Outdoor Recreation Spaces in the Development of Children with Mental Disabilities

Cet article présente une proposition de conception d'une nouvelle aire de jeux inclusive au centre pour enfants de Dagoretti, visant à résoudre le problème critique de l'inadéquation et de l'inaccessibilité des espaces extérieurs et des installations de jeux pour les enfants souffrant de déficiences mentales, qui sont essentiels à leur développement physique, psychologique et social holistique. L'étude met l'accent sur le potentiel thérapeutique des espaces de loisirs en plein air dans la gestion et l'atténuation potentielle des problèmes de santé mentale chez les enfants.

L'importance de l'étude réside dans la gestion des troubles mentaux, voire leur traitement, grâce à l'utilisation intensive d'espaces de loisirs en plein air dans la thérapie des enfants souffrant de troubles mentaux. L'étude se concentre sur l'impact transformateur des environnements extérieurs inclusifs et sur l'intégration des enfants souffrant de déficiences mentales aux côtés de leurs pairs neurotypiques, en examinant les résultats immédiats et à long terme sur le développement.

Les objectifs de l'étude sont la création d'aires de jeux inclusives qui accueillent tous les enfants, quelles que soient leurs capacités mentales, et l'évaluation de la qualité physique de ces espaces et de leur rôle dans la promotion du développement social, physique et cognitif. Tout en s'inscrivant dans une discussion plus large sur le potentiel thérapeutique des espaces extérieurs pour les enfants souffrant de déficiences mentales, l'objectif principal est l'application pratique de ces idées dans le contexte spécifique de Dagoretti.

Ce projet a été entrepris dans le cadre d'une initiative de recherche étudiante du programme d'architecture paysagère de l'université d'agriculture et de technologie Jomo Kenyatta. L'étude identifie le manque critique d'installations récréatives extérieures dédiées au centre pour enfants de Dagoretti. Elle propose des interventions de conception intégrant la physiothérapie, l'ergothérapie et la thérapie par le jeu dans un environnement extérieur unifié.

L'étude souligne comment des paysages inclusifs, riches en sens et adaptatifs peuvent renforcer l'autonomie des enfants souffrant de déficiences mentales et favoriser leur développement physique, social et cognitif. Les stratégies de conception clés comprennent des sentiers naturels variés, des éléments de stimulation sensorielle, des équipements de jeu adaptés et des zones de calme, tous adaptés aux besoins spécifiques observés à Dagoretti. En reliant la théorie à la pratique, ce projet démontre comment les espaces extérieurs peuvent être transformés en paysages thérapeutiques qui contribuent de manière significative au développement de l'enfant.

This paper presents a design proposal for a new inclusive playground at the Dagoretti Children’s Centre, aimed at addressing the critical issue of inadequate and inaccessible outdoor spaces and play facilities for children with mental impairments, which are essential for their holistic physical psychological and social development. The study emphasises the therapeutic potential of outdoor recreation spaces in managing and potentially alleviating mental health challenges in children. The significance of the study is on management of the mental disorders, if not treating it, through providing intense use of outdoor recreation spaces in the therapy of mentally impaired children. The study focuses on the transformative impact of inclusive outdoor environments and integrating children with mental impairments alongside their neurotypical peers, examining both immediate and long-term developmental outcomes. The objectives of the study are for the creation of inclusive playgrounds that accommodate all children irrespective of their mental ability, and to assess the physical quality of these spaces and their role in fostering social, physical and cognitive development. While grounded in a broader discussion on the therapeutic potential of outdoor spaces for children with mental impairments, the primary focus is the practical application of these insights to the specific context of Dagoretti. This project was undertaken as part of a student research initiative in the Landscape Architecture programme at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology. The study identifies the critical lack of dedicated outdoor recreational facilities at the Dagoretti Children's Centre. It proposes design interventions integrating physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and play therapy into a unified outdoor environment. The study emphasises how inclusive, sensory-rich, and adaptive landscapes can empower children with mental impairments and foster their physical, social, and cognitive development. Key design strategies include varied natural pathways, sensory stimulation elements, adaptive play equipment, and calm zones, all tailored to the specific needs observed at Dagoretti. By connecting theory with practice, this project demonstrates how outdoor spaces can be transformed into therapeutic landscapes that contribute meaningfully to child development.

