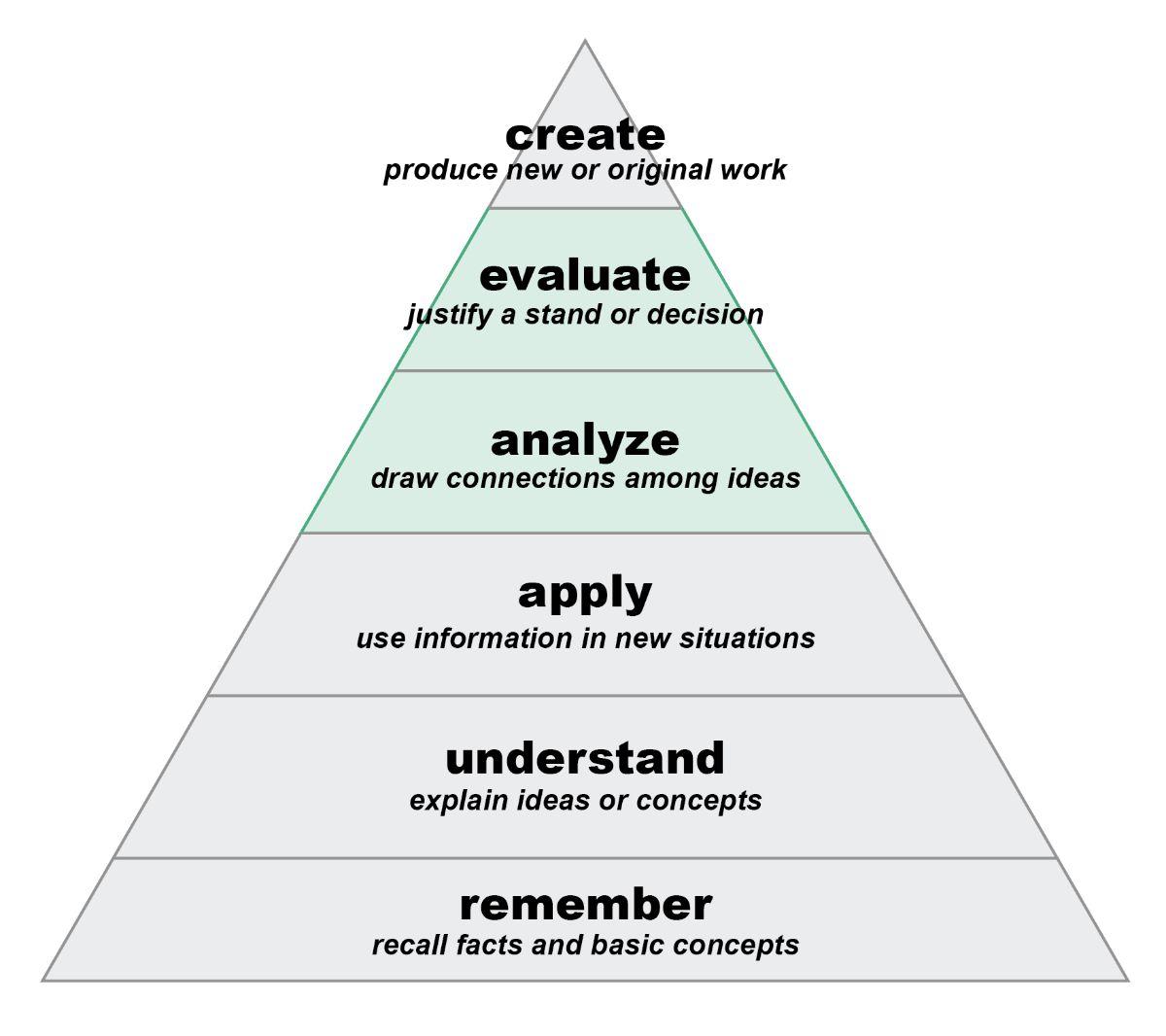

Harnessing Indigenous Spatial Practices for Contemporary Landscape Design in Katsina State, Nigeria

