Re-imagining Open Spaces along the Buckingham Canal, Chennai, India

Chennai est une ville de temples depuis l'ère védique, avec des paysages naturels et culturels d'eris, de réservoirs, de canaux, de plages, de rivières, de ruisseaux et de zones humides. Malheureusement, ces paysages ont été transformés en une culture technologique de pointe, une ville dynamique de gratte-ciel, une jungle de béton d'immeubles de grande hauteur, des lumières étincelantes de la circulation, et des vies désolées et éphémères de pauvres urbains. La construction du MRTS au-dessus du canal de Buckingham a donné naissance à de nouveaux espaces ombragés mais manifestement non fonctionnels, en raison d'une mauvaise planification et d'une vision irréfléchie du gouvernement de Chennai. Ces espaces autoconstruits servent de décharge, de source d'activités illégales et de raccourci pour les usagers locaux. L'objectif de cette étude est de prêter attention à ces espaces non fonctionnels mais ombragés le long du canal de Buckingham dans la rue Elango afin de fournir des espaces verts culturels et communautaires aux citadins pauvres.

En se référant à des études de cas similaires en Inde, La présente étude a fourni des solutions d'aménagement paysager en gardant à l'esprit les besoins des habitants des bidonvilles, tels que des places vertes ombragées, des espaces pour s'asseoir, des chemins piétonniers ombragés, des espaces communautaires culturels, des aires de stationnement et des aires de jeux pour les enfants. Le système SWAB (Scientific Wetland with Activated Bio-Digester) a été utilisé pour éliminer les polluants de l'eau. Les solutions basées sur la nature ont permis de restaurer l'écosystème du canal de Buckingham. L'étude a montré qu'avec la contribution de la communauté locale et des différentes parties prenantes, ces espaces non fonctionnels peuvent être conçus de manière sensible et devenir l'identité du quartier. L'étude recommande que lors de la conception des périphéries urbaines et des infrastructures orientées vers le transport en commun, les besoins des citadins pauvres soient gardés à l'esprit et que l'autoconstruction d'espaces ouverts non fonctionnels soit évitée. La participation de la communauté est nécessaire et fructueuse lorsqu'il s'agit de traiter de tels cas dans un pays en développement comme l'Inde. Les voiesverteset les stations MRTS de Mandaveli.L'étudechercheégalement à réparer les bordsendommagés du canal enutilisant.

Chennai is a city of temple culture since the Vedic era, with naturally and culturally crafted landscapes of eris (cascading water storage tanks), tanks, canals, sea beaches, rivers, creeks, and wetlands. Unfortunately, these landforms have been transformed into a high-tech culture, a dynamic city of skyscrapers, a concrete jungle of high-rise buildings, sparkling lights of traffic, and distressed and ephemeral lives of the urban poor. The construction of the Mass Rapid Transit System (MRTS) above the Buckingham Canal gave rise to newly shaded but obviously non-functional open spaces due to improper planning and an unthoughtful vision of the Chennai government. These auto-constructed spaces act as a dumping ground, a source of illegal activities, and a shortcut for the local users. The aim of the study is to pay attention to these non-functional spaces along the Buckingham Canal in Elango Street to provide cultural and communal green spaces for the urban poor. By referring to similar case studies in India, the present study provides landscape design solutions by keeping the requirements of the slum dwellers in mind, and including shaded green plazas, seating spaces, shaded pedestrian pathways, cultural community spaces, parking areas and play areas for children. The Scientific Wetland with Activated Bio-Digester (SWAB) system has been used to remove the pollutants from the water. Nature-based solutions have been provided to restore the ecosystem of the Buckingham Canal. The study has found that, with the contribution of the local community and various stakeholders, these non-functional spaces can be sensitively designed and improve neighborhood identity. The study recommends that while designing the urban peripheries and transit-oriented infrastructures, the needs of the urban poor should be kept in mind and auto-construction of non-functional open spaces avoided. Community participation is necessary and fruitful while dealing with such cases in a developing country like India.

Introduction

Cities are continuously being altered and reconstructed, resulting in peripheral urbanisation, encroachments, auto-construction, and creation of new spaces, neighbourhoods, and marketplaces. It brings new opportunities and hopes, but at the same time, thrives on non-functional open spaces, illegal activities, criminalities, climate change, floods, pollution, and unhygienic health conditions (Caldeira, 2016). These peripheries grow slowly based on their own logic.

