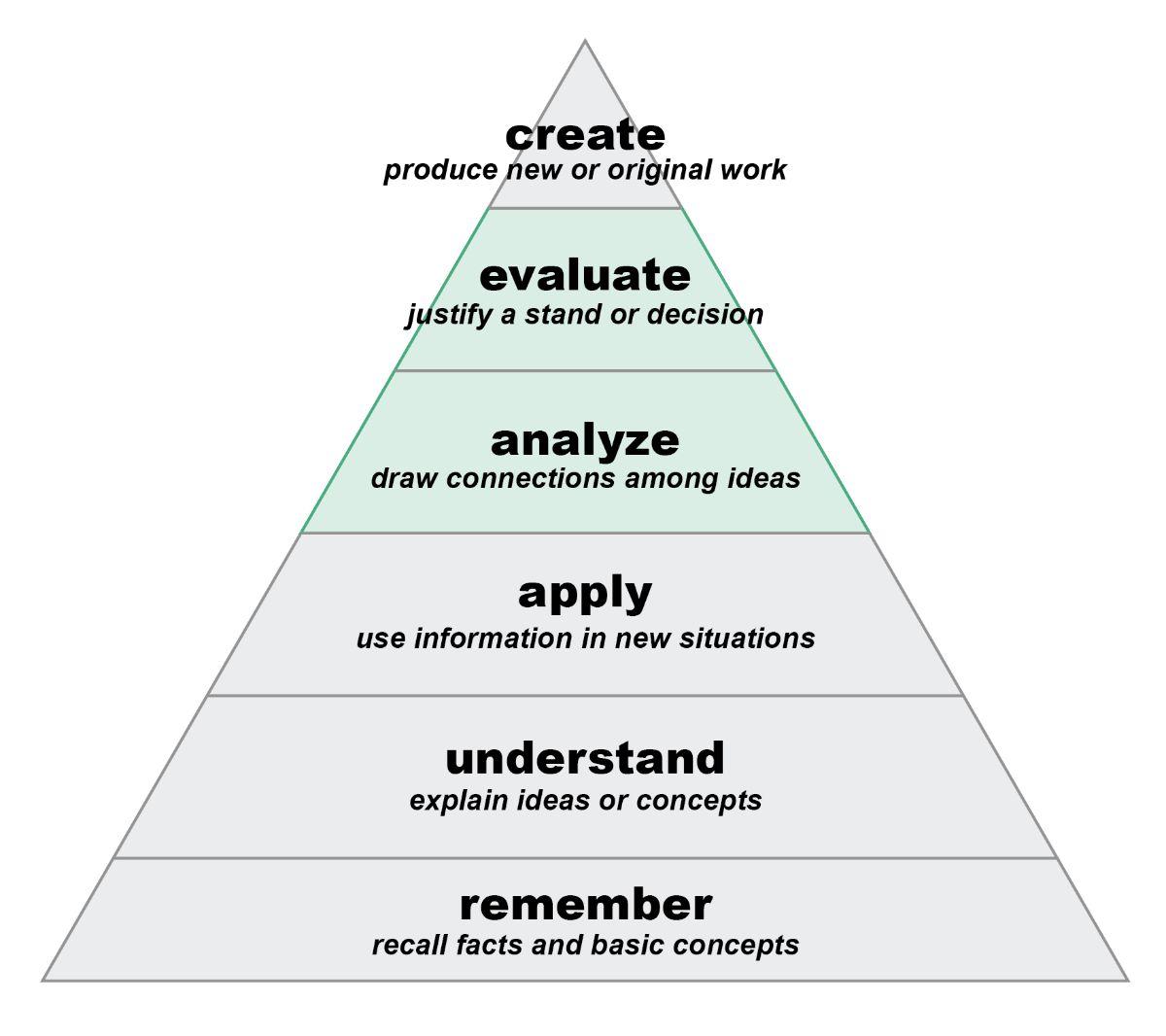

Kolb and Kolb (2013) suggest that individuals have distinct learning styles, which are diverging, assimilating, converging, and accommodating, that align with the stages of the experiential learning cycle. In addition, long-established models like Benjamin Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956) and Howard Gardner’s (Gardner, 2011) theory of multiple intelligences demonstrate the students’ multiple levels of understanding and diverse learning needs. This implies that educators should employ multimodal teaching approaches that cater to diverse learning styles, thereby promoting inclusive, experiential, and reflective learning experiences. Like the previous figures, Fig.3 shows Bloom's revised taxonomy with the reflective components highlighted in green (Anderson et al., 2001).