L'État de Katsina, dans le nord du Nigeria, riche de ses pratiques spatiales indigènes, est confronté à des défis environnementaux tels que la désertification, le stress thermique et la fragmentation sociale dus à l'urbanisation rapide, à l'aménagement urbain de l'époque coloniale et aux paradigmes modernistes en matière de conception. L'étude explore l'utilisation de logiques spatiales indigènes, telles que les maisons avec cour intérieure, les marchés ombragés et les bosquets sacrés, dans la conception paysagère contemporaine et la résilience climatique dans l'État de Katsina. À l'aide d'une approche qualitative par étude de cas, des données ont été recueillies à travers des observations sur le terrain, des croquis, des entretiens et une documentation photographique des complexes traditionnels et des espaces communautaires. L'analyse thématique a révélé quatre domaines interdépendants : l'identité culturelle, l'adaptation écologique, la perturbation coloniale et l'innovation en matière de conception. Les résultats indiquent que les typologies indigènes de cours intérieures améliorent le refroidissement passif et l'intimité, que les bosquets sacrés fonctionnent comme des ancrages environnementaux et spirituels, et que les espaces gérés par la communauté maintiennent l'équilibre socio-environnemental. L'étude propose un cadre paysager résilient intégrant les systèmes de logement vernaculaires, les infrastructures vertes et la co-conception communautaire afin de promouvoir la durabilité et la continuité du patrimoine. Elle soutient que l'intégration de la sagesse indigène dans l'enseignement de la planification et de la conception peut décoloniser la pratique spatiale tout en répondant aux défis climatiques et culturels dans le Nigeria semi-aride. La recherche conclut que la revitalisation des pratiques spatiales indigènes constitue une stratégie efficace, peu coûteuse et culturellement pertinente pour créer des paysages urbains résilients, inclusifs et adaptés au climat dans l'État de Katsina.

Katsina State in northern Nigeria, with its rich Indigenous spatial practices, faces environmental challenges like desertification, heat stress, and social fragmentation due to rapid urbanization, colonial-era planning, and modernist design paradigms. The study explores the use of indigenous spatial logics, such as courtyard housing, shaded markets, and sacred groves, in contemporary landscape design and climate resilience in Katsina State. Employing a qualitative case study approach, data were collected through field observations, sketches, interviews, and photographic documentation of traditional compounds and community spaces. Thematic analysis revealed four interlinked domains: cultural identity, ecological adaptation, colonial disruption, and design innovation. Findings indicate that indigenous courtyard typologies enhance passive cooling and privacy; sacred groves function as environmental and spiritual anchors; and community-managed spaces sustain socio-environmental balance. The study proposes a resilient landscape framework integrating vernacular housing systems, green infrastructure, and community-based co-design to promote sustainability and heritage continuity. It argues that integrating Indigenous wisdom into planning and design education can decolonise spatial practice while addressing climate and cultural challenges in semi-arid Nigeria. The research concludes that revitalising Indigenous spatial practices provides an effective, low-cost, and culturally resonant strategy for achieving resilient, inclusive, and climate-responsive urban landscapes in Katsina State.

Background

Katsina State in northern Nigeria, endowed with a rich cultural heritage and long-standing settlement patterns, today faces ecological challenges partly rooted in traditional land-use practices and heritage-driven spatial practices. The preservation of historic sites such as the 15th-century Gobarau Minaret and the Durbi Takusheyi burial grounds has limited adaptive land management, contributing to issues like desertification, erratic rainfall impacts, and socio-economic pressures (Lawal, 2024; Bawale et al., 2025). These practices, once effective in balancing human, spiritual, and environmental needs, are increasingly strained under developmental demands.

Courtyards, shaded communal markets, and sacred groves are enduring indigenous design forms in Nigeria, valued for their social, cultural, and climatic functions (Usman et al., 2024).

Research indicates that enclosed structures enhance passive cooling, natural ventilation, and microclimatic regulation, thereby decreasing reliance on artificial energy sources in hot climates. Complementary research indicates that courtyard geometry and the integration of vegetation significantly enhance thermal comfort in tropical environments.

Open spaces in Katsina and nearby regions promote cultural and social adaptation against climate stress, while traditional practices in Batagarawa foster resilience (Gidado et al., 2024). Indigenous practices, despite their value, are being undermined by colonial planning, rapid urbanisation, and imported design models that are often unsuitable for local climatic and cultural contexts (Bawale et al., 2025). Climate change, causing droughts and flooding, is posing significant threats to cultural heritage, environmental stability, and community cohesion (Lawal, 2024). Nigeria's emerging scholarship highlights the potential of hybrid approaches combining indigenous spatial logics with modern sustainability principles, demonstrating how these strategies can reduce energy consumption and enhance resilience (Kalu, Ogunnaike, & Eze, 2025). Case studies in Southeastern Nigeria show that integrating vernacular architecture with green roofs and efficient materials enhances climate-responsive design while maintaining cultural relevance (Kalu et al., 2025).

Integrating Indigenous spatial practices into contemporary design strategies in Katsina State is crucial for decolonising landscape architecture and offering culturally sensitive, environmentally sustainable solutions.

Literature Review

Indigenous Spatial Practices in African Contexts

Across Africa, Indigenous spatial practices have long reflected ecological adaptation, social cohesion, and cosmological order. From the Swahili stone towns of East Africa to the Hausa-Fulani courtyard houses of Northern Nigeria, space-making was guided by environmental logic and collective life (Oliver, 2020; Prussin, 1999). These settlements evolved organically, courtyards moderated heat and dust, shaded markets fostered exchange, and sacred groves provided ecological and spiritual balance.