Eventually these peripheries often settled along low-lying areas such as the water edges of a canal, stream, large drain, or a river. Dwellers along these peripheries are classified as encroachers, offenders, polluters, and socially marginalized (Dupont & Dhanalakshmi, 2020). Presently in metropolitan cities in India, new policies, programs, real estate developments, and massive infrastructure projects for urban renewal are being set up, including special economic zones, construction of housing and IT sectors, ports, dams, mines, and transit-oriented developments. With the involvement of huge investments, poor communities are indiscriminately uprooted from their homes (Chatterji & Jenson, 2004; Coelho & Raman, 2010; IDMC, 2008; Nayak, 2008). This further leads to marginalized communities being deprived of health and education facilities, basic amenities, adequate community spaces, fresh air, and livelihood’s opportunities (Action Aid, 2004; Banerjee, 2008).

The resettlement of the urban poor further exposed them to natural calamities and frequent disasters such as floods, droughts, climate risks, famines, pollution, and unhygienic health conditions (Kaushik, 2024). The uneven resettlement of the urban poor and unthoughtful government policies and programs gave birth to non-functional open spaces in these peripheries. Yet these unused open spaces can bring hope for urban poor to live their settled yet ephemeral lives with limited natural resources and basic amenities.

The community landscape project initiated by the Delhi government, India, aimed at rejuvenating Rajokri Lake, is recognised as a pilot initiative for the restoration of 159 water bodies and providing green and healthy built environments for the community. The project employs simple and sustainable method of Scientific Wetland with Activated Bio-Digester (SWAB) system, which is highly effective in pollutant removal and also integrates environmental restoration with community engagement.

The treatment of waste and leftover open spaces through landscape solutions enhances the urban environment by providing a communal green space and promoting social learning and environmental stewardship. (Phantachang et al., 2024). Coimbatore City Municipal Corporation, in collaboration with Oasis Design Delhi, attempted to design the under-flyover space and its immediate surroundings of the Sungam bypass road flanking the southern edge of Valankulam Lake, with its 4.5 acres of unused area.

The intention of the project was to regenerate the under-flyover space and convert it into an active recreational space for the community.

The landscape design solution included a full clean-up and bund restoration, utilising shaded space under the flyover as a hub of recreational activities. The eastern verandah is an expansive area, offering sweeping vistas of the lake and the hills, with the provision of eating areas and viewpoints. The west verandah was designed as a more introspective area, fostering a self-sufficient and comfortable environment with additional activity zones for children and adolescents (NIUA, 2022).

The local residents of Govandi, Mumbai, consulted with Mumbai Environmental Social Network (MESN), a local NGO, and took up the challenge to convert a dumping ground into a quality space with community participation. This dumping ground was the hub of illegal activities, resulting in an unsafe environment for the residents. The landscape design solution included the transformation of the dumping ground into a recreational garden with an open gym area, seating spaces, and a play area for children. Diligent care provided by the locals has resulted in flourishing trees, a verdant oasis in this previously non-functional space that lacked greenery.

Individuals of all age demographics, regardless of gender, utilise the garden, experiencing a profound sense of safety. This public space has been well-maintained and has emerged as a notable landmark of the area, the neighbourhood a favourable identity (NIUA, 2022).

The aim of this research study is to address the issues and challenges of non-functional but shaded spaces under the MRTS along the edge of Buckingham Canal in Elango Street. The study refers to the Scientific Wetland with Activated Bio-Digester (SWAB) system used in the rejuvenation of Rajokri Lake, Delhi. To enhance and provide landscape design solutions for the shaded yet unused spaces under the MRTS, the study further refers to the solutions provided in the under-flyover space near the southern edge of Valankulam Lake, Coimbatore.

Landscape and Urban Transformation of Chennai City

The city of Chennai has transformed from its early beginnings in the mid-17th Century into a large mercantile and industrial metropolis, and is today one of the most culturally- and economically-significant cities in India. This growth has meant the rapid expansion of its urban limits and the corresponding transformation of the once-rural landscape into a dense, bustling and vibrant metropolis.

Despite its many attractions, Chennai has also received widespread attention for its disappearing natural habitat, poor water quality, critically-stressed aquifers, urban flooding, and consequent risks.