Introduction

There is an emerging body of evidence on the developmental significance of contact with nature, which strongly supports the design interventions proposed for Dagoretti Children's Centre. Research shows that natural landscapes provide multisensory experiences and opportunities for physically active, imaginative play, all of which are critical for children's physical and mental wellbeing.

Given the Centre’s existing limitations, this project applies evidence from studies (Wells & Evans, 2003; Taylor et al., 2001) to develop a customised outdoor space that promotes motor skills, cognitive function, and emotional resilience among children with mental impairments. The design further incorporates features inspired by findings from Grahn et al. (1997) and Moore & Wong (1997), adapted to the unique needs identified through on-site observation and stakeholder interviews at Dagoretti.

Adults, parents and early childhood educators, must design the outdoor play environment with equal care and attention as they pay to the indoor environments, ensuring that these opportunities are inclusive of all children.

Children with nature nearby their homes are more resistant to stress; have lower incidence of behavioral disorders, anxiety, and depression; and have a higher measure of self-worth. The greater the amount of nature exposure, the greater the benefits (Wells & Evans 2003). Spending time in nature has been shown to reduce stress and benefit treatment of numerous health conditions (Kahn, 1999). Symptoms of children with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) are relieved after contact with nature. The greener the setting, the more the relief (Taylor et al. 2001). Children with views of and contact with nature score higher on tests of concentration and self-discipline. The greener, the better the scores (Wells 2000, Grahn, et al. 1997, Taylor et al. 2002). Children who play regularly in natural environments show more advanced motor fitness, including coordination, balance and agility, and they are sick less often (Grahn, et al. 1997, Fjortoft & Sageie 2001). When children play in natural environments, their play is more diverse.

There is a higher prevalence of imaginative and creative play that fosters language and collaborative skills (Moore & Wong 1997, Taylor, et al. 1998, Fjortoft 2000). Play in a diverse natural environment reduces or eliminates bullying (Malone & Tranter 2003). Nature helps children develop powers of observation and creativity, as well as a sense of peace and being at one with the world (Crain 2001). Early experiences with the natural world have been positively linked with the development of imagination and the sense of wonder (Cobb 1977, Louv 1991). Wonder is an important motivator for lifelong learning (Wilson 1997).

Dagoretti Children's Centre

This work was initiated as part of a student-led research and design project. The Dagoretti Special School did not directly commission the study; rather, it emerged from academic coursework requirements aimed at applying landscape architectural research into real-world practice.

Through field visits, structured interviews, and observation sessions, the team identified critical gaps in existing outdoor facilities. These findings directly informed the design considerations for the new playground, ensuring that proposed interventions align closely with the daily therapeutic needs and developmental goals of the children served by the Centre. The study sample comprised 120 participants, including children with disabilities, children officers, parents, and guardians.