Through this collaborative and inclusive learning process, I have consistently contributed to an environment that promotes diversity and collegiality among students, particularly in group work settings. I make sure students’ groups incorporate diverse ethnicities, genders nationalities, and backgrounds to encourage a healthy learning environment. I also ensure there is diversity in the skill set students have, so every group has an equal and varied combination of skills. Especially in landscape architecture, this involves applying Rose’s (2000) principles of the Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which consist of three principles for curriculum development that provide diverse individuals with equal opportunities to learn. These principles include providing multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement to facilitate access to all learners. Integrating these theories, I involve varying modes of representation and formats in the curriculum including text, audio, visual representations, digital textbooks, and interactive simulations. I also encourage students to demonstrate their understanding through various forms, such as essays, presentations, and projects. Additionally, I emphasise student autonomy to encourage them to be engaged and actively participate in the course activities to improve their learning process.

As educators, we must respect the students’ backgrounds, allowing the interchange of ideas to produce new knowledge, so that teaching a subject like landscape architecture is not driven in one direction but remains open to offer a chance for individualisation and personalised understanding.

Everything that a student brings into the class has a meaning and is mainly influenced by their environment, which is situated outside the classroom. Thus, it is essential to accommodate and respect such influences and ideas, providing a safe and inclusive environment for the students to reveal their value systems. This is aligned with Webster (2004) who argues that this paradigm views teaching as a collaborative process that supports students' development and transforms their understanding.

Following on (UK Public General Acts, 2010), (Wolbring and Lillywhite, 2021) and (Watts, 2022) achieving the highest levels of Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) in higher education necessitates consideration of various characteristics, including race, class, ethnicity, and gender. Reflecting on my own teaching experience, I have identified race, class, ethnicity, and gender as prominent factors impacting student experiences in universities. To address these disparities and promote EDI, I have implemented several strategies:

(i) Gender & Ethnicity: Recognising cultural preferences, such as Middle Eastern students preferring to stay in same-gender groups and Chinese students gravitating towards familiar language groups, I ensure diverse groupings for collaborative work to foster a healthier class environment and enhance knowledge sharing.

(ii) Class: Addressing disparities in socio-economic status, particularly evident in technology access discrepancies, I diversify group assignments to mitigate challenges arising from unequal resources. By offering students choices and guidance, I promote inclusivity and equitable opportunities for participation.

(iii) Computer Literacy: Acknowledging varying levels of proficiency in technology among students from diverse academic backgrounds, I structure group assignments to distribute skills evenly and ensure equitable learning opportunities. For individual tasks, I facilitate access to necessary support services and implement cost-effective solutions, such as digital presentations instead of printing materials, to accommodate all students' needs.

Using Digital Technologies

With the rise of technology in landscape architecture, there has been an expansion in activities that professors can use to cater to diverse learning preferences and engage students. Multimedia theory suggests that people process new information more effectively when it is presented through multiple modes (Mayer, 1997), which aligns well with UDL’s principles. I employ various strategies to incorporate technology into my teaching approach. This includes using digital learning platforms such as online learning management systems and virtual classrooms to deliver course content and manage assignments digitally.

These tools support the flipped classroom model, which enhances students’ self-directed learning and provides opportunities for engagement with content outside of class, freeing up class time for discussion and interactive activities.

Additionally, technology enables a blended learning format where online components complement personal instruction, offering greater flexibility and learning opportunities for distant and part-time students. I also ensure to incorporate multimedia elements such as videos, simulations, and visualisations that simplify complex ideas into more engaging content for students. These strategies aim to create an inclusive learning environment that supports diverse student populations and promotes academic success irrespective of individual characteristics or circumstances.

Conclusion

As landscape educators, we must use teaching theories to understand what students want and how they learn, making learning more adaptable and responsive.

In a changing world, we should teach students to evolve rather than follow fixed truths, as our discipline is deeply tied to shifting societies, environments, and cultural narratives. I see the classroom as a shared space where both professors and students learn from each other, and where reflection on this exchange becomes a tool for growth and transformation.