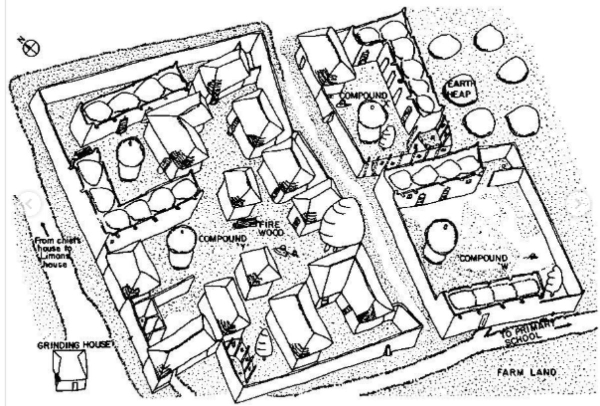

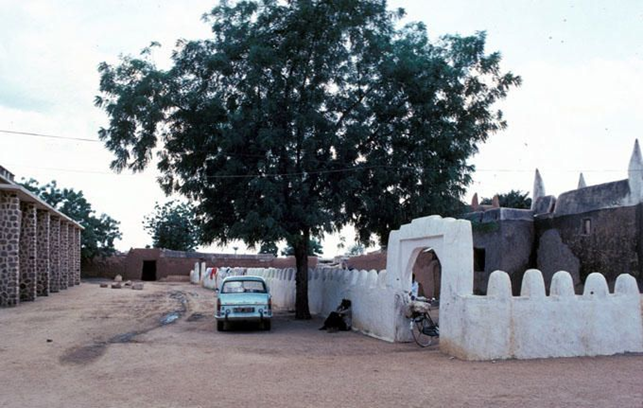

In Katsina and neighbouring Hausa cities, the zaure -to-courtyard sequence (zaure being a semi-enclosed entrance hall or reception space traditionally used for receiving visitors and providing privacy to the inner courtyard) created a spatial gradient from public to private life, symbolising both cultural order and climate adaptation (Figure 1). Such patterns reveal a spatial intelligence that modern planning has often overlooked.

Colonial Disruption of Indigenous Landscapes

Colonial interventions introduced rigid, Eurocentric urban models that contrasted sharply with the fluidity of indigenous systems. British administrators imposed grid-based planning, zoning, and segregationist residential quarters (Figure 2) that prioritised visibility and order over climatic and social logic (Mabogunje, 2019; Enwezor, 2019). In cities like Katsina, Zaria, and Kano, traditional compounds and street networks were realigned or displaced to fit imported geometric ideals.

Modernism, Eurocentric Design, and the Continuity of Colonial Ideals

Postcolonial urban planning in Northern Nigeria often perpetuated colonial ideals under the guise of modernisation. Concrete materials, detached housing, and expansive road networks became symbols of progress but ignored climatic responsiveness (Nwanna, 2021). This trend reinforced the “Eurocentric aesthetic” symmetry, visibility, and monumentality, while displacing traditional social configurations.

In contrast, contemporary design responses that reintroduce courtyard logics, shaded pathways, and indigenous planting systems directly challenge this legacy. Illustrations contrasting a colonial-style open-grid housing layout with a vernacular-inspired compact courtyard cluster would clearly demonstrate how modernist designs undermine both climatic comfort and cultural identity.

Relevance of Indigenous Practices to Contemporary Design

Recent studies reiterate that Indigenous systems offer valuable lessons for climate-responsive, community-centred design. Courtyard housing typologies, for instance, naturally regulate temperature and foster social cohesion (Gunasekaran & Shanthi Priya, 2025; Zhang et al., 2024). Integrating these with modern sustainability tools, such as passive ventilation modelling, hybrid materials and water harvesting, can restore ecological and cultural balance.

Decolonising Design and Cultural Resilience

The movement to decolonise design calls for a shift from Eurocentric paradigms toward frameworks rooted in local epistemologies (Escobar, 2018; Jokilehto, 2020).

In landscape architecture, this means re-engaging Indigenous knowledge not as nostalgia but as innovation.

In Katsina, integrating communal courtyards and sacred grove practices into urban design can generate contextually appropriate solutions for resilience.

Methodology

Research Design

This study employs a qualitative research design, utilising a case study approach. The emphasis is on exploring how Indigenous spatial practices in Katsina State can be systematically integrated into contemporary landscape design strategies. A qualitative framework is appropriate because it enables an in-depth understanding of cultural, social, and environmental dimensions embedded in traditional practices (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

Study Area

The research focuses on Katsina State, located in the semi-arid region of Northern Nigeria. The state provides a relevant context due to its combination of rich indigenous heritage, including Hausa courtyard houses, sacred groves, and pressing contemporary challenges such as desertification, rapid urbanisation, and climate-induced environmental stress (Lawal, 2024; Bawale, Muazu, & Dankullu, 2025).