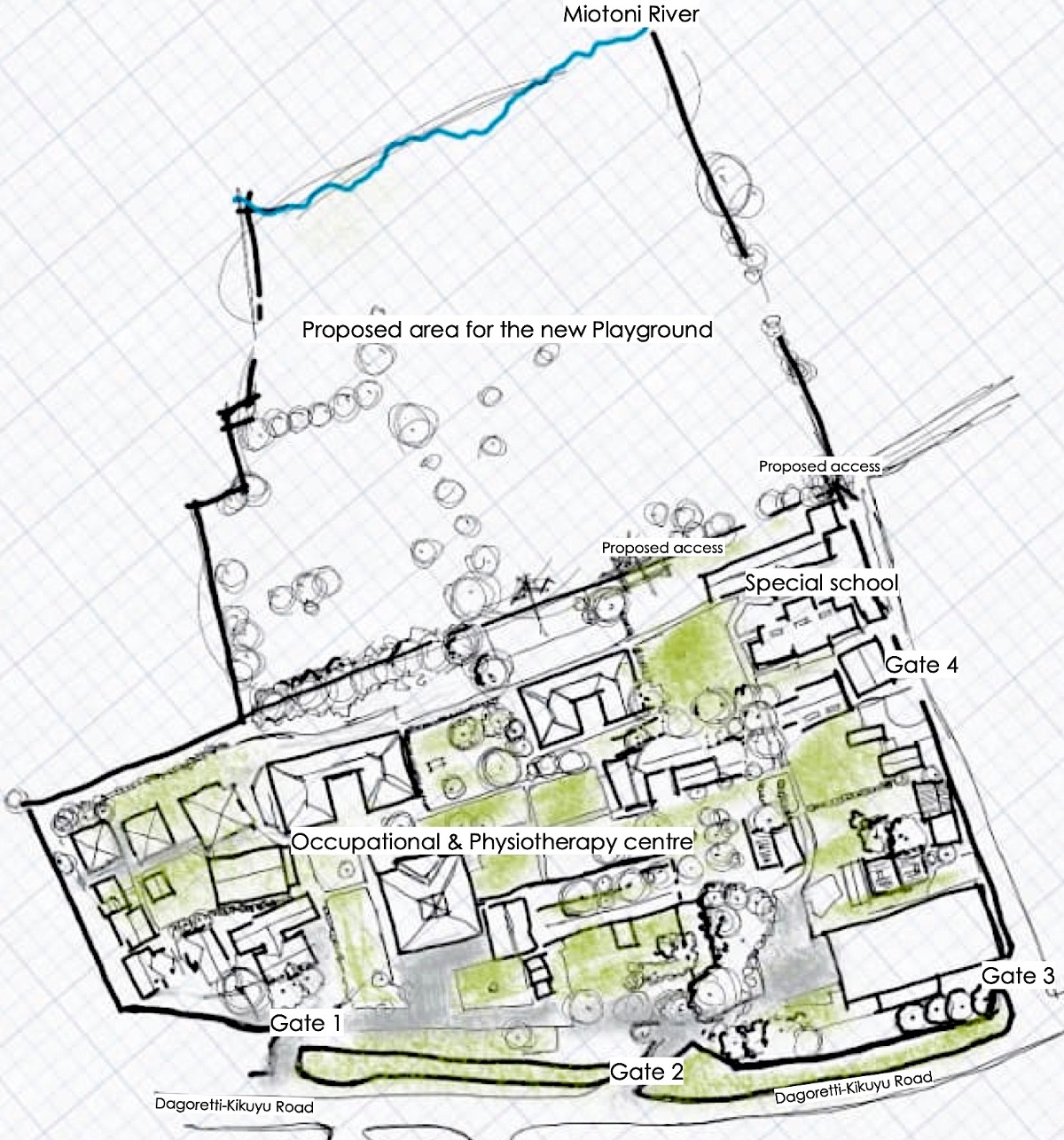

The Site

Dagoretti special school has 321 students. The institution is inclusive, with children who require therapy being transported to the adjacent institution, Dagoretti Children's Centre. The school began as a constituent institution for learning from the original centre. There were two major therapies conducted i.e. physiotherapy and occupational therapy, which was done in both outdoor and indoor environments. Physical therapy included rehabilitation of the limbs and other physical features of the body, while occupational therapy involves self-care such as grooming, toileting, dining and dressing. All therapies were incorporated as play. Specific activities which the children undertook include sand play, painting, play dough, tabletop toys, jigsaws, threading, sequencing toys and shape sorters.

Utilisation of the Outdoor Space

Despite lacking a dedicated playground and relying on open left-over spaces, the special school facilitates various outdoor activities including ball games, running, flee biers, tag of war, soft balls, and long jump. The children's centre provides therapy services to both the school and community children, though most therapy sessions occur indoors. The facility offers specialised equipment for developing hand-eye coordination and strengthening finger grip, while throwing and catching games enhance cross motor abilities.

Additionally, blowing and sucking games are employed to stimulate the oral cavity, particularly beneficial for children with drooling issues or speech difficulties. By integrating therapeutic elements into play activities, children are encouraged to expand beyond their comfort zones while enjoying the learning process.

However, the school faces significant space constraints relative to its population, serving both special school students and community members. This limitation has necessitated implementing a scheduled system where different groups are allocated specific days for therapy sessions. Furthermore, while play materials are available, questionnaire data indicates these are insufficient for the number of children served.