The many issues confronting the city can be traced back to improper planning and development. The landscape comprises natural features, such as topography, and vegetation which are jointly shaped by geological, geographical, climatic, as well as human agencies, the structure over which evolves over a period of time, such as mud flats, or estuarine marshes and mangrove forests.

Cultural features of the landscape, such as the Eri, which are small ponds built to collect rainwater, are another class of features found widely along the Coromandel coastal landscape that extend over an area of about 22,800 square km. Landforms and open spaces are clues to the vestiges of the city’s landscape structure, providing a stable image for the city with the transformation of the surrounding urban fabric.

Shifting Geographies of Buckingham Canal

The 796 km long Buckingham Canal dating back 200 years, was constructed by the British Raj as fresh water connectivity and a linkage between Kakinada in Andhra Pradesh and Chennai in Tamil Nadu (Ahmed, 2023). Earlier it was a 420 km long salt water navigation canal running parallel to the Coromandel Coast of South India from Vijayawada in Andhra Pradesh to Villupuram District in Tamil Nadu. It was a significant waterway during 19th and 20th centuries connecting most of the natural backwaters.

The Canal was built as a private transport canal for trading interests of British businessmen (Russell, 1898 and Jishamol, 2018), and reached its final length in 1897 as a famine relief project between 1876 and 1879 (Nightingale, 1879). In this phase the canal was treated as a centralised project to serve a colonial ambition both as private tolled waterway and later as a famine relief project (Nightingale, 1879 and Kaushik, 2024).

The width of the canal has been reduced in some parts from 60 to 6 metres, carrying only sewage water and garbage within the limits of Chennai and encroached on by poor households and industries owing to lack of management (Muthiah.S.1998 and Jishamol, 2018). The central Buckingham Canal is 7.1 km long and acts as a flood moderator for densely populated areas (Jishamol, 2018).

Auto-construction of Non-Functional Open Spaces

The canal was divided into several sections, each with its own unique ecological characteristics, landscapes, and uses such as tidal balance and backwater drainage, as well as different levels of upkeep, use, and repair (Russell 1898; Coelho et al. 2017). The state viewed the canal as a vacant piece of land that could be used to build urban infrastructure, becoming more disassociated from the canal's intended use for inland navigation.

In terms of this perspective, the canal is more of a land corridor that passing through the city and providing a convenient alignment for the construction of road and rail connections, than it is a waterway (MTS 1996). The canal alignment was identified in the 1980s as a tract of inexpensive open space for the Mass Rapid Transit System (MRTS), the city's elevated rail route (MTP 1996).

With the increase in the number of immigrants, housing was built close to work sites, some 10% of the city's slums being located along the banks of the Buckingham Canal (Coelho, 2022). The alignment of MRTS above the canal at some places gave rise to non-functional open spaces. Some of these unused spaces are left abandoned due to conflicts between slum dwellers and the government, and some are not in a livable condition due to unhygienic health conditions and the dumping of waste and sewage.