Data Collection Methods

The study explored Indigenous spatial practices in Katsina State using various qualitative methods, including direct observations, sketches, photographs and field notes, to document traditional configurations, vegetation use, and landscape patterns. Semi-structured interviews with local stakeholders explored indigenous practices, colonial and modern disruptions, and adaptation opportunities in landscape design, ensuring lived experiences and local perspectives were central to the research process (Bryman, 2016). The study analyses case studies of indigenous compounds and community-managed spaces to contextualise findings and emphasise the importance of indigenous spatial practices in sustainable design strategies (Prussin, 1999; Kalu, Ogunnaike, & Eze, 2025).

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using thematic analysis. Codes were developed around four core themes: cultural identity, ecological adaptation, colonial disruptions, and contemporary design opportunities. The study is qualitative and context-specific, which may limit generalizability. However, its strength lies in generating contextually grounded insights and design propositions that can inform both practice and future research in similar semi-arid African contexts.

Case Study Findings

Case Study One: Courtyard Housing in Kano

In the modern housing landscape of Kano, the traditional Kofar Gida (house frontage) courtyard typology is being thoughtfully reinterpreted within contemporary estates (Figure 1). Architects are rediscovering the value of organising dwellings around semi-private courtyards to maintain privacy, enhance social functionality, and reap the benefits of passive cooling (Agboola & Zango, 2014). The spatial hierarchy beginning with the zaure, continues through to the courtyard. However, it is now being reinterpreted in a more compact form to suit contemporary living. Meanwhile, the revival of indigenous decorative elements alongside modern materials ensures that cultural aesthetics endure within structurally sound and climatically responsive environments. These adaptations affirm the courtyard’s role not only as an architectural device but as a vital cultural and environmental strategy for sustainable housing in Kano.