The study established that though there are efforts in making the outdoor recreation spaces suitable for these children, there is more that could be done to ensure that the landscape resources are utilised in order to improve the development of the mentally handicapped child. More space needs to be acquired in the neighbourhood of these institutions as the research revealed that the spaces were small compared to the number of users.

In the case of Embu school for the mentally handicapped, they have to borrow grounds from the neighbouring school, which does not have the required facilities. An improvement to the existing conditions needs to be done in order to ensure that the access and use of these outdoor recreation spaces play a therapeutic role thus contributing to the development of the mentally handicapped children.

A variety of spaces need to be provided to cater for individual needs such as those who require areas with bright colours that will build their stimulation, and those who require areas with less bright colours where these could affect them negatively. 90% of the teachers and officers who were interviewed, along with the literature review, indicate that inclusive play and learning of normal children and mentally handicapped children, helps them to live and understand each other at an early age. Since mentally handicapped children learn from adaptation, as shown in the literature review, inclusive playgrounds will help them to learn skills from normal children.

All therapies, whether occupational or physiotherapy, should be administered as play. The children are able to learn as they play.

From both the literature review and data collected, it has been established that children derive many benefits from the access and use of outdoor open spaces. Design elements of texture, sound, sight and smell can be incorporated to improve the children’s stimulation. Landscape planting provides an opportunity for horticultural therapy, helping the children to have a special connection with plants, gardening and nature to facilitate their growth, development and wellbeing.

Design Considerations: Natural Pathways and Terrain Variability

The design includes pathways that incorporate varied terrain, such as slopes, ramps, textured surfaces, and natural obstacles which significantly enhance physical therapy. These elements encourage balance, coordination, and strength-building activities. Children can engage in walking, running, and manoeuvring through diverse landscapes, all of which contribute to improving their motor skills. Engaging with natural pathways provide a safe and stimulating environment for developing core strength and agility while reducing the monotonous nature of traditional therapy settings.

Sensory Stimulation Elements

Incorporation of sensory gardens, tactile panels, and auditory features (wind chimes, water sounds) into the landscape enhances occupational therapy by facilitating sensory integration. Children can explore different textures, scents, and sounds, which can be particularly beneficial for those with sensory processing challenges. Sensory-rich environments help in developing sensory awareness skills, which are crucial for daily activities such as dressing or eating. They also encourage exploration, fostering independence while improving emotional regulation.

Inclusive Play Areas

The design includes play spaces with adaptive play equipment, which allows children to engage in activities that promote strength, flexibility, and social interaction. Equipment such as accessible swings, adaptive merry-go-rounds, and multi-sensory structures ensures that all children can participate, regardless of their abilities. This provides opportunities for social engagement and peer interaction, essential for cognitive and emotional development, while collaborative play enhances teamwork and communication skills.

Calm Zones and Reflection Areas

The design integrates serene spaces with natural elements like ponds, gardens, or quiet seating areas, to encourage children to take breaks and practice mindfulness, which are important components of emotional and psychological therapy. These calm zones also feature gentle visual and auditory elements, such as soft lighting or soothing water features. Calm zones allow children to recharge and self-regulate, making them more receptive to therapy and easing anxiety levels. Such environments can provide mental clarity, which is crucial for focusing on therapeutic tasks.

Interactive Landscaping

Climbing structures, balance beams, and small hills foster physical rehabilitation through play. This is to encourage children to navigate challenges, and improve their problem-solving skills and physical coordination. Interactive landscapes motivate children to engage in therapy through playful exploration, increasing their willingness to participate in physical activities and exercises necessary for rehabilitation.

Adaptive Seating and Gathering Spaces

Designing flexible seating areas that accommodate various therapy sessions and group activities is essential. These spaces include picnic tables for crafting activities or benches for group discussions, allowing therapists to facilitate various interactions and exercises. These spaces will encourage interaction and therefore lead to improved communication skills and social development. Providing comfortable, accessible seating reduces barriers, making it easier for all children to participate in group activities.