Study Area

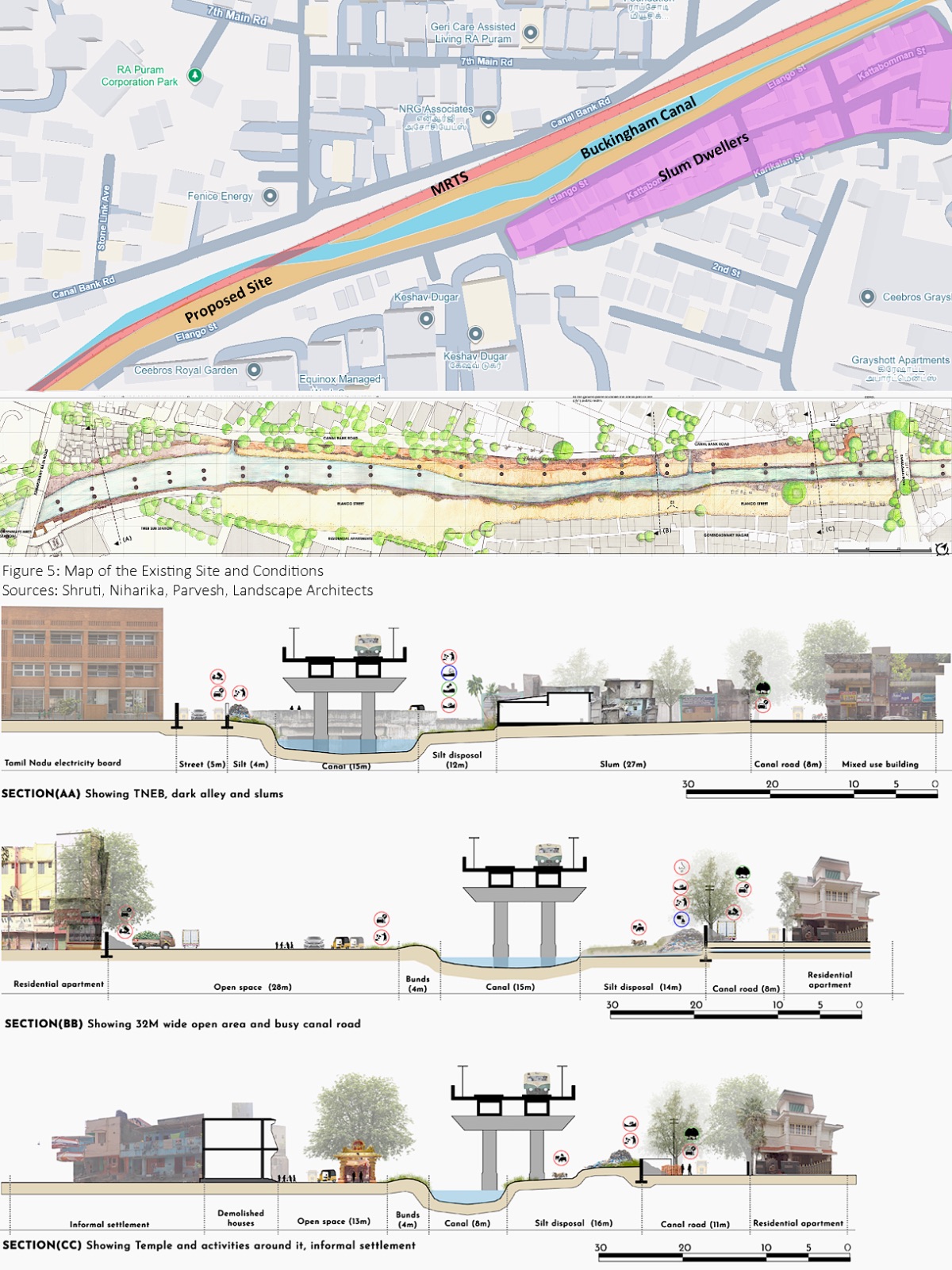

The area between MRTS stations Greenways and Mandaveli along the canal, also known as Elango Street of Govindswami Nagar has been selected as the proposed site, having been designated as a slum by the Slum Clearance Board (SCB). The proposed site acts as a shortcut to reach nearby schools, commercial areas and other residential communities, and although there is high pedestrian footfall, there are no dedicated pathways or shade, and is not safe after sunset. The site is also used for car parking, religious and cultural celebrations and fetching drinking water by slum dwellers, the site having a small temple and water storage tank near the canal.

Identification of Issues and Challenges

Despite unfavourable steps of eviction taken by SCB Chennai, the site is facing serious issues and challenges as follows:

Shrinking of the canal due to sewage and waste disposal

Erosion of water edges due to heavy rain and continuous siltation

Spread of unhygienic and serious health conditions

Increase of illegal activities after sunset

Disconnection of site from other open spaces due to demarcation boundary/compound walls

Degradation of landscape ecosystem and inaccessibility of both edges of the canal due to construction of the MRTS

Landscape Design Solutions and Proposals

Elango Street has the potential of having shaded spaces under the MRTS along the canal and a social, cultural, and ecological connection between the urban poor and other parts of Chennai city. With the collaboration of Chennai Municipal Corporation and local community participation, landscape design solutions such as rain gardens to absorb storm water, pedestrian shaded pathways for the people who use Elango Street as a shortcut, cultural gathering spaces near the temple to celebrate festivals, tree canopy plazas for seating, parking spaces for auto-rickshaws, and play areas for children have been provided.

The use of artificial lighting along the canal has been provided for safety and to avoid illegal activities. The edges of the canal have been connected by a small bridge for access to both sides. Vertical gardens have been installed on columns of the MRTS stations to reduce heat gain. These landscape design solutions have been provided by keeping in mind the requirements of the fishing community, drivers, small children and women, who fetch water from the water tanks.