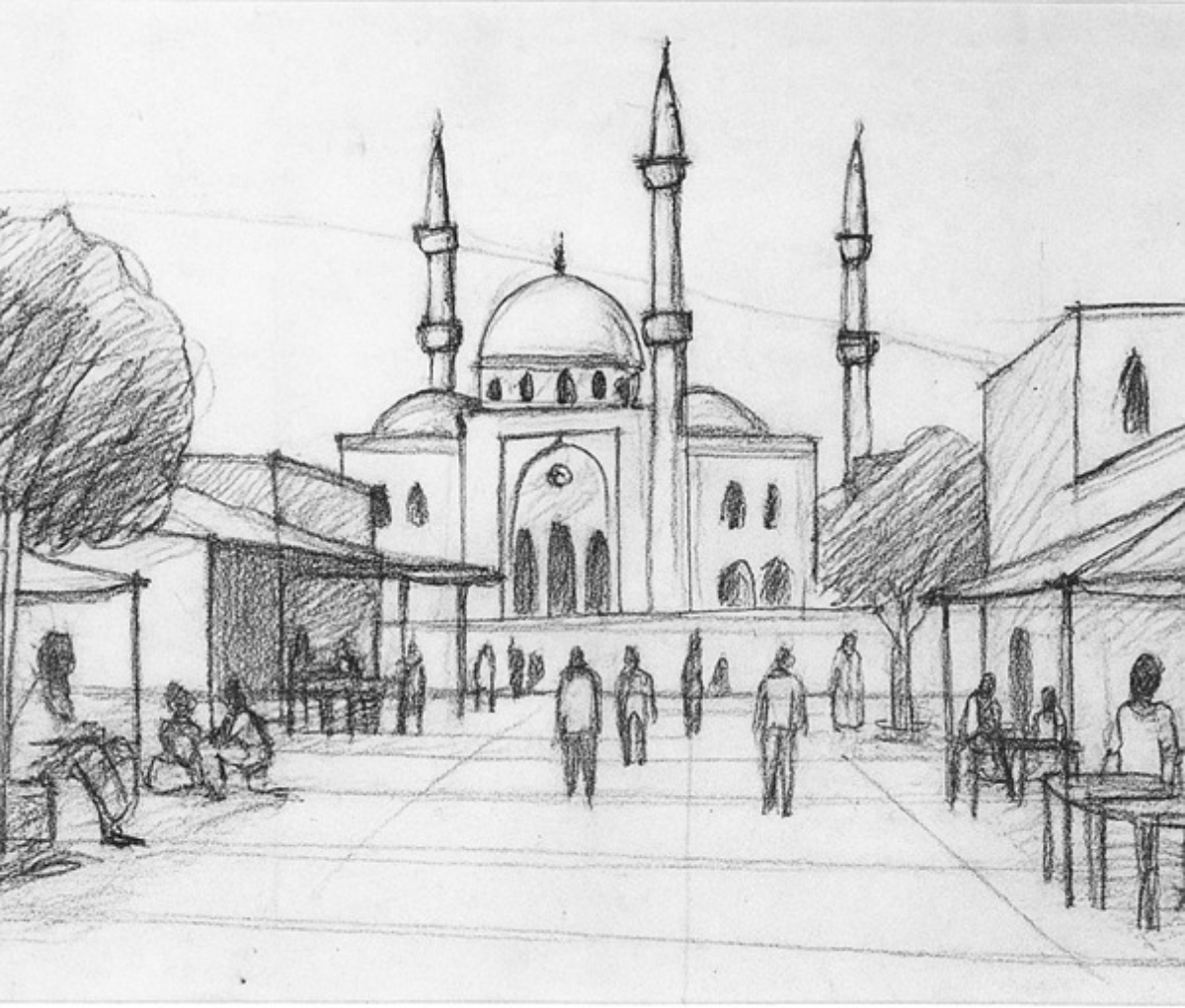

Case Study Two: Market Squares in Zaria

In Zaria, market squares are not mere marketplaces but living theatres of Hausa social and spiritual life (Figure 4). The design imperative is to retain their cultural fluidity while enhancing climate resilience. By combining shaded architectural elements, permeable surfaces, flexible spatial configurations, and symbolic markers, these plazas can function seasonally as marketplaces, religious gathering grounds, parade routes, and venues for community cohesion. Thoughtful reinvention ensures that environmental stresses, like heat, dust and desert encroachment, do not displace cultural traditions but are met with adaptive, inclusive design strategies (Gidado et al., 2023).

Lessons learned from the case studies

a) Indigenous spatial approaches prioritise seclusion , social order, and cultural continuity, utilising zaure-to-courtyard sequences, ornamental patterns, symbolic markers, and embedded traditions to create multipurpose places for social gatherings and spiritual practice, as well as

b) Emphasise the need for passive cooling and adaptive reuse in urban areas for boosting climate resilience, ecosystem services, and ecological balance.

Indigenous Spatial Practices in Katsina State

Field observations and interviews revealed that Indigenous spatial practices remain resilient, despite urban transformations.

Traditional courtyard housing (Kofar gida) persists as a dominant typology in both rural and peri-urban contexts, offering natural ventilation, privacy, and microclimatic comfort through shaded enclosures (Gidado et al., 2024; Oliver, 2020; Lawal, 2024). Sacred groves and community trees (e.g., baobab and neem) continue to serve ecological and spiritual functions, including shade provision, soil conservation, and communal gathering spaces.

These practices demonstrate an embedded knowledge system where cultural, ecological, and social needs converge in spatial design. Indigenous courtyard typologies offer a replicable model for passive cooling, reducing household energy use in Katsina by an estimated 30% compared to conventional block housing.

Colonial and Modern Disruptions

Analysis revealed that colonial planning interventions, such as grid layouts and administrative zoning, often disrupted indigenous settlement logics that emphasised organic growth, shade, and social cohesion (Prussin, 1999). Postcolonial urban development further reinforced modernist ideals, privileging wide roads, detached housing, and concrete construction that increased heat stress and marginalised Indigenous building traditions (Escobar, 2018). Participants highlighted that modern estates in Katsina fail to address climate realities, leading to higher energy consumption for cooling and a diminished sense of community. This confirms earlier studies that modern planning in Northern Nigeria often alienates residents from their cultural identity and environmental context (Kalu, Ogunnaike, & Eze, 2025).

Contemporary Design Opportunities

The thematic analysis revealed several opportunities for integrating Indigenous practices into contemporary design strategies. Three interrelated themes emerged from the study, each demonstrating how traditional knowledge can contribute to sustainable and culturally grounded urban development in Katsina.

First, cultural identity and heritage preservation emerged as a key theme. Revitalising Hausa courtyard typologies within modern housing schemes offers the potential to enhance thermal comfort while upholding socio-cultural values such as privacy and gendered spatial organisation. This approach aligns with global movements in decolonising design that emphasise re-centring local narratives and traditions within contemporary practice (Escobar, 2018).

Second, community engagement and governance underscored the enduring role of traditional leaders and artisans as custodians of Indigenous knowledge. Their inclusion in participatory co-design processes not only strengthens the legitimacy of design interventions but also fosters local ownership and contributes to long-term sustainability (Bryman, 2016).