Visual Cues and Wayfinding Elements

Finally, colour-coded pathways and symbols are to be incorporated to assist children in navigating the space and understanding the flow of activities. These cues help to reinforce spatial awareness and direction-following skills, critical components of occupational therapy. By providing clear guidelines on where to go and what to do, children can develop greater independence and confidence. This clarity will enhance the children’s ability to follow instructions and participate actively in both physical and occupational activities.

References

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Mental Disorders and Their Characteristics. Washington, DC: AACAP, n.d.

Cobb, Edith. The Ecology of Imagination in Childhood. New York: Columbia University Press, 1977.

Crain, William. Reclaiming Childhood: Letting Children Be Children in Our Achievement-Oriented Society. New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2001.

Fjortoft, Ingunn, and J. Sageie. "The Natural Environment as a Playground for Children: Landscape Description and Analyses of a Natural Playscape." Landscape and Urban Planning 48, no. 1-2 (2000): 83-97.

Fjortoft, Ingunn. "The Natural Environment as a Playground for Children: The Impact of Outdoor Play Activities in Pre-Primary School Children." Early Childhood Education Journal 29, no. 2 (2001): 111-117.

Gesler, Wil. "Therapeutic Landscapes: Medical Issues in Light of the New Cultural Geography." Social Science & Medicine 34, no. 7 (1992): 735-746.

Grahn, Patrik, Fredrika Mårtensson, Bengt Lindblad, Peter Nilsson, and Anders Ekman. "Outdoor Environments in Childcare Centres: Results from a Swedish Investigation." Early Child Development and Care 147, no. 1 (1997): 1-28.

Hewes, Jane. Let the Children Play: Nature’s Answer to Early Learning. Early Childhood Learning Knowledge Centre, 2006.

Kahn, Peter H. The Human Relationship with Nature: Development and Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999.

Kamaldeep, Bhui. Culture and Mental Health: A Comprehensive Textbook. New York: CRC Press, 2007.

Liberty, Richard. Disability and Society: A Social Construct Approach. London: Routledge, 1994.

Louv, Richard. Childhood's Future: Listening to the American Experience. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991.

Malone, Karen, and Paul Tranter. "Children’s Environmental Learning and the Use, Design and Management of School Grounds." Children, Youth and Environments 13, no. 2 (2003): 87-137.

Moore, Robin C. Childhood’s Domain: Play and Place in Child Development. London: Croom Helm, 1996.

Moore, Robin C., and Nilda G. Wong. "Natural Learning: Creating Environments for Rediscovering Nature’s Way of Teaching." Children's Environments Quarterly 14, no. 3 (1997): 34-52.

Obaseki, Y. Intellectual Disability and Social Perception. Lagos: Heritage Press, 2009.

Oxford Medical Dictionary. Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary, 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Pyle, Robert. The Thunder Tree: Lessons from an Urban Wildland. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002.

Taylor, Andrea, Frances Kuo, and William Sullivan. "Coping with ADD: The Surprising Connection to Green Play Settings." Environment and Behavior 33, no. 1 (2001): 54-77.

Taylor, Andrea, Frances Kuo, and William Sullivan. "Views of Nature and Self-Discipline: Evidence from Inner City Children." Journal of Environmental Psychology 22, no. 1-2 (2002): 49-63.

UNESCO. Integrating the Disabled into Society: A Study on the Role of Education and Social Policy. Paris: UNESCO, 1995.

Wells, Nancy M. "At Home with Nature: Effects of ‘Greenness’ on Children's Cognitive Functioning." Environment and Behavior 32, no. 6 (2000): 775-795.

Wells, Nancy M., and Gary W. Evans. "Nearby Nature: A Buffer of Life Stress among Rural Children." Environment and Behavior 35, no. 3 (2003): 311-330.

White, Randy, and Vicki Stoecklin. Children’s Outdoor Play and Learning Environments: Returning to Nature. White Hutchinson Leisure & Learning Group, 1998.

Williams, Allison. Therapeutic Landscapes: The Dynamic between Place and Well-being. Lanham, MD: University PreMurage journal imagesss of America, 1999.

Wilson, Ruth A. Nature and Young Children: Encouraging Creative Play and Learning in Natural Environments. New York: Routledge, 1997.

.jpg)