Landscape Strategies and Nature Based Solutions

The width of the canal has been kept uniform by removing the waste from both sides and depth has been increased at the centre. Landscape strategies and nature-based solutions have been used to repair damaged edges of the canal from soil erosion, sewage disposal, and poor water quality. The Scientific Wetland with Activated Bio-Digester (SWAB) system has been used to remove pollutants from the water, with dense plantations of wild grasses provided on both sides to maintain the ecosystem of the canal. The use of riparian vegetation, along with phyto-remediation to purify the water. Wild grasses have been used in constructed wetlands, such as water cypress, Egyptian water grass, vetiver grass, and Job’s tears grass, to add biodiversity. The use of bioswales has been used to avoid inundation.

Conclusions

The study shows that in a developing country like India, the auto-construction of spaces on urban peripheries, water edges, rivers, large drains, and railways is very prevalent, in the absence of proper urban planning, insensitively designed neighborhoods, unthoughtful transportation infrastructure, and pressure from real estate developers. The study has attempted to provide solutions to the urban poor settled along the edges of the Buckingham Canal by restoring the ecosystem of the canal, enhancing cultural and communal green spaces, and establishing lost social, cultural, and ecological connections to bring hope for the future and their custodianship.

The study also recommends that while designing the city's infrastructures, such as transit-oriented development, waterfront development, and along the urban peripheries, government organisations, policymakers, stakeholders, and real estate developers should avoid the auto-construction of non-functional open spaces. Sensitively designed open spaces can become the lungs for any city and bring healthy environments for its citizens. To keep the city culturally and socially alive, it is important to consider the lives of the urban poor, who also play a role as service providers.

References

Basheer Ahamed, S.M.Z., 2023. Restoration of Buckingham Canal Chennai as a case study.

Caldeira, T.P., 2017. Peripheral urbanization: Autoconstruction, transversal logics, and politics in cities of the global south. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35(1), pp.3-20.

Coelho, K., 2022. Water’s Edge Urbanisms along the Buckingham Canal in Chennai. In R. Padawangi, P. Rabé, & A. Perkasa (Eds.), River Cities in Asia: Waterways in Urban Development and History 213–240. Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv31nzkv6.12

Coelho, Karen, and Nithya Raman., 2010. “Salvaging and Scapegoating: Slum Eviction on Chennai’s Waterways.” Economic and Political Weekly, 45(2): 19–23

Coelho, Karen. 2017. “The Canal and the City: An Urban-Ecological Lens on Chennai’s Growth.” India International Center Quarterly, Special Issue on The Contemporary Urban Conundrum, winter 2016–Spring 2017: 87–300.

Dupont, V. and Dhanalakshmi, R., 2020. Living on the margins of the legal city in the southern periphery of Chennai: A case of cumulative marginalities. In Living in the Margins in Mainland China, Hong Kong and India (pp. 176-194). Routledge.

Jishamol, B., 2018. Slums of Chennai around the Buckingham Canal–with special reference to Govindaswamy Nagar. Int J Curr. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Researches (IJCHSSR) ISSN: 2456-7205, Peer Reviewed J, 2(2), p.15.

Kaushik, N.S., 2024. Liquid Margins: Understanding the Shifting Nature of Marginal Geographies through the Buckingham Canal in Chennai.

Lipský, Z., 2007. Methods of Monitoring and Assessment of Changes in Land Use and Landscape Structure. Ekol. Kraj, pp.105-118.

Metropolitan Transport Project (Railways) Madras (MTP). 1996. Mass Rapid Transit System: Madras City-Phase II.

Munuswamy, A., 2011. Buckingham Canal–A Case Study. Board of Editors, p.134.

Muthiah.S. 1998. Madras Rediscovered- 2004 (A Historical Guide to Looking Around, Supplemented with Tales of Once Upon a City), Chennai: East West Books

Nightingale, F., 1879. Irrigation and Water Transit in India in Illustrated London News 74, 450.

National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA) New Delhi, 2022. Transforming Urban Landscape in India. A compendium of 75 Public Spaces

Nüsser, M., 2000. Change and Persistence: Contemporary Landscape Transformation in the Nanga Parbat Region, Northern Pakistan. Mountain Research and Development, pp.348-355

.jpg)