Finally, the theme of hybridisation of vernacular and modern design illustrated how emerging projects in Katsina are successfully blending traditional courtyard typologies with modern passive-cooling materials and technologies. This hybrid approach is increasingly appealing to younger generations who seek contemporary comfort without abandoning cultural identity. Together, these themes suggest that the integration of Indigenous spatial practices provides a viable pathway toward context-sensitive and sustainable design in Northern Nigeria.

Resilient Landscape Framework and Design Strategies

The study proposes a resilient landscape framework that integrates Indigenous practices into contemporary design thinking, emphasising the interdependence of cultural, ecological, and social dimensions. Drawing on the concept of biocultural resilience (Oliver, 2020; Kalu et al., 2025), this framework positions Katsina’s landscapes as living laboratories where traditional knowledge and modern sustainability principles intersect. By reinterpreting indigenous spatial logics, such as courtyard housing typologies and communal open spaces, the framework encourages designs that are both climate-responsive and culturally grounded.

Within this broader framework, several design strategies are proposed to operationalise resilience in practice. These include the incorporation of vernacular housing principles that promote thermal comfort and privacy; the development of urban green infrastructure integrating shade trees, urban gardens, and water-harvesting systems; the creation of contextually responsive public spaces that reflect local identity; and the establishment of community-based governance structures to ensure participation, continuity, and local ownership. Together, these strategies form a holistic approach that links Indigenous wisdom with contemporary sustainability imperatives, positioning Katsina’s evolving landscapes as models of adaptive, culturally resonant resilience.

A. Vernacular-Inspired Housing and Courtyard Systems: Traditional Hausa courtyard houses (Kofar gida) offer valuable lessons for contemporary housing design (Figure 5), particularly through the reinterpretation of courtyards that integrate passive cooling strategies such as shaded atriums, earth walls, and strategically placed openings to enhance natural ventilation (Oliver, 2020; Lawal, 2024). Additionally, the adoption of hybrid materials, such as stabilised earth blocks, compressed clay, and locally sourced timber reinforced with modern techniques, can preserve thermal efficiency while enhancing structural durability. Equally important, housing layouts should incorporate indigenous socio-spatial norms, ensuring privacy for women and creating shared spaces that foster extended family interaction, thereby reflecting cultural values alongside modern functionality (Prussin, 1999).