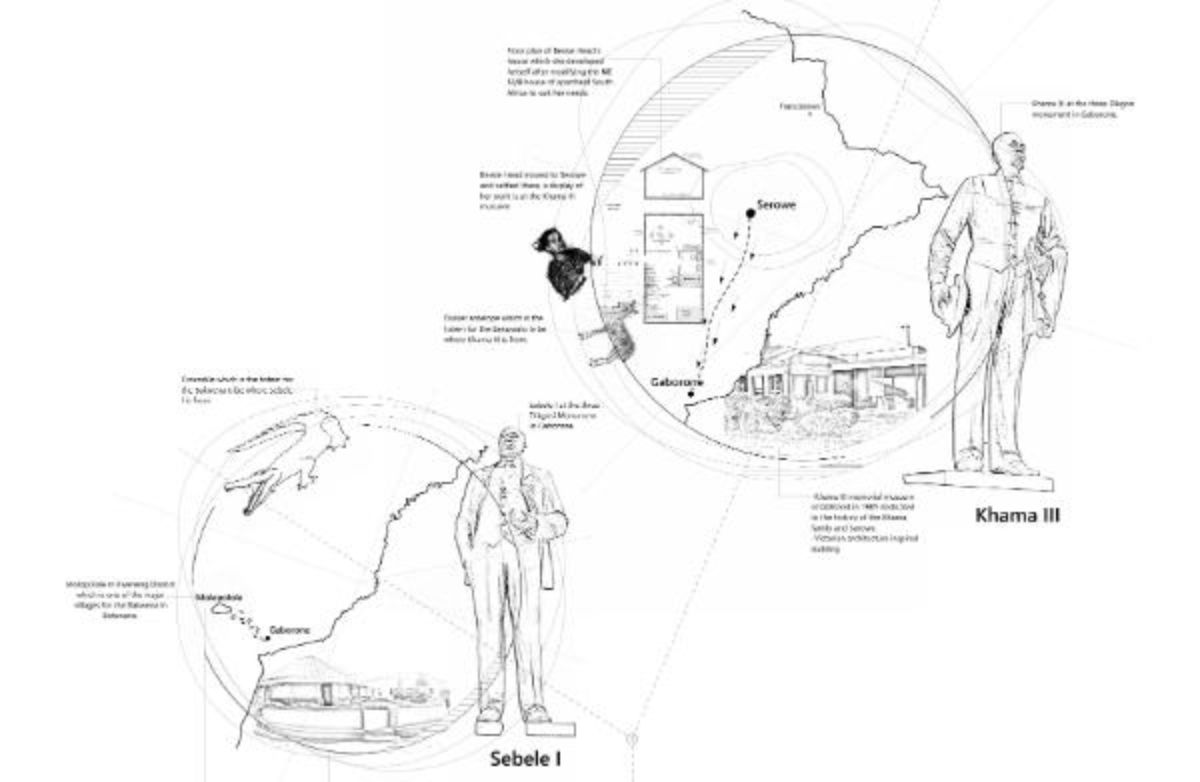

Landscape education varies across cultures and institutional frameworks, as the discipline itself is not uniformly defined or practised. Its relevance and applicability become broader and more meaningful only when teaching approaches are adapted to specific cultural contexts, acknowledging local values, knowledge systems, and ways of relating to the landscape.