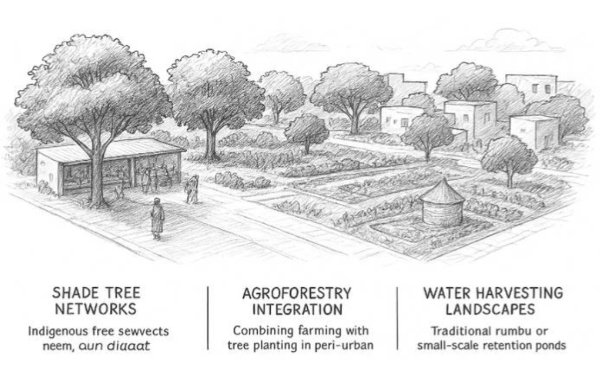

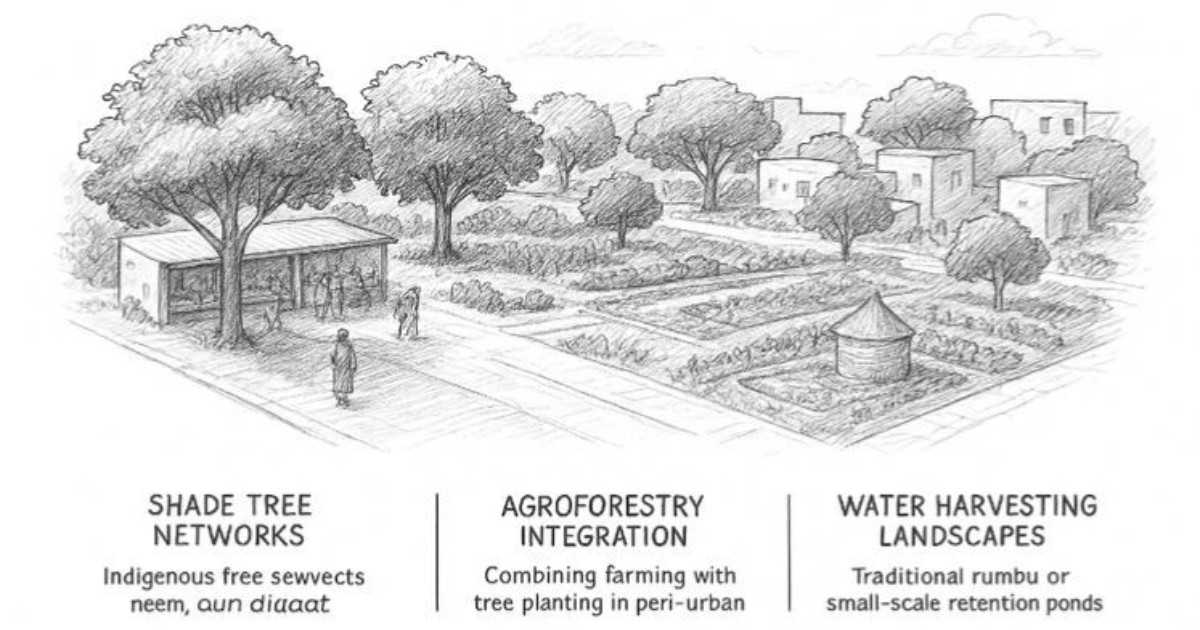

B. Urban Green Infrastructure: Sustainable landscape strategies in Katsina (Figure 6) can draw on indigenous practices by expanding shade tree networks through the planting of species such as neem (Azadirachta indica), baobab (Adansonia digitata), and tamarind (Tamarindus indica) along streets, markets, and courtyards to mitigate urban heat islands and enhance biodiversity (Bawale et al., 2025). Additionally, traditional water management techniques and small-scale retention ponds can be adapted to manage floodwater, reduce surface runoff, and recharge groundwater, thereby reinforcing climate resilience in both rural and urban contexts.

C. Public Spaces Rooted in Cultural Identity: Cultural heritage can be embedded into contemporary landscape design by protecting and reintroducing sacred groves and community trees, which historically served as gathering spaces and continue to function as both ecological assets and cultural markers (Figure 7). This approach can be complemented by redesigning market squares and open plazas to incorporate shaded seating, water features, and flexible spaces for festivals, thereby sustaining the rhythms of Hausa cultural life. Furthermore, cultural landscape corridors linking heritage sites —such as city walls, mosques, and shrines —with ecological pathways can create pedestrian-friendly routes that double as tourist attractions, reinforcing both cultural identity and environmental sustainability.

D. Community-Based Governance and Co-Design: Participatory planning that embeds traditional leaders, women, and artisans in the design process is essential to ensuring that cultural and environmental priorities are adequately reflected (Bryman, 2016). This can be supported through skill revitalisation programs that revive Indigenous construction knowledge, particularly earth-building techniques, and climate-responsive practices, thereby strengthening local capacity for sustainable development. In addition, adaptive co-governance models, such as community associations tasked with maintaining public green spaces, water systems, and heritage corridors, provide a framework for long-term stewardship that blends traditional authority with contemporary governance structures.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that integrating Indigenous spatial practices into contemporary landscape design offers a powerful pathway for fostering resilience in Katsina State, Nigeria. The framework developed highlights how traditional knowledge, when reframed and contextualized, can address present-day urban challenges such as climate change, ecological degradation, and cultural erosion.

Vernacular housing systems provide climate-responsive models that reduce energy demand; indigenous green infrastructure demonstrates sustainable water and land management; traditional public spaces reinforce cultural identity and social cohesion; and community-based governance practices foster inclusivity and ownership. Collectively, these domains illustrate that Indigenous practices are not relics of the past but dynamic, living systems that can be adapted to meet contemporary needs.

By positioning Indigenous knowledge systems at the core, the study underscores the importance of decolonizing design approaches in Northern Nigeria. This process not only preserves cultural heritage but also provides innovative, low-cost, and sustainable solutions for urban resilience.

Recommendations

Drawing from the findings and lessons of the case studies, the following recommendations are proposed to guide the integration of Indigenous spatial practices into contemporary landscape design and planning in Katsina State and beyond:

i. Mainstream Indigenous Spatial Logic into Urban and Regional Policy: Government agencies and professional planning institutions should integrate indigenous spatial patterns, such as zaure-to-courtyard sequences, shaded market typologies, and sacred groves, into state urban development frameworks. This can be achieved through local development control guidelines that promote vernacular-inspired spatial zoning, natural ventilation, and shaded public domains. Such policy integration will enhance climate responsiveness, social inclusivity, and cultural continuity in urban expansion plans.

ii. Establish Model Projects Demonstrating Hybrid Design Approaches: Pilot projects should be developed within Katsina’s new housing estates or community regeneration schemes to showcase vernacular-modern hybrids, such as courtyard housing prototypes and culturally rooted public spaces. These demonstration sites can serve as living laboratories for adaptive reuse of traditional forms, integrating passive-cooling systems, water-harvesting features, and native vegetation. Collaboration between universities, local artisans, and design professionals will enable evidence-based innovation.

iii. Promote Community-Based Governance and Co-Design Frameworks: Resilient design must be socially grounded. Local communities, especially traditional leaders, women’s groups, and artisans, should be formally included in co-design and management processes. Establishing Community Design Committees (CDCs) within neighbourhoods would encourage participatory decision-making, maintenance of public spaces, and the transmission of Indigenous knowledge systems to younger generations.