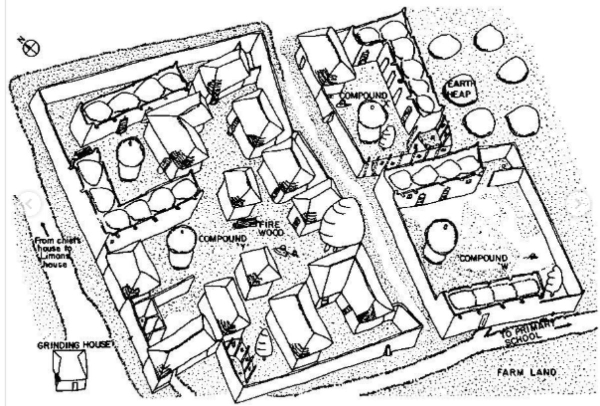

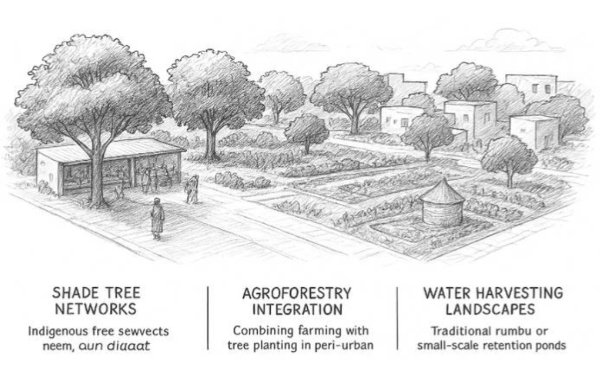

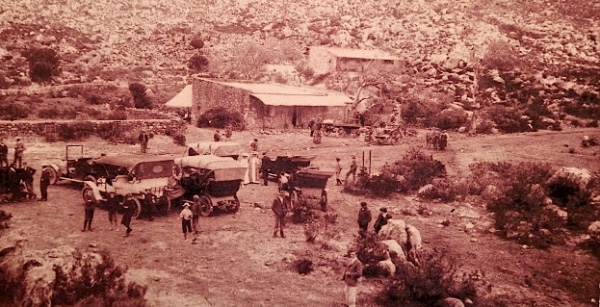

Leading and teaching landscape programmes in several universities, it is crucial to understand that teaching across different cultural contexts calls for sensitivity to how landscape is perceived, valued, and lived. Educational approaches that work in one region may not translate directly elsewhere; thus, we must engage with local knowledge systems, social dynamics, and environmental realities. In this sense, the classroom becomes a place to bridge global theories with local practices, where indigenous and contemporary understandings of landscape can coexist and inform one another. This requires moving beyond conventional education, blending theory with practice, and empowering students to become reflective and contextually aware urbanists and designers who can respond critically to the places they inhabit and shape.

References

Anderson, L. et al. (2001) A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

Bloom, B. (1956) Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Longman Group.

Boud, D., Keogh, R. and Walker, D. (1985) Reflection: Turning Reflection into Learning. Routledge.

Dewey, J. (1933) How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process. Boston: D.C. Heath & Co Publishers.

Freire, Paulo. et al. (2005) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Gardner, H. (2011) Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Basic Books.

Gibbs, G. and Unit, G.Britain.F.E. (1988) Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. FEU Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=z2CxAAAACAAJ.

Hasanefendic, S. et al. (2017) ‘Individuals in Action: Bringing about Innovation in Higher Education’. European Journal of Higher Education, 7(2), pp. 101–119. DOI: 10.1080/21568235.2017.1296367.

Kolb, A. and Kolb, D. (2013) The Kolb Learning Style Inventory: A Comprehensive Guide to the Theory, Psychometrics, Research on Validity and Educational Applications. Experience Based Learning Systems, Inc. Available at: www.learningfromexperience.com.

Mayer, R.E. (1997) ‘Multimedia Learning: Are We Asking the Right Questions?’ Educational Psychologist, 32(1), pp. 1–19. DOI: 10.1207/s15326985ep3201_1.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D. and Jasper, M. (2001) Critical Reflection for Nursing and the Helping Professions: A User’s Guide. Palgrave MacMillan.

Rose, D. (2000) ‘Universal Design for Learning Associate Editor’s Column’. Journal of Special Education Technology.

Schön, D. (1987) Educating the Reflective Practitioner. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

UK Public General Acts. (2010) Equality Act 2010. London.

Watts, C. (2022) How to Promote Equality, Diversity & Inclusion in the Classroom. Available at: https://www.highspeedtraining.co.uk/hub/classroom-equality-diversity/ (Accessed: 13 February 2024).

Webster, H. (2004) ‘Facilitating Critically Reflective Learning: Excavating the Role of the Design Tutor in Architectural Education’. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 2(3), pp. 101–111. DOI: 10.1386/adch.2.3.101/0.

Wolbring, G. and Lillywhite, A. (2021) ‘Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) in Universities: The Case of Disabled People’. Societies, 11(2). DOI: 10.3390/SOC11020049.

Credits

I extend my sincere gratitude to my dear friend and colleague, Hadwa Ahmed, for her invaluable assistance with this paper. Our discussions and reflections on various practices greatly enriched this work.