iv. Institutionalize Indigenous Knowledge in Design Education and Professional Practice: Landscape architecture and planning schools in Northern Nigeria should revise curricula to embed Indigenous ecological wisdom, courtyard typologies, and cultural landscape systems into design studios and research projects. Professional bodies such as the Society of Landscape Architects of Nigeria (SLAN) and the Nigerian Institute of Town Planners (NITP) should support continuing education workshops on decolonizing design and climate-responsive vernacular techniques.

v. Revitalize Urban Green Infrastructure Using Local Ecologies: Urban greening programs in Katsina should prioritize indigenous and drought-tolerant tree species (e.g., neem, baobab, tamarind) in streetscapes, market plazas, and courtyards to mitigate heat stress, conserve biodiversity, and restore ecosystem services. Reviving traditional water-harvesting systems, such as rumbu and retention ponds, should complement modern stormwater infrastructure to enhance resilience against floods and droughts.

vi. Protect and Reconnect Cultural Landscapes as Ecological Assets: Sacred groves, communal trees, and heritage corridors should be conserved and integrated into the broader landscape network as biocultural nodes. These areas can form part of urban ecological corridors linking mosques, historic walls, shrines, and open plazas, thus merging heritage preservation with green infrastructure.

In conclusion, the integration of Indigenous spatial practices with contemporary design strategies is not merely a cultural preservation exercise, but a practical and sustainable response to today’s urban and ecological crises. Katsina State has the potential to serve as a model for decolonized and resilient landscape design in Africa.

References

Agboola, O., & Zango, M. (2014). Review of selected features of Hausa vernacular architecture: Case study of Dakali and Zaure in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. ARTEKS: Jurnal Teknik Arsitektur, 7(3).

Bawale, S., Muazu, A., & Dankullu, M. H. (2025). Climate change and decline of cultural heritage as major causes of insecurity in Katsina State: A way forward. International Journal of Climate Conditions, 2(1), 29–34.

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.

Enwezor, O. (2019). Colonial legacies and African urban form. Journal of African Architecture and Urbanism, 12(3), 41–59.

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds. Duke University Press.

Gidado, U. M., Maulan, S., & Maimuna, S.-B. (2023). Community adaptation to climate in open spaces of the semi-arid region of Northern Nigeria. AJLA. ajlajournal.org

Gunasekaran, R., & Shanthi Priya, R. (2025). Simulating the thermal efficiency of courtyard houses: New architectural insights from the warm and humid climate of Tiruchirappalli City, India. Architecture, 5(2), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5020021

Jokilehto, J. (2020). Indigenous knowledge and cultural heritage in contemporary conservation practice. Built Heritage, 4(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43238-020-00006

Kalu, G., Ogunnaike, A. O., & Eze, W. O. (2025). Integrating biophilic and passive design strategies in Nigerian architecture: A systematic review of current practices and impacts. African Journal of Environmental Sciences and Renewable Energy, 19(1), 324–335. https://doi.org/10.62154/ajesre.2025.019.01030

Lawal, M. (2024, October 31). Climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies: Urban resilience in the face of climate change in Katsina State, Nigeria. Nigerian Association of Hydrological Sciences. https://nahs.org.ng/papers/volume-10/issue-12/volume-10-22

Mabogunje, A. (2019). Colonialism and the evolution of urban planning in West Africa. Planning Perspectives, 34(2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2018.1503648

Nwanna, C. R. (2021). Imported planning models and urban sustainability challenges in Nigeria. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 13(3), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2020.1869249

Oliver, P. (2020). Encyclopaedia of vernacular architecture of the world (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Prussin, L. (1999). African nomadic architecture: Space, place, and gender. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Gidado, U. M., Maulan, S. & Saleh-Bala, M. (2024). Indigenous knowledge in community adaptation to climate in open spaces: Semi-arid region of Northern Nigeria. African Journal of Landscape and Architectural Studies, 2(1), 45–57.

Usman, M. M., Bashir, M., Usman, H. A., El-Nafaty, A. S., Wakawa, U. B., & Abubakar, S. K. (2024). Redesigning resettlement homes for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Borno State: Integrating Kanuri cultural elements. African Journal of Environmental Sciences and Renewable Energy, 15(1), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.62154/mcfyh140

Waterson, R. (2019). The living house: An anthropology of architecture in South-East Asia (2nd ed.). Tuttle Publishing.

Zhang, M., Fang, Z., Liu, Q., & Zhang, F. (2024). Simulation and Analysis of Factors Influencing Climate Adaptability and Strategic Application in Traditional Courtyard Residences in Hot-Summer and Cold-Winter Regions: A Case Study of Xuzhou, China. Sustainability, 16(19), 8676. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198676